Indonesian art, emerging from decades of the repressive Suharto regime, began to participate in large-scale international survey exhibitions that were the most marked expression of globalisation in the fine arts.

The most marked expression of globalisation in the fine arts has been the increasing number of large-scale international survey exhibitions and biennales that select and display contemporary art from all corners of the world. European and American survey exhibitions increased exponentially from the late 1980s and began to include contemporary Asian art. Similarly, in Asia, the number of survey exhibitions also increased. By the early 2000s estimates of regular contemporary survey art shows worldwide varied between 40 and 60, although the exact number of these exhibitions was difficult to determine as many changed in name or composition, or unpredictably just disappeared.[1]Rhana Devenport, Senior Project Officer at the Queensland Art Gallery, speaking at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, 19th, February 2003 for a seminar titled, The Future of Survey … Continue reading The term, ‘biennale’, in honour of the first and oldest, the Venice Biennale, became the generic term for these exhibitions whether they were held two, three or more years apart. [2]According to Marian Pastor Roces, the term ‘biennale’ or ‘biennial’ had become generic for international survey shows. For the sake of simplicity, I shall follow Pastor Roces in this use of … Continue reading

While biennales drew crowds, there was criticism and trenchant debate in art institutions and in the conferences, seminars and workshops that were associated with them. Marion Pastor Roces, art critic and independent curator from the Philippines, speaking at the Museum of Contemporary Art,

Sydney in August, 2005, referred to the affection she had for biennales while at the same time being aware of the issues. She found biennales pleasurable and seductive but considered them artificial hybrids, although she did not want to join the ‘long list of biennale bashers’, she said.

Most famous of the critics was the late British conservative art critic, Peter Fuller, when he coined the term ‘BICCA’, or ‘Biennale International Club Class Art’.[3]Reported in Studio International in relation to an article on the Guggenheim: http://www.studio-international.co.uk/reports/las_vegas_guggenheim.htm accessed 25/02/07. Club Class is the British … Continue reading Fuller felt that using the same selectors and advisors for biennales produced uniformity and all the art was beginning to look the same. Fuller had a point yet such criticism often came from that section of the art world already unsympathetic to contemporary art and who overlooked the contribution to the arts at the local level. Terry Smith stated, these critics … “fail to recognize the irony and desperation in the best of such work, ignore whole tranches of less sensational yet powerful contemporary art, and are utterly closed to the pertinence of art originating beyond the traditional centers.”[4]Terry Smith is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory at the University of Pittsburg and formerly the head of Fine Arts, Power Institute, University of Sydney. Smith, … Continue reading

By the end of the 1990s it seemed every country had at least one city that sought to raise its profile by holding a biennale of contemporary art creating ‘cultural capital for the city’, as Yahya M. Madra wrote. It also provided a profession for biennale curators, writers and administrators as well as artists. Madra, writing about the Venice Biennale of 2005, identified three main purposes for biennales:

“They serve, in part, an educational function for the local audience, for they nurture an appreciation of the “transnational standards” of aesthetic practices. It is important to emphasize, however, that it is in and through these biennales that these “transnational standards” are being set…..Second, they have become sites where the practice of the selected artists is valorized…they fulfil the economic role of the art market. Third, they contribute to the cultural “capital” of the city.”[5]Madra Yahya M., “From Imperialism to Transnational Capitalism: The Venice Biennale as a “Transitional Conjuncture”, Rethinking Marxism, Vol. 18, (No. 4) 2006, pp. 525 – 537.

In Indonesia there was a belief, often expressed by Jim Supangkat, that an institution like a Galeri Nasional or the Indonesian CP Biennale would create contacts with the international art world and develop an understanding of contemporary art in Indonesia; but, as it transpired, this did not happen smoothly. International recognition was peer review on a large scale, the equivalent of being measured against some implied standard and found worthy to participate, and it gave credibility and value to the work of those chosen that was not recognised in Indonesia until after the fall of Suharto. Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani and Heri Dono moved from the local art scene and engaged with the ‘transnational standards of aesthetic practices’ in the global art world, but not all artists and forms of art had the same opportunity. It became increasingly apparent that the same network was providing the same few artists for selection. As a result, the impact of international exhibitions was uneven in Indonesia and certain groups were bypassed.

Those Indonesian artists who prospered on the international exhibition circuit often became distanced from their home base not only physically by the requirement to be perpetually on the move, but also by developing a vocabulary of art that the local audience found difficult to appreciate.[6]Belting, Hans, “Contemporary Art and the Museum in the Global Age”, in Weibel, Peter and Buddensieg eds., 2007, Contemporary Art and the Museum, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Germany. Belting, discusses … Continue reading Apinan Poshyananda, the curator of the Traditions and Tensions exhibition, pointed out that the exhibition was never shown in the home countries of those artists in the exhibition.[7]Iola Lenzi, ed., 2001, Negotiating Home, History and Nation, Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991-2011, Singapore Art Museum, p.40. Traditions and Tensions was mounted by the Asia Society and, after opening in three venues in New York in 1996 it went on tour to Vancouver and Perth, Australia, but not to India, Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, and Thailand. Similarly, according to art writer and curator, Agung Hujatnikajennong, the works of Dadang Christanto and Heri Dono in APT/1 would have been difficult to see in Indonesia at the time.[8]Agung Hujatnikajennong, (or as given in this publication: Hujatnika) 2011, “Indonesian Contemporary Art in the International Arena: Representation and Its Changes”, in Belting, Hans, Birken, … Continue reading In many ways the local environment was not supportive of experimental, contemporary work and by the end of the 1990s only a small, albeit energetic, art world was involved in the performance, installation and new digital art forms prevalent in global exhibitions, art that the Indonesian general public found difficult to understand.

Biennales, as in all other spheres, were a product of the global technological revolution in communications, and in Indonesia the technological jump was sudden. Cemeti’s experience is an indication of the speed of change for, at the beginning of the 1990s, the gallery didn’t feel the need to possess a telephone as few in Yogyakarta had one, yet by 1996 they had their first computer. At the same time public access through Warnet or Internet cafes occurred by September in 1996 in Yogyakarta and probably two years before that in the universities, ITB and Universitas Indonesia in Jakarta.[9]Hill David T and Sen Krishna, 1997, “Wiring the Warung to Global Gateways”, Indonesia 63, 1997, p. 68. Indonesia appears to have skipped part of the telecommunications process because before the infrastructure was in place on the ground for public telephones, everyone who could afford one had a cell phone, (mobile / hand phone) and this form of communication became an essential part of life. By the early 2000s visual documentation of work in the form of photographic slides, so expensive in Indonesia, were now being provided digitally and artists could send their oeuvre and curriculum vitae by email or travel with a CD. Current information on the arts became more easily accessible, artists were mobile and the cornucopia of global art was infinitely available.

The inclusion of Indonesian artists in global exhibitions was part of a change in Western perceptions of Asian modern and contemporary art. By the end of the 1980s there were indications that the writing of theoreticians, such as Edward Said and Homi Bhabha, and Postcolonial debate generally was affecting curatorial strategies in the art centres of Europe and America. The Primitivism exhibition curated by William Rubin in 1984 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, had drawn criticism from writers and theorists for its approach to non-Western art. Thomas McEvilley considered the exhibition perpetuated the appropriation by European Modern art of non- European cultures – the common experience of colonized societies. He wrote,

“My real concern is that this exhibition shows Western egotism still as unbridled as in the centuries of colonialism and souvenirism. The Museum pretends to confront the Third World while really co-opting it and using it to consolidate Western notions of quality and superiority.”[10]Thomas McEvilley, William Rubin & Kirk Varnedoe, “Doctor lawyer indian chief, ‘primitivism’ in twentieth century art at the museum of modern art”, in Ferguson, R., Discourses : … Continue reading

In contrast the Magiciens de la Terre exhibition organized by Jean-Hubert Matin five years later in 1989 at the Georges Pompidou Centre, Paris, was considered to have moved away from this position and challenged Modernist canons of authenticity. Ethnic craft and cultural objects were no longer separated from fine art and the work of African, Oceanic and Australian indigenous artists was exhibited as contemporary art. Yet it was still non-European art being displayed to a European audience in an atmosphere of rarity and ‘magic’, and when the reverse occurred and European art was displayed to a non-European audience, it was often presented with an air of authority and an intention to instruct.

