Global artists

The transition to a global perspective in Indonesian visual art is particularly seen in the careers of three artists: Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani and Heri Dono.

Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani and Heri Dono addressed socio political issues in their art and, each in their own way, reacted to the repressive nature of the Suharto regime. Dadang, like FX Harsono, felt discrimination as the result of his Chinese ethnicity and made victimization the central subject of his art. Arahmaiani addressed the repression of women in a patriarchal Indonesian society and, by extension, social justice in general, and Heri reflected some of the absurd aspects of a society under Suharto’s dictatorship. There were little if any sales of their work in the early half of the 1990s and even exhibiting outside Indonesia could be made difficult by the regime. Heri, for example, was threatened by the Indonesian Embassy in London with problems about returning home if the catalogue of his exhibition was not withdrawn because it implied criticism of the Suharto government.

Even so, their socio/political art was attracting interest and coincided with a general rise of international awareness of Asian art. Selectors for major survey exhibitions sought art that reflected conditions within the artist’s country and as a result, Dadang, Arahmaiani and Heri were among a small number of Indonesian artists invited to exhibit overseas. Through residencies, invitations to exhibit and contacts, they developed international careers, all three spending a large part of their time globe-trotting. Heri was the first internationally recognized Indonesian artist of his generation and became a global art star. An examination of their careers illustrates these developments, beginning with Dadang.

Dadang Christanto

Dadang Christanto has had a remarkable career almost entirely constructed outside Indonesia. Dadang, Heri Dono and Eddie Hara were seen as ‘expatriates’ by their countrymen, as is stated in the catalogue published in 2002 for Dadang’s first exhibition in Indonesia since 1995:

The works of these three visual artists are more recognised within the global art circle than in their own country. This is because they exhibit their works more frequently in foreign countries, or also because they happen to reside abroad more often.[1]Introduction by the administration of Bentara Budaya in Wiyanto, H. 2002, The Meaning of Memory, catalogue for the exhibition of Dadang Christanto, Kengerian tak Terucapkan, The Unspeakable Horror, … Continue reading

In the 1990s living and working outside Indonesia allowed Dadang to address a history of violence, particularly against Chinese Indonesians, that had been suppressed by the Suharto regime. As with Harsono, this history directly affected his family. Dadang said:

“I was eight years old and living in a village. I did not understand about anything, and I know in 1965 early one morning my father was taken away in an army truck. The five of us (children) were still sleeping. My oldest brother was twelve, my youngest sibling was three years old. Since then I have never seen my father again.”[2]Hendro Wiyanto, “The Meaning of Memory”, ibid.

Dadang’s father, Tan Ek Tiiu, a Chinese shopkeeper, was a victim of the massacres that broke out in October 1965. His father was the focus of a racial prejudice that had its roots in the envy of the entrepreneurial success of the Chinese and this, combined with the accusation that the Chinese were associated with the PKI, the Communist Party, and responsible for the murder of the generals in the coup of 1965, made the Chinese a particular target. As Harsono had witnessed, a witch-hunt targeting Chinese erupted across the archipelago and denunciations escalated into mass killings in which military troops and Muslim zealots participated.

Like the majority of Indonesians affected by the violence of 1965, Dadang felt he could not speak about it: “I did not want to talk about these things during the Orba period (Orde Baru) as this would be the same as suicide.” As a Chinese and a victim he has felt himself to be a pariah, ‘lower than the lowest in a Hindu caste system’ he said; but he felt his art could be a means of resistance to the ‘facist regime’. He said in an interview with Hendro Wiyanto, the curator of his exhibition in Jakarta in 2002,

“Isn’t keeping quiet just the same as acceding to something? I hope that the event behind these works can become the basis in commencing a dialogue for healing myself and the general community.”[3]Bahasa Indonesia is an evolving language and combining words to create acronyms, such as ‘Orba’, is very common. Quotations are from personal interviews with Dadang in 09/04/2000, also Wiyanto, … Continue reading

Dadang’s art transcends this personal family experience to address what he considers the most significant feature of the 20th century: systematic violence. The Balinese writer, I Ngurah Suryawan, in an essay for Dadang’s exhibition in Jakarta in 2005 titled in part, Not to Get Killed Twice, wrote that the struggle between remembering and forgetting violent events had become a political issue because the Suharto regime suppressed debate and projected its own interpretation of events.[4]I Ngurah Suryawan, “The politics (Arts) of Representing Bitterness: Not to Get Killed Twice”, in Clark, C., Turner, C., Cribb, R., I Ngurah Suryawan, On the edge of the petal there are still … Continue reading Joseph Stalin was credited with saying, ‘A single death is a tragedy, half a million liquidated is a statistic’, which dehumanizes the victims and de sensitises the response of bystanders and witnesses. For Dadang, an effective work of art is one that summons empathy for the victim of violence by re creating a sense of their experience. Identifying personal experience within disastrous events restores power to the victims.

Despite his name, Christanto, Dadang says he is not religious; he converted to Islam when he married but does not practice. His mother practised Javanese animism which was not recognised as a religion and, atheism being equated with Communism, she nominated to become a Christian for the KTP, the identity card.[5]Dadang, interview, Sydney, 21/09/03. She was a batik cloth merchant and encouraged Dadang to study art after he concluded his basic education. He began by studying painting at the Pawiyatan Sanggarbambu, a sanggar or studio in Yogyakarta, and continued at a SMSR, Sekolah Menengah Seni Rupa or Secondary Art School from 1975 to 1979. During this time Dadang worked with, and was strongly influenced by, the activist poet and playwright, W.S. Rendra at the Bengkel Theatre. “It was a good time for me, raising my awareness of the political and social and to be part of the political opposition”, he said. Dadang continued his involvement there until the activities were banned in 1980 and Rendra was jailed. Dadang also credits Rendra with being the theatrical inspiration for the performances which have been a significant accompaniment to his artworks and a means to engage with the audience.[6]Dadang, interview, Sydney, 21/09/03.

In these performances he identifies with the victims, as in a performance given in Canberra in 2003 where the audience was invited to throw small bags of flour at Dadang and his son, Gunung. It was extremely uncomfortable to participate as directed so most members of the audience aimed above the two seated figures; yet the flour still burst and coated the figures in a shroud-like white powder.