Modernist-influenced Asian art was treated as a peripheral copy of a European or American original, a pastiche rather than an interpretation. When exhibited abroad, Indonesian traditional art received considerable support but modern work was treated with less enthusiasm and often exhibited in inappropriate locations. Joseph Fischer, in his introduction to the catalogue of the first major survey exhibition of Indonesian modern art held outside Indonesia, Modern Indonesian art: three generations of tradition and change, 1945-1990, stated that of the eighty or so exhibitions of Indonesian art outside Indonesia between 1950 and 1990, most were ethnographic or traditional art, twenty-seven of which were of textiles.[11]Joseph Fischer, ed., Introduction, 1990, Modern Indonesian art: three generations of tradition and change, 1945-1990, Jakarta and New York, for Panitia Pamaran KIAS (1900-91) and the Festival of … Continue reading

This first survey exhibition of modern Indonesian art travelled to five American cities: Houston, San Diego, Oakland, Seattle and Honolulu between October 1990 and March 1992. The attitudes of the time were reflected in the difficulty organisers had in finding suitable galleries and exhibition spaces in the United States that were willing to be venues, and in two cities the works were shown in anthropological museums. According to Joseph Fischer, this was in part “a reflection in such institutions of the lack of any real experience with anything modern from Indonesia or from other Asian countries except Japan”.[12]Joseph Fischer, ed., 1990, ibid, p.12.

In 1993 the main works from this exhibition were mounted by the Gate Foundation in the Oude Kerk, Amsterdam in an exhibition titled Indonesian Modern Art.[13]The catalogue for the exhibition was Indonesische Moderne Kunst, Indonesian Modern Art, Gate Foundation, Amsterdam, 1993 The Dutch curators insisted that the paintings of the so-called Yogyakarta surrealists were facsimiles of European Surrealism and refused to exhibit the work of Agus Kamal and Ivan Sagito, saying the work would make the public laugh. The Indonesian curators argued that it was a significant local style and was one of the techniques artists used to express the repressive conditions inside Indonesia, but their arguments were rejected.[14]Marianto, Martinus Dwi, 1995, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, University of Wollongong PhD thesis, unpublished version, pp. 11 – 13. As previously mentioned, Yogyakarta surrealism is a … Continue reading

In 1994 the conference, A New Internationalism, held at the Tate Gallery in London attempted to address these prejudices. The debate centered on the relationship of the marginalized to a mainstream that was defined as Euro-American art history and institutions. Jean Fisher, editing the papers, concluded that

“… despite the increased traffic through the art institutions of cultural products by the formerly excluded, it has done little to shift the old binary opposites of Western self and other and the structures which sustain them.”[15]Jean Fisher, ed., Global Visions Towards a New Internationalism in the Visual Arts, Kala Press, London, 1994, page x.

The speakers at the conference were to become leading figures in Postcolonial, globalised art and included Rasheed Araeen, founding editor of the journal, Third Text, Hal Foster, Professor of Art History at Cornell University, Hou Hanru, Paris- based Chinese critic and curator, Geeta Kapur, Indian art historian and critic, Gerardo Mosquera, Havana-based art critic and Raiji Kuroda, curator at the Fukuoka Art Museum, Japan. They read like a roll-call of the landmark writer/curators of the new internationalism in non-European art and, by the late 1990s, they were the authorities repeatedly invited to speak at or curate non Euro- American art exhibitions. Stephanie Britton in her article concerning biennales, devised an ‘intergalactic guide to the curators of international biennials and triennials’. A ‘member of the galaxy’ was defined as having ‘a significant role as an invited curator in two or more International Biennials or Triennials’, and on this basis, for example, Hou Hanru was amongst the most stellar, having been invited eight times.[16]See “Artlink’s intergalactic guide to the curators of international biennials and triennials” in Britton, Stephanie, “Biennials of the world: myths, facts and questions”, Artlink … Continue reading

A repositioning of institutional practice influenced by postcolonial theories was underway and the concept of an Asian Modernism was developing. Significant conferences and seminars were held, among them Modernism and Post–Modernism in Asian Art, a conference organized by John Clark at the Australian National University in 1991, and Asian Modernism, Diverse Developments in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, organized by the Japan Foundation Asia Center, 1995-6. Agung Hujatnikajennong considers the Japan Foundation, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum and the Queensland Art Gallery had

“… the most ambitious agendas that eventually formed a new contemporary art cartography in the Asia-Pacific region in the ‘90s.”[17]See his summary in his paper presented at the Center for Art and Media, (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, or ZKM) in Karlsruhe, Germany 2009, … Continue reading

Australia and Japan were the intellectual brokers of Asian Modernism at this time, but the danger remained that, without local engagement in history and theory, a homogeneous definition of Asian modern art would be imposed without recognition of regional variations.[18]Modernism and Post-Modernism in Asian Art was held by the Humanities Research Centre and the Department of Art History at ANU. The papers from the conference were published in John Clark, ed., … Continue reading

Where the terms, ‘modern’ and ‘contemporary’ have been used interchangeably to mean ‘of the present’, contemporary art was now seen as different from modern art and as having superseded it.[19]See, for example, Hans Belting, 1987, The End of the History of Art, Translated by Christopher S. Wood, Chicago University Press, and Arthur Coleman Danto, 1995, After the end of art: contemporary … Continue reading Even this linear concept of contemporary art following the modern was challenged by some theorists as a ‘Euroamerican’ position which failed to make allowances for the contributions of other cultures. John Clark argues:

“… the concept of contemporary art, despite its many apparently liberal openings to the art of other cultural zones through the notions of post-modernism, post-colonialism, and globalism, is normally focused on and often explicitly derived from understanding of Euramerican art in the formal series or their negation which have unfolded since Impressionism.”[20]John Clark, abstract for his lecture, The Asian Modern, delivered at the Art Gallery of NSW, 29 March 2011.

There had been a move away from Modernist art across many cultures by the late 1980s towards an art that was involved in contemporary issues and embraced all styles and there was a concomitant rejection of purely aesthetic art. Where Modernism was understood as sequence of period styles that constituted a narrative of modern art history, now, according to theorists,

“… the great master narratives which first defined traditional art, and then modernist art, have not only come to an end, but… contemporary art no longer allows itself to be represented by master narratives at all.”[21]Arthur Coleman Danto, 1995, ibid, preface, xiii.

Contemporary art reached beyond borders to an international audience and allied with institutions, museums and exhibition structures that were not restricted by national boundaries. Hans Belting wrote,

“It therefore makes sense that contemporary art, in many cases, is understood as synonymous with global art.”[22]Belting, Hans, 2007, ibid, p.22

Yet, as many were pointing out, the pressure to enter a global dialogue was tempered by a resistance to being swamped by external cultures, and for example, societies that had been physically colonised in the past were now seeking recognition of their own identity. The homogenising tendencies of global culture were actually being undermined at the local level by the eclectic cannibalization of all sources, both local and global, which were then often used to address local issues.

Biennales provided fertile ground for the cross pollination of ideas and styles which contributed to a certain homogeneity of the art work, but they were also providing an outlet for a multitude of local characteristics and issues that were often the very criteria the selectors sought. These contradictory tendencies were hypothesized in recent forums of art debate as being characteristics of contemporary, global art. As Hans Belting wrote,

“Globalism, in fact, is almost an antithesis to universalism… [which Belting had associated with Modernism] … because it decentralizes a unified and uni-directional world view and allows for ‘multiple modernities’.”[23]Ibid.

Although globalization gave greater access to a wide range of resources and information and many new biennales appeared in the Asian region, Western institutions continued to maintain the assumption that the centre of fine art activity for the world resided in Europe and America and the model to which artwork conformed was a first world one. This model was established with the first biennale, Venice, and recognition from Western institutions continued to provide the imprimatur.

In 2006 Alain Quemin undertook an analysis to prove empirically the commonly-held assumption that the West dominated global art exchange. He used statistics of artists whose work was collected by European and American museums, was recorded in the Kunstkompass[24]Kunstkompass is a measure of artistic reputation published annually since 1970 in the German Journal, Capital. It is based on selection for exhibition, collection or publication and assumes that … Continue reading or shown in the Basel art fair and biennales. Quemin found that the most exhibited and collected artists were European and American and his statistics proved that

“… both the market and the power of institutional certification are in the hands of Western countries, particular, the richest of these countries, the US and Germany…”

He concluded:

“The richest countries may have allowed the development of biennales in the peripheral countries, but these do not really compete with the most established events, which are clearly those organised in the Western world.”[25]Alain Quemin, Professor of Sociology, l’Université de Marne-la-Vallée, “Globalization and Mixing in the Visual Arts”, International Sociology, Vol. 21, (No. 4), 2006, pp. 522-550. … Continue reading

It should be noted that Quemin himself began from the assumption that Europe and America were the centres of power by examining only their collecting policies, not those of Asian institutions.

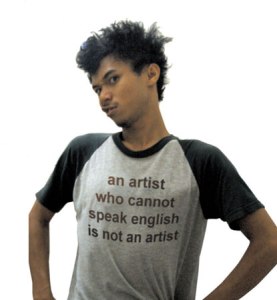

The language of international art discourse is English and if unable to speak English, participation in biennales was difficult for Indonesian artists and curators. Residencies and scholarships require a proficiency in English, even those offered by the Netherlands,[26]General scholarships in the Netherlands require a high level of English language, note the Netherlands Education Centre website. The Rijksakademie, which has provided residencies for Indonesian … Continue reading and most of the debates and papers given at international forums are in English. The pressure to speak English is illustrated by the image of an Indonesian wearing a T-shirt printed with the words, an artist who cannot speak english is not an artist. This tongue-in-cheek reference to the dominance of English introduced the English language version of the website for Indonesian Visual Art Archive, or IVAA, in 2007. The phrase was most likely appropriated from the signature work of Mladen Stilinovic, a Coatian conceptual artist who explores the social and political implications of signs and language. His word piece, An artist who cannot speak English is no artist, dates to 1992. In both cases and at different ends of the world the meaning is similar, that of marginalization outside the dominant Euro-American art dialogue. It also is an indication of the global interchange of ideas.

Biennales differed from regular group or theme shows for they were required to attract national and international audiences and meet the demands of governments and commercial sponsors who had aspirations beyond the exhibition of art. These exhibitions were expected to facilitate diplomatic and economic imperatives so they differed from commercial art fairs and similar in that their main purpose was not to sell the works from the floor. Mission statements from national, state or civic bureaucracies often expressed the dual aims of gaining status and facilitating interaction at the diplomatic and economic level.

The blueprint for biennales was the Venice Biennale for contemporary art, founded in 1895 and itself part of the incredibly popular 19th century exhibitions, expositions and world fairs that proliferated across Europe. The City of Venice chose the Biennale to be one of the ceremonies to mark the recent unification of Italy and attract tourists to finance restoration projects. These and similar reasons underlie documenta, which was established in 1955 when post World War 11 Germany was divided between East and West. Held in the town of Kassel, geographically in the middle of an undivided Germany, it was considered to be a way of reassessing German art history and the Modernism that had been rejected by the Nazi regime.

By 2000 a number of Asian cities had either initiated their own biennales or had altered their regular exhibitions of Asian contemporary art according to the biennale format, as in the case of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum.[27]The Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, FAAM, has held an Asian Art Show every 5 years since 1980 and this exhibition was converted into the Triennial in 1999. … Continue reading Junichi Shioda, chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, wrote in his catalogue essay for the Art in Southeast Asia exhibition in 1997, that the large number of exhibitions of Asian art in Japan was one of the most heatedly debated subjects in the Japanese art world. Given the number of exhibitions that he listed which were supported by the state, the Japan Foundation, or regional government, it is clear that there was also an expectation of diplomatic and commercial benefit from the artistic association of Japan with its Southeast Asian neighbors.[28]Junichi Shioda, Art in Southeast Asia Glimpses into the Future, catalogue, Tokyo, Hiroshima, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo and Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, 1997. p.153. Junichi … Continue reading The Japan Foundation, which had supported a number of these initiatives, declared in a mission statement from their President that the Foundation’s aim was to promote a ‘circle of mutual understanding’ with Japan’s neighbors. At the same time there seemed an intention to mend post war relations for, he continued, “Nor can we ignore the unresolved resentments that still linger some 60 years after the end of World War II”.[29]Kazuo Ogoura, President, The Japan Foundation November, 2005. http://www.jpf.go.jp/e/about/president.html accessed 23/04/07.

Gwangju in Korea was chosen for a biennale because the city had been the site of a demonstration for democracy in 1980 that had been brutally put down by the military regime then in power. Holding an international art exhibition there was to showcase the distinction between the now democratic South Korea and the Communist dictatorship in North Korea. Even the Asia-Pacific Triennial or APT, which claimed to be a purely cultural event, acknowledged that there were “both direct and oblique symbiotic connections between these varied interests”, that is, between culture and other national, economic and diplomatic interests.[30]Doug Hall, Director Queensland Art Gallery, Foreword, Queensland Art Gallery, The Second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, 1996, p.9 Australia was looking to participate in what was seen as an Asian economic boom and, as Melissa Chiu wrote,

“It is also no coincidence that countries best represented in all three triennials, such as China, Japan and Korea, are Australia’s major trading partners.”[31]Melissa Chiu, Museum Director for the Asia Society and Vice President, Global Art Programs, “Duplicitous Dialogue, The Asia-Pacific Triennial 1993 – 99”, Art AsiaPacific, no. 27, 2000, p. … Continue reading

There were shifting positions of power in the region, as Apinan Poshyananda wrote:

“Consequently, certain key political and economic, as well as social and cultural, structures have changed. For instance, the position of Japan and the People’s Republic of China as political and economic leaders in Asia has immense impact on art and culture in other nation-states, such as Indonesia, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Vietnam. This is evident in art and cultural exchanges designed to promote international relationships through travelling art exhibitions, concerts, acrobatic shows, food festivals, and language programs.”[32]Poshyananda, A., “Positioning Contemporary Asian Art”, Art Journal (Spring 2000), also http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0425/is_1_59/ai_63295352 accessed 16/04/07

Aki Hoashi, a Japanese arts administrator who has worked with the Japan Foundation Asia Center wrote:

“Asians very much needed to cooperate so as to make themselves visible, a theme commonly discussed in economic forums like ASEAN. But with so much historical baggage on our backs, it was not until the 1990s, particularly with the postcolonial mood so prevalent in the region, that Asian countries took serious interest in engaging with their neighbouring countries.”[33]Aki Hoashi, Director of the ARCUS project, Japan, conference paper, “Lost in Translation? – Not if you create an alternative space for exchange”, Apexart, Conference 3, Honolulu, Hawai’i, … Continue reading

Artistic exchanges became part of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations gatherings, or ASEAN and the developing ‘Asian Tiger’ economies expanded their contacts and engaged with their neighbours at such events.

The motives for Asian biennales were complicated by an aim to intellectually re position Asian modern art, seeking recognition in an ‘international forum’ that has been created and defined by Western authorities. The Gwangju Biennale mission statement declared that they sought a ‘blurring (of) distinctions between center and margin’ and to ‘break from the past of discrimination and exclusivity’ in relation to the West.[34]http://www.universes-in-universe.de/car/gwangju/english.htm accessed 26/02/07. See also the websites of the Fukuoka Triennial and Shanghai Biennale, accessed 08/07/05.

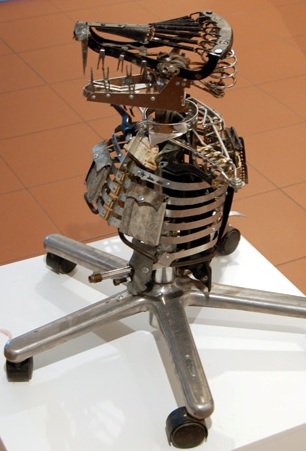

When Indonesia attempted to develop its own biennale, albeit one initiated by private interests, it was also reported in terms of gaining Western recognition. This is reflected in the title of an article in the Jakarta Post: ‘The biennale that put RI (Republik Indonesia) on the map’, the article repeating a New York Times report that said:

“… the CP Biennale 2 that put Indonesia on the map…has become a stepping stone for Indonesian contemporary artists to an international forum.”[35]“The biennale that put RI (Republik Indonesia) on the map”, Jakarta Post, Wednesday, October 12, 2005. http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2005/10/12/biennale-put-ri-map.html accessed 20/07/2012.

Yet Indonesian contemporary art was to find greater exposure in the biennales of the Asia-Pacific region than in the major centres of European and American art.

APT

The Asia-Pacific-Triennial was strategically placed in Queensland, Australia, in a Western culture geographically close to Asia. According to Paul Keating, then the Federal Treasurer, Australia was a country that had ‘its feet in Asia but its head in Europe’, a position that has, on occasion, created cultural tensions.

The Asia-Pacific Triennial was initiated by the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) and mounted in 1993, 1996 and 1999 under virtually the same team, then revisited in a different form in 2002 and approximately three-yearly since then. After 1999 Dr Caroline Turner, Deputy Director of the Queensland Art Gallery and co-founder of APT, moved to the Australian National University and QAG underwent a building expansion. APT/4 was an exhibition with fewer artists, all from the QAG collection and, as has been previously mentioned, Heri Dono was the only Indonesian artist exhibited. The focus of APT/5 in 2007 was the opening of the Gallery of Modern Art, or GoMA, a major extension of the Queensland Art Gallery.