In 2009 Dadang repeated this performance, developing the concept associated with it. He sat at the base of a wall hung with old, rusty agricultural implements that pointed downwards in a threatening fashion and when the audience threw the bags of flour, the backwash of dust filled the air and coated both the ‘victim’ and the ‘victimizers’, as if persecution has consequences for all involved. The title for this performance was Litsus, an acronym from Penelitian Khusus, a special investigation that used to be required for parliamentary candidates and has become associated with demanding a loyalty beyond the human rights and wishes of the people.

Dadang studied painting at ISI along with Nindityo Adipurnomo and Heri Dono and graduated in 1986. He then joined Puskat, or Pusat Kateketik, a Catholic organization run by Father Rudi Hoffmann. Father Rudi, known as ‘Romo Rudi’, was a radical political thinker influenced by Liberation Theory, Paolo Friere and the Brazilian director and political activist, Agusto Boal. From 1986 to 1990 Dadang worked at the Puskat in their communications studio and became a tutor for the Teater Rakyat, the people’s theater.

Dadang joined with the members of GSRB in their last group exhibition, Pasaraya Dunia Fantasi, or Fantasy World Supermarket, held at TIM in 1987, and he made contact with the alternative Jakarta art world that included Jim Supangkat, FX Harsono, Sanento Yuliman and activist intellectuals such as Arief Budiman and Ariel Heryanto. Not long afterwards, in 1992, Supangkat selected Dadang along with Heri Dono and Teguh Osternik for the Japan Foundation’s Southeast Asian exhibition in Fukuoka. Thereafter Dadang’s international career developed independently of any one gallery in Indonesia.

As proved to be the pattern for global artists, exposure in one exhibition led to selection for another and opportunities for residencies and the sale of work to major galleries. Dadang’s career is another illustration of the threads and repetitions of international selection. When, for example, Jim Supangkat selected him for the Havana Bienal in Cuba in 1994, he met Apinan Poshyananda who then selected him for exhibition in the New York Asia Society’s Tradition and Tensions exhibition in 1996.

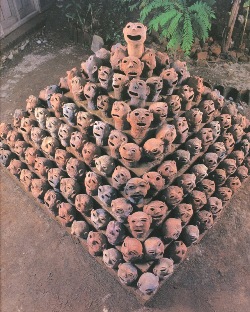

He exhibited a pyramid of terracotta heads titled, Kekerasan 1, or Violence 1 in the Traditions / Tensions exhibition that specifically referred to the victims of repression before and during Suharto’s regime. The heads were all similar but not exactly the same, with open mouths that could be smiling or grimacing but are, ultimately, vacant, for they are empty and are without bodies. The work is similar to that generally favored for selection in international exhibitions: the subject matter is dramatic and violent and, referencing recent Indonesian history, was exotic for a Western audience. The pyramid shape is reminiscent of the huge 9th Century A.D. Buddhist temple, Borobudur, not far from Dadang’s Indonesian home at Kaliurang in Central Java. It is covered with carved stone figures, many of them headless. Being an installation rather than a more conventional painting or sculpture, Dadang’s work was in accord with international contemporary avant-garde practice. Finally, like all effective works of art, it moved beyond being simply an illustration of the events of 1965. It recreates an intellectually and emotionally disturbing experience for the viewer, for the terracotta heads retain the shadow of ash from their firing that suggests the bodies have been burned.

Connections within connections led to a career based in Australia. While with activist students at UGM, Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta in 1991, he was introduced to Keith Foulcher, then a lecturer at Flinders University in South Australia, and he also renewed his connection with Jennifer Dudley, an artist and teacher from the South Australian School of Art. He was offered a four-month residency in South Australia during which he gave a talk at an Indonesian seminar at the Canberra Contemporary Art Space. There he met David Williams, Director of the Australian National University School of Art, and Professor John Clark. Williams then referred Dadang’s work to Caroline Turner who came to his studio in 1992 and selected him for the first Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1993 and again in 1999. He considers APT /1 most important in gaining him international exposure.

Dadang exhibited and gave performances at both APT/1 and APT/3 where his performance, Api di Bulan Mei, 1998, Fire in May, 1998, recreated the horror of the riots in the previous year. He performed a dance of mourning beside a large scale burning figure crowned with a white ceramic head, one of a field of figures that, after dark, were all burned.

Dadang developed a particular association with the APT administrative team during the 1990s which directly led to major opportunities and culminated in the sale of his installations to a number of Australian public art galleries.[7]Dadang Christanto’s CVs are to be found at http://www.raftartspace.com.au/dadang.html and http://www.shermangalleries.com.au/artists/inartists/artist_profile.asp?artist=christantod accessed … Continue reading

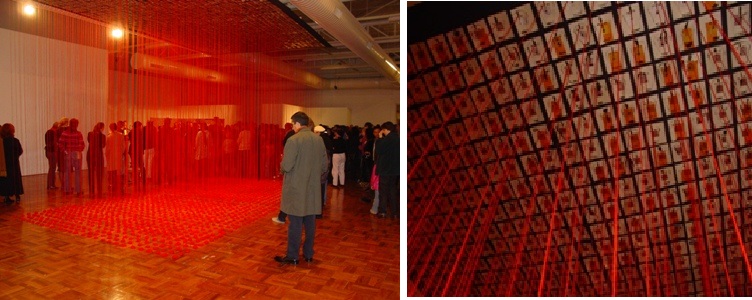

His work, Hujan Merah, Red Rain, was exhibited in the Art and Human Rights project organized by Caroline Turner and Christine Clark through the Humanities Research Centre at ANU in 2003. Drawings of heads covered the ceiling from which strings of red wool fell to the floor and curled in pools. The heads had the blank face of universal victims and the strings of wool create a curtain of blood. Hujan Merah was purchased for the Australian National Gallery and subsequently the ANG also purchased Dadang’s Heads from the North, an installation of bronze heads which protrude from the pool in the gallery’s sculpture garden.

As with his performance pieces, his installations have travelled the world, re worked in each site. One major work, They Give Evidence, has had a remarkable journey from its inception in Indonesia. It was exhibited in Japan and Brazil before returning to Indonesia and it finally ended at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia.