The Asia-Pacific Triennial team undertook a meticulous process in selecting work, Indonesian artists reporting that APT had the best organisation in comparison to other biennales.[36]This was reported by Marintan Sirait amongst others, who compared the organization of APT to that of the Gwangju biennale. Interview, Marintan Sirait and Andar Manik, Bandung, 23/05/02. In Australia APT was deemed a great success for breaking new ground in the art world and for popularity with the public. Charles Green reported that not only did the state government and QAG provide significant resources but APT/1 attracted 60,000 visitors in a city with a population of just over 1 million people and APT/2 twice that number.[37]Charles Green, “Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial”, Art Journal, Vol. 58, (No. 4, 1999), p.82. APT became a benchmark, yet it too, was subject to the issues surrounding the exhibition of other cultures and, as the conference papers of APT/3 indicated, was increasingly sensitive to the debates.

By the late 1990s it was generally considered Australia’s cultural initiative in the Asian region had been lost, due in part to the continuing focus of the Australian art establishment on Euro-American art events and in part to different priorities of the conservative Federal government then in power. After 9/11 and terrorist acts in Jakarta and Bali that involved Australians, there was a change in public attitudes and official travel restrictions were imposed which curtailed curatorial research in Indonesia. Julie Ewington selected Eko Nugroho for APT/5 on the basis of seeing his work in a group exhibition in Kuala Lumpur in 2005, rather than visiting Indonesia. The Queensland State government prevented curators travelling to both Indonesian and Pakistan to make selections for APT/5 on the basis of a strict interpretation of travel warnings from the Department of Foreign Affairs.[38]Eko Nugroho, conversation, QAG, Brisbane, 02/12/06, and Julie Ewington, conversation, the Power Institute of Art, University of Sydney, 12/06/07.

FAM Asian Art Show

One of the first institutions to include the work Indonesian artists in survey exhibitions of contemporary Asian art was the Fukuoka Art Museum in Kyushu, Japan. Fukuoka mounted the first contemporary Asian Art Show in 1980 which was followed by another in 1985 and the third, in 1989. These and similar events at Fukuoka continued into the 1990s and accompanying seminars explored themes such as the influence of the West and the birth of Modern Art in Southeast Asia. In 1999 the Fukuoka Art Museum opened the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, or FAAM, and converted the Asian art shows to a Triennial.

The 3rd Fukuoka Asian Art Show in 1989 included the work of Agus Kamal, Dede Eri Supria, Ivan Sagito, Lucia Hartini, Irsam, I Gusti Nenhah Nurata, and A. D. Pirous. The majority were painters, some of whom were known as the Yogyakarta Surrealists, although, as mentioned, the use of the term, Surrealist, has been debated.[39]See the History of Asian art shows at the Fukuoka Art Museum, http://faam.city.fukuoka.lg.jp/eng/about/abt_history.html#b accessed 31/08/2011. The list of participating artists was provided by Takagi … Continue reading After 1990 the majority of work in the exhibitions was in experimental media such as installation, performance and video expressing a social and political awareness of the country the artists came from. As Raiji Kuroda, the curator of the 4th Fukuoka Asian Art Show in 1994 commented, this represented a marked change from the aesthetic interests of the modern Asian art previously exhibited in the 1980s:

“(artists)….are breaking the paradigm of ‘classic’ modern art of Asia in which most works seemed to be no more than a mixture of pre-1950s European modernism and decoration using indigenous motifs, and turning to more ‘avantgarde’ expression”[40]Raiji Kuroda, “4th Asian Art Show: Realism as an Attitude”, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka, Japan, September 10 to October 16, 1994, http://www.iias.nl/iiasn/iiasn4/ascul/realism.txt accessed … Continue reading

As with the FAM Asian Art Shows, the works by Indonesian artists selected for APT similarly reflected a transition in content and media. Nine Indonesian artists were selected for the first APT in 1993. A.D. Pirous and Srihardi Soedarsono presented abstract paintings of rich colors and surface textures, the vocabulary of international Modernist art, pleasing to the eye and without contentious subject matter. Nyoman Erawan, a Balinese artist, exhibited two dimensional and three dimensional works based on Balinese traditions. Sudjana Kerton depictions of colorful peasant activities were expressive and even witty, although his images could be interpreted as an indirect reference to the underprivileged conditions of rural life under the Suharto regime. But the paintings of Dede Eri Supria and Ivan Sagito were considerably more disturbing. Dede depicted the growth of an urban ‘concrete jungle’ in Indonesia and Ivan Sagito explored social repression as a form of psychological estrangement. It was the last three artists who, in comparison, worked with installations and performance in what Raiji Kuroda called ‘avantgarde expression’. Dadang Christanto, Heri Dono and FX Harsono specifically used their art to express sharp criticism of the Indonesian political situation and culture and this was to become the form of work that most interested the biennale selectors.

Biennale bias

Biennales tended to have certain preferences due to their size and scale and the audience they sought. Artists who explored their local politics and culture were appealing as they often included national signifiers in their work. Their work was often interpreted as ‘representing’ their country, as the cultural theorist, Jen Webb, wrote:

The national biennales and triennials, the international shows where artworks are identified by their producers and the producer/artists by their place of birth and residence: these, too, indicate the way we cling to the fantasy of the nation state as significant for artists and their work.[41]Jen Webb, “Art in a Globalised State”, in Turner, Caroline, ed., 2005, Art and Social Change, 2005, Pandanus Books, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National … Continue reading

National identity was not necessarily the original impetus for art works, yet in this, as in other aspects, selectors were catering to the expectations of their audience. Artists found themselves representing their country even when, as many argued, national identity can be a false invention either to satisfy the desired image that national powerbrokers wish to project or biennale organisers impose.

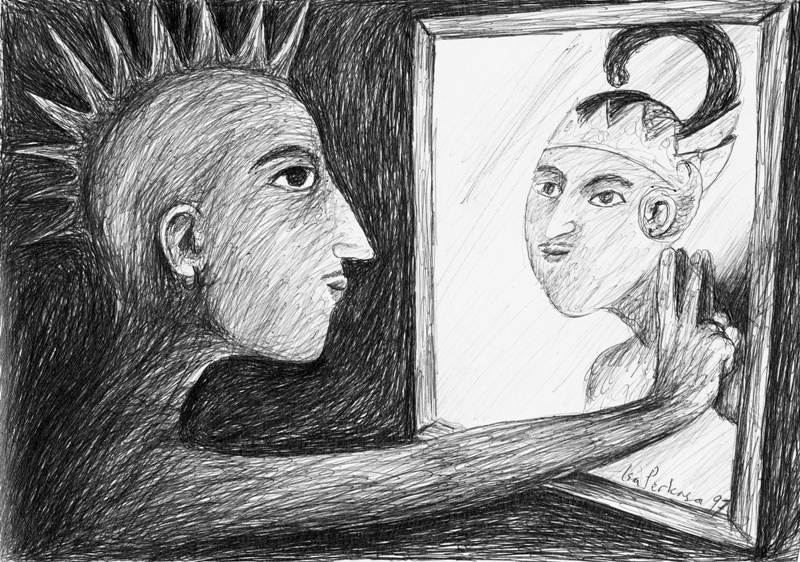

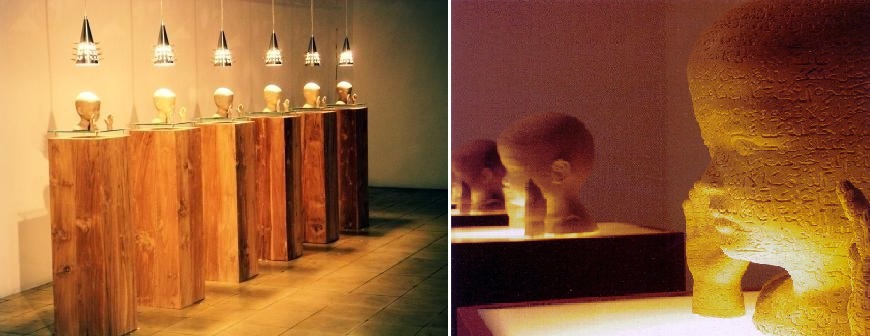

Indonesian artists were aware that overseas curators had a predilection for ‘national identity’ and art with ‘local color’. Nindityo Adipurnomo said: “They try to evaluate what is ‘Indonesian’, so they’re looking for something exotic”, an exoticism he himself could provide. This photograph, taken for the Fukuoka Asian Triennial, presents Nindityo as a symbol of Indonesia, his profile reflecting the internationally recognized national signifier of the Wayang puppet in his back pack. Yet for nearly a decade Nindityo’s art had not addressed the traditions of the Wayang but explored cultural issues through the konde or Indonesian hairpiece worn by Indonesian women as a status symbol.

Such approaches were identified in Postcolonial theory as ‘exoticizing’ or ‘othering’ – where the ‘Orient’ was perceived as a site of danger and drama. According to Ananda Poshyananda,

“The words ‘Asia’, ‘the Orient’ and ‘the East’ are loaded terms conceived by the West. Through prefabricated constructs of the imagination, Asia has become one of the West’s deepest and most recurring images of the Other.”[42]Poshyananda, A., 2000 ibid.

Christine Clark suggests that this tendency could, on occasion, produce a symbiotic response between artist and selectors:

“Does including the “Other”, the exotic, and the “ness-es” (in this case Indonesian-ness) continue to retain high currency in institutional policy?… does this propagate a trend among artists in their quest for international inclusion, to try to fit the formula?”[43]Her parenthesis. Clark, C., 2003, “When the alternative becomes the mainstream: operating globally without national infrastructure”, in Cemeti Art House, 15 years Cemeti Art House : … Continue reading

Christine Clark, Project Manager with APT

Some curators did consider that certain art was created for the purpose of participating in international events. Marian Pastor Roces, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, coined the phrase ‘Expo Art’. She did not consider that it was necessarily a negative phenomenon but felt the quality should be recognized, saying,

“… our works here are, more authentically, or more precisely: phenomena of the international exhibition/universal expo, than they are about or of, wherever it is we think we come from.”[44]Marian Pastor Roces, 2000, “Consider post Culture”, Beyond the Future, Papers from the conference of the Third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art Brisbane 10-12 September 1999, Queensland … Continue reading

The need for categories in exhibitions also reinforces national identity, most biennales organizing work by country of origin; yet alternative systems proved equally problematic. If a system based on nationality is abandoned, as when touring international curators anoint individual artists and cross borders both physically and with computer technology, the community that comprised the context of the work can be obscured. The artist enters another community, that of the international artist and art ‘star’, and the art work is distanced from the context that gave itmeaning.

Political content in art, especially from a country undergoing such radical and turbulent change as Indonesia was in the 1990s, seemed favoured by liberal-minded and sympathetic selectors and curators, hopeful that exposure through exhibition would draw attention to the issues involved. But, distanced from their original context, references could be ‘lost in translation’. Asmudjo Irianto, writing about the Pancaroba Indonesia exhibition held in 1999 at the Pacific Bridge Contemporary Southeast Asian Art gallery in Oakland, California, considered that it would not be surprising if American audiences found the subject matter difficult. He wrote:

“Most works represent a narrative of social tragedy and have many layers of other hidden meanings; they represent specific problems and particular iconographies that are unfamiliar to American audiences, and which can only be understood through a knowledge of local conditions in Indonesia – and not only of Indonesia’s social, cultural and political milieu, but also its art world.”[45]Asmudjo Jono Irianto, “An Unsettled Season, political art of Indonesia”, Art AsiaPacific, no. 28, 2000, p.83.

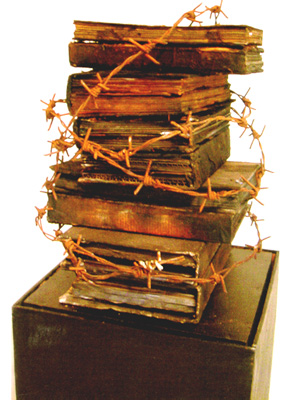

Asmudjo provided the catalogue essay for Tisna Sanjaya’s installation in APT/3 titled, The Monument of thirty-three years of Thinking with the Knee.[46]Asmudjo Irianto, “Tisna Sanjaya: The monument of thirty-three years of thinking with the knee”, in Queensland Art Gallery 1996, ibid, p.66. It was an installation that, similar to Tisna’s work in the AWAS! exhibition, was constructed from remnants of a community action and, shown out of context, required special translation. The installation included large up-side-down bamboo figures with a gun for a penis. These had been marched around Bandung to demonstrate the bullying tactics of those in power and finally strategically placed in public spaces. ‘Thinking with the knee’ is an Indonesian proverb that meant bending to another’s authority and not using your brain, that is, to be stupid; and ‘thirty-three years’ directly referred to Suharto’s years in power. The bamboo screen in the centre shows Habibie, Suharto’s nominated successor, kissing Suharto’s hand. The screen had been installed in the front garden of Tisna’s house as a political protest but both the police and local Muslim fundamentalists objected, seeing it as a criticism of Islam because the figures were wearing the peci, or the black Javanese cap that has become associated with male Muslim dress. Tisna replied that he was really criticizing corruption, but nevertheless he took the screen down.[47]Interview, Tisna Sanjaya in his home in Bandung, 04/07/2001. These histories had considerable meaning at that time and in that place, but became obscure when removed to an overseas institution, each part of the installation requiring interpretation to gain a sense of the political and cultural issues Tisna was addressing.

Biennales favoured art that made a statement and provided a spectacle – it was not a form of exhibition conducive to small gestures. According to Robert Storr, artistic director of the 2007 Venice Biennale, small and subtle works generally tend to get lost. Installations were more spectacular than two dimensional works on a wall, although paintings were not excluded. By the end of the 1990s a number of writers drew attention to the experimental and installation art in biennales, among them Melissa Chiu, who wrote in 2004 that artists working in local artistic traditions were

“… frequently overlooked by international curators interested almost exclusively in artists working in experimental media, which matched their own ideas of more progressive contemporary art.”[48]Melissa Chiu, “Asian Contemporary Art: An Introduction”, c. Oxford University Press, 2005, Grove Art Online, http://www.groveart.com/grove-owned/art/asiancontintro.html accessed 30/04/07.

The term, ‘installation,’ previously used in museum exhibition, came into common use in Western art in the 1970s and by the 1980s certain artists had begun to specialise in this kind of work, creating the genre of ‘Installation art’. Although there are varying definitions of installation art, mixed and ephemeral media is commonly used and the work is often site – specific. Professor Tatehata Akira, speaking in a symposium for the Japan Foundation Asia Center, considered that

“… installations are generally thought to be ‘temporary structures with architectural scale’.”[49]Professor Tatehata Akira, 1998, Japan Foundation Asia Center, Symposium, “Asian Contemporary Art Reconsidered”, Tokyo, Japan Foundation Asia Center, pp.170 – 173.

Installation art with its scale, display and impermanence is also less likely to appeal to the commercial art market.

In 1995 Julie Ewington considered that

“Installation is the international artistic currency of the present [that was] made available through expanded global communications and travel.”[50]Ewington, J., 1995 “Five elements, An abbreviated account of installation art in South East Asia”, Art and Asia Pacific, Vol 2, p.113

It provided an opportunity for community action in response to repressive social and political conditions and stood in opposition to the dominant styles of conservative modern art. Current writing disputes that Western influence was the sole source of Asian installation art, suggesting that it arose naturally out of local traditions of religious festivals and processions. Tatehata and Ewington both consider that the two elements, Asian custom and Western influence, possibly operated together.[51]Caroline Turner, “Indonesia: Art, freedom, human rights and engagement with the West”, in Turner Caroline, ed. 2005, ibid, p. 206 and Tatehata Akira, 1998, ibid, p. 171. Ewington wrote:

“Standard accounts suggest installation originated in Europe and America, from collage, assemblage and the Environments of the 1960s, a post- modernist response to the orthodoxies of twentieth-century life. Now another powerful narrative insists that a far older lineage exists in the temples, shrines and customary observances of South-East Asia. Neither story is the entire truth.”[52]Ewington, J., 1995, ibid, p.110

Artists became aware of the international preference for installations, Agus Suwage recommending to his wife, Tita, that she should not make ceramic works “because it will be difficult to be recognised in an international context”.[53]Titarubi in a group discussion at Benda Gallery, 27/5/02.) Pastor Roces reported that “…artists from the Philippines who were committed to painting for most of their careers until they were … Continue reading

Collaborative installations had been used by Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru as early as the 1970s and they tapped into traditions of performance and ritual in their projects. A high proportion of the Indonesian artists selected for international exhibitions in the 1990s also included performative elements with their installations, Heri Dono, Dadang Christanto and Arahmaiani among them, and physically involved themselves in their work. Given the close association of all the traditional arts in Indonesia, the relationship between performance and ceremony, for example, it is arguable that installation art was an indigenous art form that naturally engaged with contemporary Western influences. In the home environment it constituted an artistic weapon against the art practices of the establishment and the preference for paintings as decoration and investment. On the international exhibition circuit, it was a portable art form that could be reconstructed in different combinations and enter the international discourse of contemporary art.