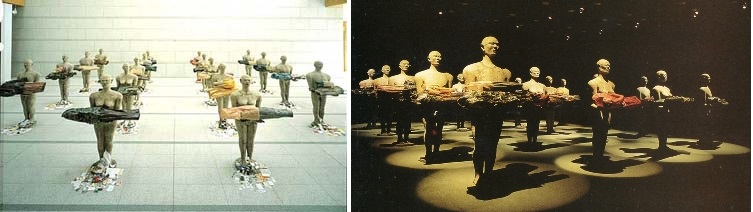

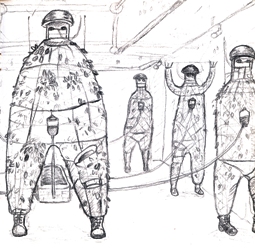

The work was funded by a grant from the Japanese government. It originally consisted of twenty figures, male and female and larger than life, constructed from a ground brick mixture used by the people in his home village of Kaliurang for their buildings and who also assisted him to make them. All face in one direction and hold in their outstretched arms fiberglass stiffened clothing in the shape of the bodies that once wore them. The figures are the victims of 1965 and the clothing represents the recent victims of the riots with the collapse of the Suharto regime: the victims are presenting the victims.

They Give Evidence was first shown in Art in Southeast Asia, 1997, in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and then in Hiroshima, Japan. Members of the audience left offerings and mementos at the feet of the statures that Dadang understood were made in the spirit of apology for the Japanese occupation of Indonesia during the Second World War, although his works have provoked a similar response with offerings in other circumstances. Then, after the exhibitions in Japan, six figures from the work were shown in the XXIV Bienal de Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 1998.

In comparison to the international empathetic response to the work, the reaction in Indonesia was very different. Dadang exhibited They Give Evidence as part of his retrospective at Bentara Budaya, the Kompas exhibition space, in Jakarta, in July 2002. Local residents objected to the figures which were installed in the grounds outside the arts complex, saying that that the figures, being naked, were pornographic and local children were playing obscenely with them. Dadang and the curator, Hendro Wiyanto, discussed the situation with a delegation from the residents and Dadang agreed to cover the figures with black plastic. When he had used plastic like this previously, he felt it had an interesting effect as the figures looked ‘like Ninja’, he said.[8]Dadang speaking at a public lecture, University of NSW, College of Fine Arts, October 8th, 2003. Dadang had previously wrapped figures in black plastic in his installation for APT/3. But the day after the exhibition opened, at Friday evening prayers in the local mosque, the Imam said he would report the exhibition to the Council of Ulamas, the powerful religious leaders, and the Kompas administration was sufficiently concerned that they had the figures removed and stored.

Many articles were written about this experience, including one by FX Harsono who pointed out that the naked human form was commonly used in artistic expression; and he argued strongly against acceding to pressure from minority groups.[9]Harsono, FX, 2002, Pameran Seni Rupa Dadang Christanto, Menyodorkan Bukti Kekerasan Masih Terjadi, Art Exhibition of Dadang Christanto, Proving that Violence Still Occurs, Kompas, Jakarta. … Continue reading But debate was raging over the legislation for new pornography laws and, in this heated environment, Dadang’s figures lost their status as an autonomous art object and became a tool for the exercise of moral and religious influence. This was not going to be the only example of rising Islamic fundamentalism affecting the arts after Reformasi.

The work finally ended its journey in Australia. In 2003 the Art Gallery of New South Wales purchased They Give Evidence, placing it as the centrepiece at the opening of their new Asian galleries. Dadang was invited to take up a residency at the University of NSW, College of Fine Arts, to restore the work and install it.[10]The history of the work, They Give Evidence, was confirmed in a phone conversation with Dadang, 9/10/03

Since 1999 Dadang has been a permanent resident in Australia and has taught at the School of Art and Design, University of the Northern Territory, Darwin. Living and working outside Indonesia has given him access to information which has influenced his thinking and allowed him to express his ideas freely. He produced commercially saleable works on paper and is represented by Sherman Galleries in Sydney, and his installations have been bought by major museums. In 2005 he and his family moved to Brisbane, Queensland, and he resigned from teaching, the sale of his works allowing him to practice full time as an artist.

As many socio/political artists found, the downfall of the Suharto regime initially seemed to remove the main cause of their objections, but many issues remained and new problems arose. The victims of disaster now became a subject for Dadang’s art.

In May 2006 the Indonesian resources and exploration company, Lapindo Brantas, while drilling boreholes for gas in the Sidoarjo region of East Java, struck an underground reservoir, causing an eruption of hot sulphurous mud. The event is now known as the Lapindo disaster and the mud has continued to flow since then, burying villages and land, poisoning rivers and destroying communities without any foreseeable likelihood that the flow will stop or be stemmed by any man-made control. Victims were relocated but reparation was uncertain and was finally buried under suspicion of corruption and arguments over responsibility. The media ceased to report the situation as it is no longer considered ‘newsworthy’. The people of the area have been abandoned, their societies dislocated by the loss of public and private structures, their livelihoods destroyed, their communal histories lost, and their health endangered by toxic mud and fumes.

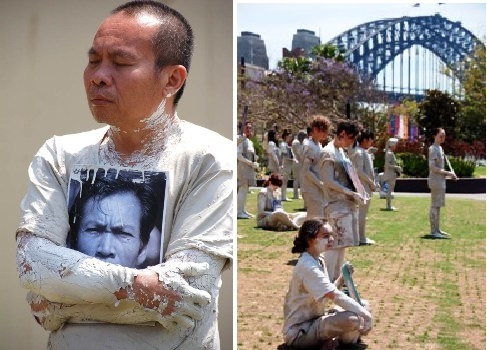

Dadang and the Urban Poor Consortium, a Jakarta-based group of NGOs providing welfare and advocacy for the disadvantaged, gathered four hundred people from Sidoarjo and two hundred people from Jakarta to bear witness to the human consequences of the catastrophe. On Human Rights Day, 10 December, 2008, they held a twelve hour vigil at Tugu Proklamasi (the Proclamation Monument) in Jakarta, a site commemorating freedom from Dutch colonial control and which was loaded with symbolism. Covered in brown mud, the participants stood, sat and kneeled, silently holding the photographs of the displaced people of Sidoarjo whose lives had been destroyed by the mud flow. One observer commented that the scene was particularly powerful after dark when candles were held by the participants.