The Indonesian perspective

By 1990 globalization in Indonesia had already resulted in an invasion of media and the collapse of the local film industry, its energies being absorbed into television, particularly in the making of the popular soap operas known as Sinetron. Where popular culture was concerned, by 2000 half the television programs, music on radio stations, books and magazines were imported.[54]Sen, K. and. Hill, D., 2000, Media, culture, and politics in Indonesia, Melbourne, New York, Oxford University Press, p.137 and p.13 Many aspects of popular culture were incorporated into contemporary fine art which escalated with the influx of comics, computer games and Internet access.

Globalization meant unrestricted access to information, current exhibitions and interesting work for visual artists, but it also meant unrestricted invasion of commercial interests, the influence of new power structures on careers and a feared loss of national and cultural identity through what was called ‘Americanization’. Arjun Appadurai considered that the dominance of America was questionable as other dynamics were in play in the local metropolitan centers. He cited the popularity in Indonesia of Japanese comics and pop music and the enthusiasm for the Japanese ‘soap’, Oshin in the 1980s, which was watched by an estimated 65% of the Indonesian population. Its success was attributed to its ‘Asianness’ in that it displayed supposedly Asian qualities of diligence and patriotism to achieve social progress. But those who were ‘invaded’ could culturally invade another and, as Appadurai continued:

“For the people of Irian Jaya, Indonesianization may be more worrisome than Americanization…”[55]Appadurai, Arjun, Modernity at Large: Cultural dimensions of globalization, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996, p.32

Clearly cultural invasion was not entirely from the West, but such simplistic demonizing of other cultures is common and it combined with the commonly-voiced perception that Western and Islamic cultures, of which Indonesia was considered a part, were in diverging cultural blocs. Islamic globalization and increased influence from the Middle East was impacting Indonesia and there was pressure from Islamic organisations in social and political life to identify as Muslim. This was reflected in increased funding for the Islamic schooling sector, attendance at mosques, the pilgrimage to Mecca and the wearing of the jilbab or headscarf by women.[56]Sally White, “Gender and Family”, in Fealy, G. and V. M. Hooker, Voices of Islam in Southeast Asia : a contemporary sourcebook, Pasir Panjang, Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, … Continue reading

At the same time there was an increasingly paranoid perception of Islam held by the West after the attack on the twin towers in New York on September 11th, 2001. This was illustrated by Arahmaiani’s experience transiting Los Angeles airport en route to Canada. On the 11th June, 2002, Arahmaiani was arrested by immigration for failing to have a transit visa, interrogated for four hours and eventually held overnight under observation by a male officer in her hotel room. Arahmaiani was deeply shocked by the experience – that she was perceived as a threat for just being Indonesian and a Muslima, and then having to share a private space with a male who must have been aware of difficulty of her position, being of a Pakistani background himself. She was outraged by the stigmatization of Indonesians and all Muslims as terrorists and as a result created a work based on the experience for a satellite exhibition of Indonesian artists at the Venice Biennale in 2003.

She reconstructed the room in which she had been held, using a color scheme of red and white, the colors of the Indonesian flag. The design of red hearts over the bedspread and curtain were romantic and sentimental and at odds with being forcibly detained and observed in that space. The intention was to send conflicting messages with the objects: the Qur’an with a bra and stockings, – the religious book beside intimate items of female clothing; a Coca Cola machine and bathroom toiletries suggesting capitalism and consumerism beside personal cleanliness. She was attempting to publicize this offensive personal experience and to raise awareness of the rising tide of anti Islamic paranoia.

Indonesian artists, along with most of their Southeast Asian counterparts, had really only begun to be selected for big international survey shows in the 1990s. Until relatively recent times the Venice Biennale has been almost entirely Eurocentric in its selection of work, and of those countries allowed to build their own art pavilions in the Giardini, the Venetian public gardens, the majority are still European. Likewise documenta has exhibited little non-European or Latin American art until very recently, and in both cases the Asian art when exhibited was likely to be Chinese.

Prior to Heri Dono, Affandi was one of the few Indonesian artists who was internationally – recognized. He was also the only artist before Heri to be invited to the Venice Biennale where he was awarded a prize in 1954. Indonesian artists had participated occasionally in the Venice Biennale through satellite exhibitions in the city but, although satellite exhibitions can be significant, it was not as prestigious as being invited to exhibit in the main, curated exhibition.[57]Satellite exhibitions are normally mounted by countries without pavilions in the Giadini to display their own artists. Indonesian artists in satellite exhibitions have included: Dewa Putu Mokoh from … Continue reading Heri Dono’s invitation in 2003 was a rare event – a swallow that did not a summer make.

The satellite exhibitions were mostly privately sponsored with minimal if any assistance from the Indonesian government. In 2003 it was assumed that the Indonesian satellite exhibition being mounted at the same time as Heri was exhibiting in the pavilion of invitees was government sponsored and coordinated. But the Indonesian artists had to shift for themselves and were self- funded or forced to organize their own sponsorship. According to the Indonesian curator, Amir Sidharta, the Indonesian Ministry of Tourism and Culture was enthusiastic when approached and agreed to provide the airfares for exhibiting artists, but somehow the money ‘disappeared’.[58]Emmy Fitri, “Artists say they were left high and dry for Venice event”, in Jakarta Post, June 1 2003. http://www.thejakartapost.com/Archives/ArchivesDet2.asp?FileID=20030601.Q01 accessed 28/02/07. Some artists then dropped out, including Dadang Christanto and Mella Jaarsma, and only those artists who could finance themselves went to Venice. Arahmaiani, for example, was funded by the gallery that represented her in Berlin at the time, Ochs and Preuss))

Although the first Biennale in Sydney in 1973 exhibited the works of nine Asian countries, this remained exceptional in its history. The Sydney Biennale has primarily addressed the relationship of Australian art to that of Europe and America. Although by 1993 with the 9th biennale it was recognized that a more ‘multicultural approach’ was necessary, the artistic director, Anthony Bond, stated,

Although I hope, through the exhibition, to provide many different perspectives on cultural practices, I still find it necessary to accept the discourse of mainstream Western culture as the field within which I operate, or from where I start.[59]Anthony Bond, “Notes on the Catalogue and Exhibition”, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Ivan Dougherty Gallery, et al., The Boundary rider : 9th Biennale of Sydney, 15 December 1992-14 March 1993, … Continue reading

If Asian art was included in the Sydney Biennale, it was likely to be from Japan, Australia’s most important trading partner for many years. Over 14 years Australia’s nearest neighbours were exhibited in the Sydney Biennale remarkably rarely: Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and India only once, Thailand and the Philippines three times and Indonesia twice.[60]See the history of the Sydney Biennale: http://www.biennaleofsydney.com.au/Biennale2004/about_us/history.html accessed 26/7/05 Affandi was again the chosen Indonesian artist in the first exhibition in 1973 and then it was not until 1996 that the work of Heri Dono and the batik studio, Brahma Tirta Sari, was shown. By 2000 the change in global perspectives began to influence the Sydney Biennale and the Biennale of 2004 was accompanied by an official parallel event mounted by Gallery 4A titled, Asian Traffic. Fifteen Asian-Australian artists were brought together with fifteen Asian artists, including Mella Jaarsma and Arahmaiani.[61]Asian Traffic catalogue published on line, 2010: http://www.4a.com.au/4a/RegistrationSrv?action=getChaps&catid=7

The long established Latin American biennales, amongst them the Bienal of Sao Paulo founded in 1951 in Brazil, had as their primary aim to make the marginalized Latin American cultures visible to Europe and America and disrupt their Eurocentrism.[62]Webpage, “Universalis: Reflecting on and innovating the manner of showing art”, by Edmar Cid Ferreira, for the XX111 Bienal Internacional de Sao Paulo: … Continue reading In both the case of the Havana Biennale and the Bienal of Sao Paulo it was not until the mid to late 1990s that Indonesian artists were selected to exhibit with any regularity and then the same artists commonly appeared in both.[63]Note appendix. The statistics for the Havana Biennale remain incomplete, as the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, Havana, Cuba, after responding to a request for information, did … Continue reading

Selection Process

The selection of work for exhibition is subject to different curatorial models. The first is that of the single director or chief curator travelling for as long as time and money allow, visiting as many artists and seeing as much work as possible – and this remains the model for the Venice Biennale. Increasingly through the 1990s local advisors were sought in each country. APT/2 in particular favored the model of co-curatorship: as Professor David Williams said, they were “concerned not to do a central authoritarian selection but consult with locals”.[64]Interview, Professor David Williams, Canberra, 06/02/04. Williams has been involved with all three APTs in the 1990s and was on the selection team for APT/1 in 1992. The selection team that visited … Continue reading

Time and finance is always a constraint and a visiting curator would be lucky to have three weeks on the ground in any one country.[65]Interview, 12/7/05, Nick Waterlow, artistic director, Biennale of Sydney, 1979 and 1986 The Southeast Asia regional team for APT/3 had 5 months, from March to July 1998, to select artists which, in comparison to other biennale selections, was remarkable. Yet in that time they had to visit the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam, as well as Indonesia.[66]Rhana Devenport, “The APT3 curatorial process: Negotiating cultural moments,” in Queensland Art Gallery, Beyond the future : the third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, South … Continue reading APT/3, in making one of the most concerted attempts to involve regional curators in the selection process, invited curators to Brisbane. Caroline Turner wrote in her introduction to APT/3

“… the aims and the curatorial philosophy of co-curatorship (is) based on equality and mutual respect between Australian, Asian and Pacific art professionals.”[67]Caroline Turner, 1999, “Journey without maps: The Asia Pacific Triennial”, ibid., p.21. Note also Melissa Chiu’s discussion of the relationship between Asian and Australian curators in Melissa … Continue reading

This approach assumes equality of training, experience and power between the regional curators which was not necessarily so. As has been previously mentioned, not one of the Indonesian curators had curatorial qualifications and until recently, most were self-taught. Therefore, despite Turner’s assertions of equality, APT was open to the criticism of having a privileged position in relation to regional dialogue and exchange.[68]See Francis Maravillas, “Cartographies of the Future: the Asia-Pacific Triennials and the Curatorial Imaginary” in Clark, J., et al eds., 2006, Eye of the Beholder, ibid., … Continue reading

To begin with, lacking connections or knowledge about art infrastructure in Asia, international selectors worked with the ‘governmental organizations’ in each country. This was reported both by Takagi Nozomi of the Fukuoka Art Museum and Caroline Turner, who said “…the art schools in Java were the first point of contact.” Later, having researched and established networks, they worked with local ‘coordinators in each country’, which was, in Indonesia, the alternative art network.[69]Email, Takagi Nozomi, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, 26/07/05 As Turner reported,

“Private galleries such as Cemeti Art House…. were a beacon for foreign collectors wanting the see the work of contemporary Indonesian artists.”[70]Turner, Caroline, ed., 2005, Art and Social Change, ibid, p. 205

The final selection always remained in the hands of the exhibiting institution, as the Fukuoka Art Museum confirmed

“The short-listed artists are then screened by the Selection Committee consisting of five academics from in and around Japan.”

For many other biennale selection committees there was a common tendency to ‘curate through catalogues’ and beat similar paths and, given the constraints of time, this was often unavoidable. Curating through catalogues compounded the selection of the same people, for only those who had already exhibited, had been published in catalogues and with a profile would come to notice. Christine Clark wrote:

This occurrence of “curating through catalogues” is primarily due to inadequate, or in some cases nonexistent, fieldwork. Often curators who purport to be globally informed are working from inadequate knowledge bases in contemporary art practices and discourses in Indonesia and its region.[71]Christine Clark, Cemeti Art House, 2003 ibid., p. 123.

Internal networks

The Australian artist, Damon Moon, co-curator of the Cemeti Foundation travelling exhibition, AWAS! observed the visiting international curator from the ground in Indonesia. Moon reported:

An Indonesian artist I know once described a certain Australian curator to me as an angel because she seemed to live in the air, only to touch down briefly at which times she was capable of performing miracles – at least for one’s career.[72]Damon Moon, “Guess who’s Coming to Dinner? Some Observations on Trans-cultural Curation”, in Hugh O’Neill and Tim Lindsey, eds., AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia, Indonesia Arts Society, … Continue reading

Artists became cynical about the selection process for international exhibitions, sometimes expressing it in their work, as Samuel Indratma did with his drawings and Agung Kuniawan with his installation, Souvenirs from the Third World, in the AWAS! exhibition. Samuel Indratma described visiting curators as making “….their trip like window-shopping, without having to grasp the actual condition”.[73]Conversation between Samuel Indratma and Agung Hujatnikajennong, 05/17/2009, reported in Agung Hujatnikajennong, 2011, “Indonesian Contemporary Art in the International Arena: Representation and … Continue reading

The curatorial procedures, as Moon indicates in his essay, were ‘traversing some very sensitive territory’, and he reflected upon ‘the notion of the visiting curator as a cultural powerbroker whose role:

“..is made significantly more complex by taking into account the role local structures play. If the visiting curator selects then the selection is both modified and to some extent controlled by this local curatorial structure. The danger lies in this nexus becoming a dependency and then ossifying. It must always be recognised that, no matter how powerful, appropriate and indeed helpful the intervention of a particular network may be, it is only one view and its dominance is increased with every interaction of this kind that occurs.”[74]Moon, Damon, 1999, ibid, pp.11-15

As Moon observed, like-minded curators reinforced each other’s taste, compounding the power of the network. Indonesia was, therefore, represented by the alternative contemporary art of Java and art-school trained artists rather than other Indonesian ethnic groups or practices. Networking, always important, is particularly crucial in Indonesia as personal referral is built into social and professional structures, and the starting point was always Jim Supangkat who operated mainly from Jakarta and Bandung. By the late 1990s, he was directing international visitors to a younger generation of curators in Bandung, the writers and lecturers associated with ITB, Rizki Zaelani and Asmudjo Irianto, and they in turn designated Agung Hujatnikajennong. In Yogyakarta, the Cemeti Art House and Foundation provided information, efficient organization and contacts, offering art that was “both recognizable and accessible to an international art audience and to those charged with the responsibility of selection”, according to Damon Moon.[75]Ibid.

The alternative to the Supangkat – Cemeti circuit was limited. Curators and theoreticians associated with the Indonesian art academies were constrained by bureaucratic objectives and were considered to be conservative and lacking contemporary theoretical knowledge. Despite the best efforts of some government bureaucrats, such as Dr. Edi Sedyawati, the General Director of the Ministry of Education and Culture who had been supportive of a number of art projects, those few state-funded art or museum administrators were tied by the requirement to serve national political agendas.[76]The background of Dr Edi Sedyawati, as a professor of Indonesian classical archaeology, indicated that the primary focus of the Ministry of Education and Culture was in the traditional arts. Their exhibitions tended to avoid contentious material and select neutral subjects for artistic themes, such as ‘Friendship and Fraternity’ or ‘Unity in Diversity’ (the Indonesian state motto, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika). Apinan Poshyananda, writing about Asian arts infrastructures generally, could have been speaking for Indonesia specifically when he wrote,

“Some art museums and institutions in the region are regarded primarily as vehicles to serve nationalist political agendas. For example, some museum curators are expected to address criteria such as national identity and indigenousness. In some cases, their positions are restricted to the role of behind-the-scene organisers, and in others they are closely attached to the government and even have to play the role of quasi-government officers. They work directly under chief curators or art directors, who in turn are obliged to pay close attention to the prevailing political climate. Several museums restrict subjects that might be sensitive or inflammatory to religious sects, national security, and ethnicity. Like it or not, these curators often have to deal with censorship in order to avoid public outcry or harsh reaction from those in power.”[77]Poshyananda, A., 2000, ibid.

Some independent curators, among them Hendro Wiyanto and Rifky Effendy, while they were recognised at home, did not gain similar recognition from international institutions. Other curators became involved in the heated art market as advisors to investors and auction houses. Overall, with the number of art curators being small and the government arts infrastructure minimal, the Supangkat–Cemeti circuit became the de facto arts infrastructure relied upon by international curators. Supangkat, Mella and Nindityo were familiar with international criteria, they were multi lingual and professional and, as Christine Clark reported, Mella knew how to organize the shipping of artworks and manage all the details for customs: crucial systems for curators.[78]Interview, Christine Clark, Canberra, 9/10/02 Most catalogues for exhibitions of contemporary Indonesian art, from Joseph Fischer’s Modern Indonesian Art in 1990, Apinan Poshyananda’s Traditions and Tensions in 1996 and the catalogues for the APTs gave credit to Supangkat and Cemeti for their assistance.

Artists’ experience

For those selected for international exhibition, the personal experience and effect on their careers could be overwhelming. Some young artists found their first overseas travel disorienting, and while Agus Suwage discovered Australian Chinese food and said he could eat Peking Duck forever, Asmudjo Irianto missed familiar elements of home and friends joked that they would have to pack a survival kit including Beef Rendang for him to take to New York. Artists were exposed to new contacts and galleries offered to promote them and sell their works – Heri Dono and Dadang Christanto are represented by Sherman Galleries in Sydney and Arahmaiani, as mentioned, by a notable Berlin gallery. Work was sold at international prices that, with the exchange rate into rupiah, made them comparatively wealthy at home. Mella and Nindityo built a new gallery with the proceeds from the sale of their works to the Queensland Art Gallery.