The performance in Jakarta was followed by similar performances in Sydney Australia. Dadang and a small group of volunteers streaked in white clay, stood or knelt in a three hour vigil in the Gallery 4A space in 2009 and repeated the performance outside the Museum of Contemporary art at Circular Quay in 2010. The brown clay of Sidoarjo was not available but the white clay added a touch of ghostliness and suggested mourning and death.[11]Survivor is to tour regional galleries in Australia in 2012/2013. A three hour vigil will be maintained by mud-caked volunteers followed by an exhibition of the remains and documentation

The events highlight the variable quality of performance art. The public events at both Tugu Proklamasi and Circular Quay caught the attention of the passing public and became an opportunity for activist art to raise awareness, while the performance at Gallery 4A was an art event, the consciousness-raising aspect dissipated by the wine and conversation of an exhibition opening. Dadang Christanto is now a mature-aged artist with a body of work that raised awareness of conditions in Indonesia and connected with audiences at a sensitive and personal level. The debate will continue as to whether addressing Indonesian social and political issues from an expatriate position will achieve his activist aims.

Arahmaiani

Arahmaiani was the one female Indonesian artist to develop a career through international exhibition in the 1990s, but her repeated selection obscured the fact that there were so few other women artists. The conventions of Indonesian culture and society have made developing a career in the visual arts particularly difficult for women. Arahmaiani has been selected for at least eight international survey shows between 1996 and 2002, which is a remarkable number in comparison to all Indonesian artists, both male and female, and she is the one female artist to develop an international career on the same scale as that of Heri Dono and Dadang Christanto. The reason she has been chosen is because her performance works raised issues concerning the patriarchal, Muslim/Javanese society that few artists, either male or female have addressed. Her work is also an indication a difference between local and global preferences, for not only is the medium of contemporary performance not well understood in Indonesia, but there is a general aversion to overt feminist content in art.[12]Note the opinions reported in Prasetyohadi, “Controversy surrounds the merits of performance art”, The Jakarta Post, 16 April, 2000, an article concerning the Jakarta Performance Art Festival at … Continue reading

She has been an activist for gender in Indonesian art yet as a role model, she is too difficult for many other women artists to emulate as she rejected the conventional roles assigned to women. Her statements can be forceful: she said,

“… equality can only be implemented after several prerequisites are met: the destruction of male domination over females, political openness and of course political change.”[13]Arie Dyanto, “Kebudayaan itu Berkelamin komik tentang Arahmaiani”, Culture is Sexist, a comic about Arahmaiani, Aspek-Aspek Seni Visual Indonesia, Politik dan Gender, Yayasan Seni Cemeti, … Continue reading

In pursuit of these goals she has exhibited a packet of condoms beside the Qur’an, invited an audience to write on her body and has drunk whisky during a performance, all of which are extremely challenging activities in the context of a Muslim culture and for which she has been criticized and threatened. Yet she herself is Muslim and she has protested the stereotyping of Muslims and Indonesians after the terrorist acts of September 11th. Initially, like many in Indonesia, she resisted the term ‘feminist’, believing that there are distinct differences between Western feminism and the growing feminist movement in Indonesia. She has been defined as a feminist activist in international exhibitions, yet according to Arahmaiani, the Western aims of sexual liberation and individual self-fulfilment are inadequate in the face of inequalities in Indonesia that are the result, she says, of colonial histories and uneven modernities.[14]Interview, Arahmaiani, Jakarta, 25/6/01. Note, for example, her inclusion in the exhibition, Global Feminisms, Brooklyn Museum, 2007, see Reilly, M. and Nochlin, L., eds, 2007, Global Feminisms, new … Continue reading Perhaps her life and her work is an illustration of the inherent contradictions in Asian Feminism.

Arahmaiani, often known as Iani or Yani, holds, though, an almost mythological position in Indonesian and Asian contemporary art, not only for her contentious performances, but because of her personal history. Her family in Bandung has remarkably diverse antecedents that include Chinese and the early Batavian Dutch Jews as well as Javanese. The family has a broad educational background. Her father, a Muslim scholar or Ulama, has studied overseas in USA and the UK and has been prominent in the MPR, or the People’s Consultative Assembly, and her grandmother ran a pesantren or school for Muslim girls. Speaking at the seminar held in conjunction with the Edge of Elsewhere exhibition in Campbelltown, N.S.W. in 2010, Arahmaiani described herself as totally hybrid due both to her family background and her nomadic career.[15]Edge of Elsewhere was a three-year project for the Sydney Festival shown at Campbelltown Arts Centre and 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, between 2010 and 2012

Arahmaiani has an enquiring mind and was non conformist from an early age. When as a child she declared she wanted to be a nabi or prophet when she grew up, she was offended to learn that it was a role reserved for men. She became further aware of social inequalities by observing the disparity between her family and their servants, and social justice has, from the beginning, been the focus of her art work. Her education has been diverse and on-going: among many influences she cites Rendra for assisting her learning about Javanese culture and Suprapto Suryodarmo, the Javanese movement artist, both of whom contributing to her concept of performance. Early Buddhism in Java also has continued to interest her and has led to her most recent involvement with Tibetan Buddhists.

She entered ITB in 1979 and participated in activist art events while a student, but after the birth of her daughter outside marriage, she encountered social censure. A street event that was seen as a challenge to the regime resulted in her being interrogated and held in home detention for a month. She was only released on condition that she took no part in public activities. Feeling threatened by the military, she left Indonesia and, financed by her grandmother, she studied in Australia. In Sydney she attended the Paddington Art School for a year and ‘hung out’ with hippies and punks. It was her first experience of Western culture and she found it overwhelming. She said, “I had come from a very repressive culture and here, they had much more freedom to express themselves”.[16]Interview, Arahmaiani, Sydney 8/1/12. Most of the details of Arahmaiani’s personal history have been derived from interviews and conversations between 2000 and 2012 When she returned, ITB refused to re enroll her because of her political activities and she began a life living on the streets. She found at first that it was fun, she said, “Wow! All this going on! It was exciting!”….and then it was difficult, “…you learn to protect yourself,” which she did by belonging to a gang.[17]Interview, Arahmaiani, Bandung, 25/05/02 Such experiences have contributed considerably to the legend that surrounds her.

In 1991 she obtained a grant to study in the Netherlands and while attending the Academie voor Beeldende Kunst, in Enschede, she was introduced to the work of Joseph Beuys. She found that although the work was made in a German cultural context, Beuys offered a way for art to resolve social issues in Indonesia. After only a year she had to return to Indonesia and again, she lived on the streets.

As with a number of other Indonesian activist artists, she had moved away from two-dimensional works to installation and performance art as a challenge to the status quo both socio/politically and artistically. While Dadang Christanto accompanies his installations with a performance, Arahmaiani, although trained as a painter, has made performance itself central to her work. She does, though, work in other media, as she said, “There is no support for the kind of work I do [in Indonesia]. Forget it, no way! I am trying to influence the social process within my own community, trying to push for change. However I have to survive, to be practical, so this is why I do some paintings or sell my costumes from my performances.” [18]Gina Fairley, “It’s OK to Undress Me: Indonesian artist Arahmaiani on landscape painting, market terrorism and the absence of art in Malaysia”, Kakiseni.com … Continue reading

Her first solo exhibition was held in 1994 in an alternative art space, Oncor Studio, in Jakarta. The confrontational title of the exhibition, Sex, Religion and Coca Cola, associated sensitive topics with global commodities and, like Beuys, she used everyday objects in a way that suggested concepts beyond their conventional use. Two works in the exhibition were sufficiently controversial that they have not been exhibited in Indonesia again. One, a painting, titled Lingga – Yoni, depicted Hindu symbols of male and female genitalia painted on a background of Arabic, Malay and Hindi scripts, with the female yoni above rather than under the lingga as if challenging male dominance. The Hindu reference combined with Arabic was also a challenge to Muslim orthodoxy and recalled the cultural hybridity of Indonesia where Islam has been modified by other cultures and religions. It was, though, another work, Etalase, or Display Cabinet, that attracted the most objections. Arahmaiani had arranged a series of objects in a vitrine as if they were a museum exhibit for contemplation, but by placing religious symbols beside commercial objects, the implication was that all had become commodified and devalued. The placement of the Qur’an beside a packet of condoms provoked particular outrage and members of a Muslim fundamentalist group removed the items and physically threatened her, promising to publicize the incident in the Muslim press.

A number of the issues that appeared in this first solo exhibition are seen in her later work. Arahmaiani confronts repressive sexual and religious taboos, particularly those aimed at women, and she challenges global capitalization, symbolized by her repeated use of the Coca Cola bottle. The Coca Cola bottle for her is both a commodity and a phallic symbol that represents lingga and life but also the name, coca, is associated with cocaine and addiction.[19]Interview, Arahmaiani, Sydney 8/1/12

Apart from Arahmaiani, few Indonesian artists have made religious references in their work and references to gender tend to be made in an oblique fashion, not in her confrontational way. Feminism has been treated with suspicion in Indonesia despite the principle of gender equity being embodied in article 27 of the 1945 Constitution. Professor Saparinah Sadli, who was, amongst other roles, chair of the Indonesian National Commission on Violence wrote,

“The terms ‘feminism’, ‘feminist’ and even ‘gender’ are still questioned by the majority of Indonesians. They are considered by many to be non-indigenous concepts that are irrelevant to Indonesian values.”

It was, she said, considered to be a Western concept that was anti-men and promoted the acceptance of lesbianism.[20]Saparinah Sadli, “Feminism in Indonesia in an International Context”, in Women in Indonesia, Gender, Equity and Development, Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, Eds., Institute of Southeast … Continue reading There has, though, been a growing interest in feminism amongst the younger generation of Indonesian female art students in first decade of the twenty first century. It has coincided with the rise of Islamic fundamentalism, the nemesis of feminism, and art expressing ideas relating to gender have been targeted by fundamentalist groups.

Arahmaiani has been active in the support of women, has networked amongst artists and organizations both locally and internationally and has organized a regular meeting for young women artists in Yogyakarta. She has written essays and published regularly, including an article written for Visual Arts titled Perempuan Perupa dan Revolusi Kebudayaan, Women Artists and Cultural Revolution, where she expresses her ideas and the problems facing women artists since the Suharto regime. She wrote:

“Indeed, women are faced with the same obstacles as men, they must compete in world arena as well as in the art market. However, remember that women’s position is not considered equal with men within Indonesian culture and its patriarchal system remains dominated by masculine voices – so women artists have to work much harder if they want to obtain the same positions and opportunities as men.”[21]Essay written 11 March 2011 in Yogyakarta for Visual Arts and provided by Arahmaiani

The patriarchal nature of Indonesian society marginalized or ostracized non conformist females and made a career in the arts very difficult for women. Public discourse surrounding the role of women was, and in many respects, still is, greatly influenced by the state policies of the New Order regime, where hierarchical Javanese customs combined with Islam to make the patriarchal family the institutionalized basis of the state. This was referred to as State Ibuism by Julia Suryakusuma, writing in the mid 1990s.[22]Julia I. Suryakusuma, “The State and Sexuality in New Order Indonesia”, in Laurie J. Sears, ed., 1996, Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, Duke University Press, p.98

Suharto himself defined the role of women as bringing:

“… Indonesian women to their correct position and role, that is as the mother in the household [ibu rumah tangga]… We must not forget their essential nature [kodrat] as beings who must provide for the continuation of life that is healthy, good and pleasurable”.[23]Soeharto: My Thoughts, Words and Deeds: Autobiography as told to G. Dwipayana and Kamadhan K.H.quoted in Sylvia Tiwon, “Models and Maniacs Articulating the Female in Indonesia”, in Laurie J. … Continue reading

If the Kodrat Wanita, supposedly a woman’s God-given nature to give birth, is accepted as the defining role of women, this determines moral value and appropriate behavior and leaves very few avenues for independence. The concept exists of a Kodrat for men, but is rarely applied. The only recognized state for women was within marriage and this was reinforced by the interpretations of Kyai, or Islamic religious leaders, and Ulama, or scholars. Women’s Islamic organizations, and Arahmaiani herself, have continually urged the Kyais to re interpret the Qur’an in favor of women’s equality with men in order to improve conditions for women. But Arahmaiani said they would not debate her in public, there being many topics they would not discuss with her as she is a woman.[24]Lies Marcoes, “Women’s grassroots movements in Indonesia: a case study of the PKK and Islamic women’s organisations,” in Katheryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, eds., 2002, ibid, p.194 and … Continue reading