Invitations to international biennales exposed artists to the international debates and contacts with other art and artists. Julie Ewington referred to “…artists influencing each other and exchanging ideas with Japanese and Australian artists, and are continuing those correspondences”.[79]Ewington, J., 1995 “Five elements”, ibid,p.115. New influences could be absorbed into their work. In Arahmaiani’s case the performance artist, Marina Abramovic was a strong influence, and with Agus Suwage, who made appropriation a feature of his work, the Thai artist, Chatchai Puipia. Suwage confirmed he had met Puipia, “Yes, I know him, we have exhibited together, in Queensland, two times in Japan and in Mexico”.[80]Interview, Agus Suwage, in his home, Yogyakarta, 16/07/01

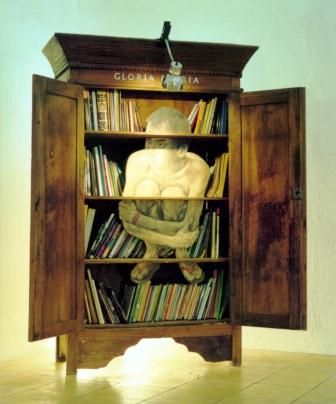

Suwage has a Postmodern attitude to appropriation, he takes from any and every source, not only from contacts made in attending international exhibitions, and has developed a distinctive body of work by applying the appropriations to himself. In 2000 he exhibited a work in the Gwangju Biennale called, The Educated Parasite which depicted him trapped in a cupboard stuffed with books. On that occasion he said the books were, “Pancacila, agama, all the things you have to study at school,” (Pancasila, the five principles of the Republic, and Agama, religion, were core subjects in all courses studied in Indonesia). In his exhibition later at Cemeti in 2001 titled, Beautify, he loaded the shelves with books about art and classical Western music. He is swamped by information from the West, he says, and he can get everything from books or the Internet, but sometimes it is too much. “I am a parasite, the artist is a parasite; I get my ideas from anything. If you want to be an intellectual you are trapped in it.”[81]Ibid.

John Clark wrote: “The fact that so much contemporary art now emerges from or stylistically resonates with other international artworks which many audiences, and perhaps some curators, might not have seen, now means it is essential for artists to make clear their references or associations..”[82]Clark, J., “Three Recent Biennales in Asia”, Art and Australia No 3, Autumn 2005, p. 390 Generally, both in theory and in practice, such artistic hybridization remains problematic. Suwage has been increasingly criticized for copying, for although originality in a work of art has been challenged by Postmodern theory, it is still perceived as a valuable commodity on the art market.

Artists required skills, contacts and organizing abilities to exhibit internationally and Jim Supangkat considered that Indonesian artists also needed assistance in making submissions. Nindityo is one of the few artists experienced in addressing a curatorial brief when making a submission. He was the only Indonesian artist selected for the Fukuoka Triennial in 2002 because he alone addressed the brief of ‘collaboration’ and submitted a work that had involved the participation of local Indonesian craftsmen. Supangkat said he could not advise other artists with their submissions in 2002 as he was a commissioner on the curatorial board of the triennial.[83]Phone conversation with Supangkat, Bandung, 20/05/02.

Nindityo made the pressures of international exhibition the subject of a work that he begun when on a residency in Cardiff, Wales, in 1999 and which became Who shall wheel me around? shown in AWAS! He portrayed himself in three versions of his own head pushing up through an aeroplane made of rattan on a cart. Each head represents a different role in his life, as indicated by the words tattooed into the face with the same hot needle technique used by Wayang puppet makers inserting patterns into the leather figures. The first head had such words as ‘corruption’, ‘nepotism’, and ‘revolution’ punched into it, the interests of a political activist; the second head reflected the interests of the artist with ‘exhibition’ and ‘biennales’ and the third reflected the issues of ‘globalization’, ‘gender’ and ‘curating’. The artist, Nindityo seemed to be saying, is pushed and pulled between these numerous and conflicting demands.

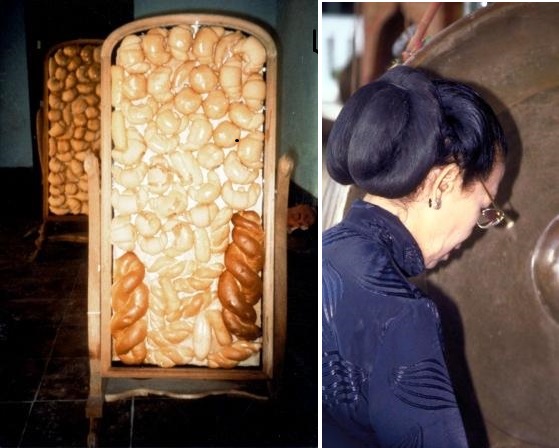

Nindityo’s participation in the 1997 Havana Biennale is an indication of how beneficial contacts and experience could be, and yet how problematic. The Indonesian government provided the airfares and the English Language newspaper, the Jakarta Post, financed the transportation of hismaterials to the exhibition in return for some of his paintings. Even so Nindityo had to abandon the work rather than collect it once returned because the Havana artsadministration sent it to the wrong address and the tax charged was more than the piece was worth to recover. His installation was titled Rono Goyang for the Hidden Ritual, or Unstable Partition for the Hidden Ritual, a work that continued his exploration of the konde, or Javanese hairpiece. He was ambivalent about Javanese tradition and ritual as symbolized by the konde, tradition he described as a burden, and had been reconstructing the konde as a fetish object in a variety of media from painting to rattan and stone. On this occasion Nindityo was forced to improvise as one of the mirrors was broken on arrival in Havana and he had to fill the frames with local bread and croissants that had a similar shape to the konde. A young artist less experienced with difficulties encountered in international exhibition, could be unnerved by such an experience.

Exclusions

Given the reliance of selectors on the Supangkat-Cemeti circuit, the Indonesian work preferred or excluded for biennales is, not surprisingly, similar to those mentioned in the chapter on the Cemeti gallery. Indonesian Modernists painters were not seen in biennales after the early 1990s and socio/political installations dominated selection.

The work of Indonesian women artists also seemed to be excluded from biennales, but this was more an indication of their remarkably low representation in Indonesian contemporary art generally. Dolorosa Sinaga, better known as Dolo, has carved out a career in sculpture against these odds, eventually becoming Dean of the faculty of Fine Arts at IKJ. She is seen here beside one of her works at her first major retrospective exhibition in 2001 which was held relatively late in her career. Most of her work represents women and is an appeal for their interests, such as family and children, their contribution to society and to be free from violence.[84]Interview, Dolorosa Sinaga in her home and studio, Jakarta, 18/05/02. Dolo’s work was not selected for biennales, most likely because it is categorised as within the Modernist tradition of figurative bronze sculpture and was not perceived as experimental.

By the 1990s gender parity was an issue of political correctness for international selectors and, where Indonesia was concerned, it proved difficult to meet. Three female artists apart from Arahmaiani have been selected for international exhibition, but of these, some question whether Mella is an Indonesian artist, Bunga Jeruk has only recently been selected for Asian shows and Marintan Sirait, although selected for three exhibitions, subsequently has been concentrating on other activities.[85]For Bunga Jeruk, see http://www.bungajeruk.net/bunga9899.htm accessed 07/03/07. Another artist, Fiona Tan, although born in Indonesia, lives and works in the Netherlands and does not … Continue reading Arahmaiani was by far the most often selected for international exhibition. It is not Arahmaiani’s work that is in question but her repeated selection as it implied the absence of any alternative. It was easier for curators to select a known artist who addressed familiar issues rather than research and understand the cultural conditions that restrict women in Indonesia and limited their participation in visual arts.

Arahmaiani rejected social conventions that limited female artists and their movements and frequently travelled internationally to participate in exhibitions and take up residencies. If artists are to gain the attention of curators and develop international careers, they need documentation, a history of exhibition and to be able to travel and accept offers of residencies. Many Indonesian artists have found this difficult and women artists from a Muslim and Javanese culture in particular. Although in modern urban Indonesia the role for women is expanding, women have been inculcated to prioritise family over career, and this has limited their opportunities in the arts.[86]Note: Samina Yasmeen, “Muslim Women and Human Rights in the Middle East and South Asia”, in Hooker, V. and Amin, S., eds., Islamic Perspectives on the New Millennium. Singapore, Institute of … Continue reading