In 2011, post Reformasi, Julia Suryakusuma questioned whether ‘State Ibuism’ was still operating: What has changed is the role of the state. The shift in the constellation of forces as a result of Reformasi and democratisation that meant the state no longer monopolises public life also means the social construction of womanhood is no longer completely state – dominated. Now it is open to a range of interpretations. As a result, the dominant social construction has become a predominantly Islamic one – or at any rate, the version of Islam that conservatives would like us to believe requires subordinate, compliant women.[25]Julia Suryakusuma, 2012, “Is state ibuism still relevant?”, Inside Indonesia 109, Jul-Sep. http://www.insideindonesia.org/feature/is-state-ibuism-still-relevant-01072924

The more extreme the Islamic sect, the more likely it was to restrict the freedom of women and seek a justifying text from the Qur’an. The increased wearing of the headscarf or jilbab, the potentially restrictive consequences of the anti pornography law of 2008 and the application of Sharia law in the provinces has caused concern among moderate Muslims in Indonesia, who equate the rise of fundamentalism with foreign influence from the Middle East and not based in local traditions. Civil as well as religious laws place women at a disadvantage in comparison to men. Polygamy, for example, although discouraged by Suharto, was legal, and as recently as 2008 attempts to ban it have failed. The male-dominated legal system provides no effective civil laws to protect women and their children in a polygamous relationship if they are superseded by another wife, or abandoned.

Media, magazines, television, especially the soap operas called Sinetron, and film reinforced the role for women. Sita Aripurnami discussed the way in which independent women were negatively portrayed in her delightfully named paper, Whiny, Finicky, Bitchy, Stupid and ‘Revealing’ – The Image of Women in Indonesian Films. She wrote,

“One role often seen on the screen is that of a woman with a family, working outside the home. Her working is almost always equated with selfishness and seen as a threat to her family. Her husband will turn to another woman, while her children will be neglected and become delinquents or fail in school.”[26]Sita Aripurnami, “Whiny, Finicky, Bitchy, Stupid and ‘Revealing’ – The Image of Women in Indonesian Films”, in Mayling Oey-Gardiner and Carla Bianpoen eds., 2000, Indonesian Women The … Continue reading

Ideal Javanese behavior, to be restrained and maintain harmony, compounds Muslim strictures. Women are expected to be demure, polite, sexually pure and discreetly dressed. As artist, Astari Rasjid, said, “I was taught a girl must be pleasing, smile and have good manners, and look appealing even if she feels miserable.”[27]Carla Bianpoen, “Highlighting the Goddess Within Women”, The Indonesia Tatler, February 2001 Yatun Sastramidjaja wrote in her article, Sex in the City, subtitled, Between girl power and the mother image, young urban women struggle for identity:

Ideally middle-class girls are supposed to merge the two roles of girl power and Kodrat Wanita without much difficulty. Yet in reality they are often confronted by stark contradictions. The duality of social discourse on female gender produces moral confusion, in which the distinction between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ behaviour is no longer clearly defined.[28]Yatun Sastramidjaja, “Sex in the city, Between girl power and the mother image, young urban women struggle for identity,” Inside Indonesia, April – June 2001, no 66, p.14

Some female artists have had notorious difficulty continuing their careers after marriage, among them Lucia Hartini and Kartika Affandi;[29]Detailed in Astri Wright, 1994, Soul, spirit, and mountain: preoccupations of contemporary Indonesian painters, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, pp 132 – 142, also in the individual … Continue reading but the younger generation believes they will be able to negotiate their own space and preferences. A female graduate of ITB in discussing marriage said,

“Ya… but there is a compromise, there is always a compromise. My husband won’t be that blind. I guarantee I won’t choose (a man like that)”.

This graduate had been invited to exhibit and offered career opportunities, but a year later she had married, and like many, disappeared from the art world.

The female artists who did address issues of gender in their own work were often those who had transgressed social conventions they found stultifying and, bruised by the experience, used it as a subject for their art. Often the female body was used as a platform for feminist issues and the expression of difference from men, although this attracted criticism and tended to marginalize the art in the ghetto of ‘women’s issues’.[30]Carla Bianpoen, Farah Wardani, Wulan Dirgantoro, “Women in Indonesian Modern Art: Chronologies and Testimonies” in Bianpoen, Carla, Wardani, Farah and Dirgantoro, Wulan, 2007, ibid, p.31

Arahmaiani’s use of her own body in performance art was, she said,

“… a means of expressing myself – expressing my memory, joy, happiness, sadness, frustration and dream through my body…” and a way “…to break out from the locked Indonesian art circles…” [31]Catalogue, Asian Performance Artists, The 5th Asian Performance Art Series, Shinshu Summer Seminar, 2000, p.19 and p.11. Carla Bianpoen, Farah Wardani, Wulan Dirgantoro, “Women in Indonesian Modern … Continue reading

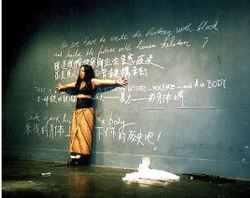

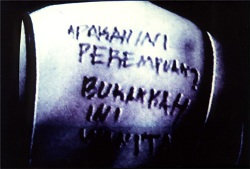

Arahmaiani has done a number of performance works involving writing words on her body, either writing on herself or inviting members of the audience to do so. She presented His Story in Performance Art Festivals in Jakarta, Taiwan, Germany and Japan between 2000 and 2001. At various times she held a gun beside her head, written the word, ‘domination’, on her arm and posed in front of a wall with the phrase in different languages: ‘do we have to write history with blood and build the future with skeletons?’ Later versions have been less confrontational, Arahmaiani inviting the audience to write words of personal significance to them on her skin as an exchange of meaning between artist and audience. Such performances are familiar in Western experimental art and have been seen in the work of Marina Abramovic and Yoko Ono; but Arahmaiani’s performance in the context of an Indonesian and Muslim culture was extremely contentious, body contact between men and women only being sanctioned within marriage. In the case of the performance at the French Cultural Centre in Bandung, 1999, Dayang Sumbi Rejects the Status Quo, (Dayang Sumbi being a mythological West Javanese beauty), she also removed part of her clothing and members of the audience tried to make her dress again.

Performance is an ephemeral art form and involves a specific circumstance and relationship to the audience, a performance in Indonesia potentially having a different impact and meaning than the same performance at an international venue. Because of its specificity, it is also difficult to assess: only the few present at the time can assess Aramaiani’s art on the basis of original experience. The recordings of her performance on video or DVD only document rather than recreate the art work. It is Arahmaiani who has become the work of art – the concept has transferred from the performance to the performer and she herself embodies the ideas of her art. Her dramatic story and lifestyle outside the normal conventions pertaining to Indonesian women, is well known and has become mythologized, both in the Indonesian art community and beyond, her socio/political activism and reputation travelling the international circuit through curatorial networks. Arahmaiani has become the representative of Indonesian gender issues at every major international exhibition from ARX, the Artists’ Regional Exchange in Western Australia in 1995, to the Venice Biennale in 2003, and more since then.

Arahmaiani physically has led a peripatetic life without a home base which contributes to her intellectual position, shifting between the local and the global. Like many global artists, she is attempting to negotiate a space for her Indonesian identity in an international context but, while her performances contribute to international understanding of Indonesian issues, she has been criticized for being estranged from the community she wishes to influence and not actually being effective in Indonesian society.

In conversation with Arahmaiani at Artspace, Sydney in 2007, Ray Lagenbach said:

“Many public intellectuals are ‘border intellectuals’ – they are inside their nations and they are also outside their nations. They work trans-nationally as you do, in that way of interfacing with a global economy supported by contextual institutions such as biennials, triennials…”[32]Ray Lagenbach, artist, writer and curator based in Kuala Lumpur and head of media, School of Performance and Media, Sunway University, Malaysia, in conversation with Arahmaiani, Artspace, Sydney, … Continue reading

Arahmaiani is working across areas that are perceived as contradictory, shifting between positions and trying to find a balance. She defends herself against the suggestion she has lost her Indonesian identity in the global context, saying:

“All of my work is related to my country, the hard situation for the people here which I want to comment on in ways that are sometimes quite negative…..But I feel strongly connected to this place where I was born, a feeling that is becoming even stronger as I travel and get some distance.”[33]Barbara Pollack, “Feminism’s New Look”, ARTnews, Sept. 2001, http://artnews.com/issues/article.asp?art_id=971 accessed 09/10/06

Although exploring local issues, Indonesian art should not remain isolated, she argues, and should be measured against international standards. In Indonesia she has been accused of being a ‘Western capitalist’ and supporting globalization yet she also criticizes global capitalism in her work.

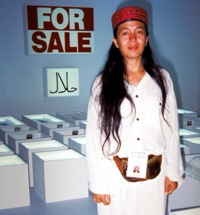

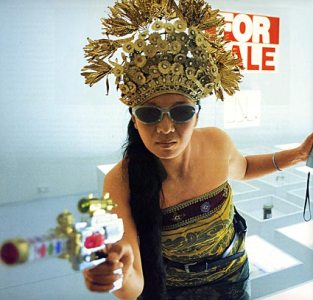

Her work in one of the first international survey exhibitions she attended, APT/2 in 1996, was a performance and installation titled, Nation for Sale, which commented on the commercialization of the national culture and the promotion of commodities as objects of desire by multinationals. The iconic image of her, dressed in the costume of a Balinese dancer with sunglasses and waving toy gun and a Star Wars wand, conflated traditional culture with popular entertainment. It subverted the exotic image of Indonesia promoted by tourism by demonstrating everything has been commercialized. She said,

This capitalistic system somehow forces my people to adopt the value system of the capitalist so they start selling everything that they have including their country. So the country sells everything. [34]Datuin, Flaudette May V, 2000, ibid

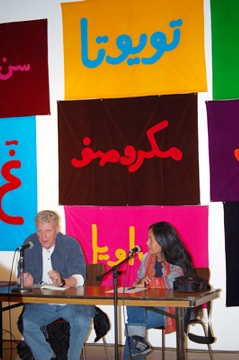

In the exhibition at Artspace over ten years later, Arahmaiani continued to explore global capitalism. The pieces mounted on the wall behind Arahmaiani at Artspace spell out ‘Microsoft’, ‘Toyota’, ‘Nike’, ‘Sony’ and ‘General Electric’ in Jawi, or Malay Arabic script. They are the names that symbolize multinational capitalism which, in Indonesia, is considered Western. Her intention was to present these icons to those who equate globalization with the West and by using locally-understood script, imply that it has local consequences as well.

She is critical of the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Indonesia, while at the same time being critical of Western attitudes to Islam, and she continues to identify herself as a Muslima. In a paper she presented in Solo, Central Java, she wrote:

“So what has actually happened to Indonesia’s Muslim community? Has it really lost its tolerant, flexible image – replaced by one that is hard-line, closed and filled with threats of violence? …..Why is it that religion has become the means of defining national life?”

And in the same paper she commented:

“On the other hand, the general state of the global system, which often marginalizes non – Western cultural groups and rarely pays heed to the spiritual life, is complex and motivates the need to emphasize our identity.”[35]A paper delivered by Arahmaiani in Solo, March 2011 titled Negeriku Diambang Kehancuran? Is my country on the verge of destruction? Email copy provided by Arahmaiani

She has reacted strongly to the West’s association of Islam with terrorism and, since the attacks on American territory on 9/11, has developed a body of work defending Islamic identity. In an exhibition titled, Stitching the Wound, shown at the Jim Thompson House, Bangkok, in 2006, Arahmaiani worked with the Ban Krua weaving community, a Muslim minority group that had been persecuted in Thailand. They suspended a series of soft, three-dimensional letters in Jawi script made from vibrantly colored padded silk, the letters forming the words, ‘I love you’. She sought to counteract the stereotypical image of violence associated with Islam in the West and the fear of the Muslim minority in Thailand with warm, playful, shapes and meanings. Although blogs on the Internet indicate that those who can read the Jawi script are delighted and amused, even without a translation, the message is relayed by the colors and shapes.

It remains to be seen if a community of like minded people in Indonesia will support Arahmaiani’s ideas and whether a distinctly local version of feminism will take root. Meanwhile, in 2010 Arahmaiani undertook a new direction, developing a friendship with Tibetan Buddhist monks in a monastery two hour’s travel from Yenshu, Qinghai, also known as the Kham region of Tibet. When Arahmaiani was part of an Indonesian exhibition in Shanghai, funding was made available for travel, and she nominated Yushu as there had been an earthquake in the area which reminded her of the trauma of the Yogyakarta earthquake in 2006. This brought her in contact with local monks and they began a dialogue concerning the the natural environment and the pollution affecting it which has led to developing local environmental programs. Once again, working with marginal communities rather than with the art world, Arahmaiani has raised awareness concerning potential threats to the area which is the source of the three major rivers, the Yangtze, the Mekong and the Yellow River. Where these activities will lead is too soon to tell but they are global issues for a global artist.[36]Details from conversations and a paper written Passau, 12 August 2011, provided by Arahmaiani

This work is discussed in detail in the article, Arahmaiani in Tibet

Heri Dono

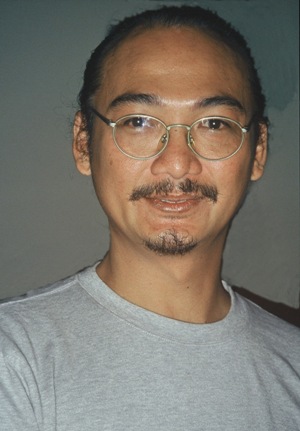

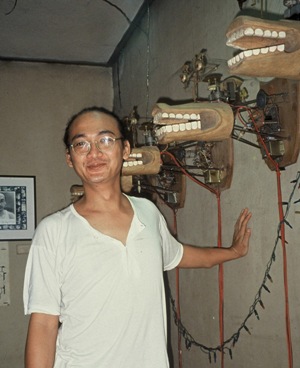

While Arahmaiani struggled with international perceptions of Islam and local perceptions of her activism, Heri Dono has been embraced as the personification of Indonesian contemporary art. Of the Indonesian artists selected for survey exhibitions overseas, Heri was the first to develop an international career, time and again being chosen as the representative of Indonesian contemporary art and often the sole representative.

From the beginning of his career and even before as a student, Heri Dono’s approach was experimental and contentious and he naturally associated with the network that was alternative to the establishment art of the commercial galleries, which included Mella, Nindityo, Cemeti, and eventually Jim Supangkat. His early and swift rise to prominence was based on an inventive and creative artistic vocabulary but also his ability to navigate international power structures and obtain residencies. He was the right artist in the right place and was regularly referred through the connections that are the power lines of the art world until he became Indonesia’s globe-trotting art star. An examination of Heri’s career will elucidate the qualities that led to his success and the art world mechanisms that contribute to it.

Heri Dono was born in Jakarta but Yogyakarta became his home base. His father, who had been in the army under Sukarno, was forced to distance himself from this association after the coup in 1965, and he opened a print works in Jakarta. Heri’s mother sent him with his brothers and sisters to a Catholic SMA (senior high school) not because they were either Christian or religious but because she believed there was more discipline in the teaching there. If anything, where religion is concerned, Heri is nominally an abangan Muslim or more relaxed in his Muslim practice,[37]See Geertz, C., 1960, The Religion of Java, Glencoe, Ill., Free Press, p. 5. Geertz discusses the difference between the more strict forms of Islam, known as santri, and the abangan tradition that … Continue reading and eventually he used a range of spiritual references in his work that he considers are animist. As was common, there was no art education in his school, but Heri took a course for making cinema posters. In the 1970s, living not far from Pasar Senin, he could catch a bus to the newly constructed arts centre, TIM, in Menteng in the heart of Jakarta, where he could ‘hang out’, see the exhibitions and listen to the debates.[38]Heri, in conversation, Sydney, 23/03/2006 In 1975, as a young student, he was impressed by the Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru protest, which influenced his choice of art academy and, rather than attending the smaller academy, IKJ, in Jakarta, he chose the prominent and historically significant Institut Seni Indonesi in Yogyakarta.

Since the 1980s Heri has lived in Yogyakarta and feels he is part of the community there, despite the amount of time he spends overseas. Having got lost in the little lanes that constitute what is effectively his kampung, or village community, I was eventually guided by a local who whooped: ‘Heri Dono, pelukis! Ya, saya tahu!’ (Heri Dono, the painter! Yes, I know him!) He lives on the other side of a lane beside the Bioskop Mataram, the local cinema identified by movie posters plastered on the walls, and the name appeals to Heri’s sense of humour: the juxtaposition of Bioskop, or cinema with the name of the great Mataram kingdom of Indonesia’s past history.

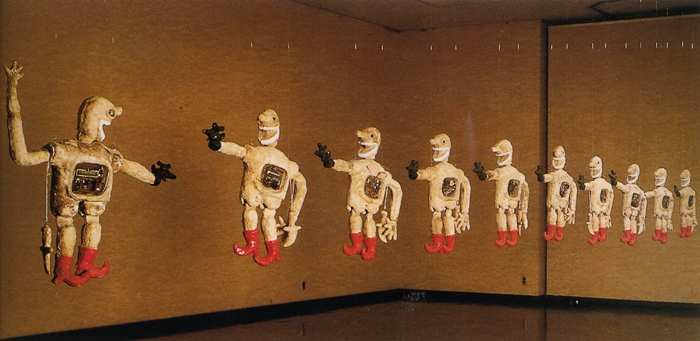

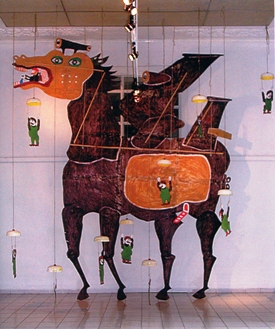

Heri’s house is a testimony to the ideas and materials he has collected and cannibalised. A figure in red boots with an electronic panel inserted in its torso is suspended from the ceiling, apparently left over from his installation, Badmen, 1991, now in the collection of the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. Mounted along one wall are the machine dragon heads of his work, Watching the Marginalised People, 1992, and on other walls there are Topeng masks, an old-fashioned telephone, presumably not functioning as there is a modern one below, posters, sketches and pinned objects. There are odd toys: a doll with a gun in its hand and another small plastic doll is attached to a fan so it rotates when the fan is switched on. It is a visual introduction to the often bizarre combinations of traditional arts with modern detritus that form the basis of Heri’s work.

At ISI in 1980, Heri became one of the small group of students to resist the conventional teaching which, in Heri’s case, were the constraints of the painting department.

He said:

“When I was a student I questioned what was fine art and what was applied art. In Jakarta they use painting in the street as communication. I don’t think you can say that painting, sculpture and graphics are fine art and other applied art is just decoration, advertisement, or craft….

I was very experimental which was rejected by my teachers because I used elements from ‘low’ art. For example, Aquarium: I questioned the use of water – not just to mix colours but to use water as a means of expression. Since I used a container for the water, I called it ‘Aquarium’.”[39]Interview, Yogyakarta, 31/05/2002

From the very beginning Heri was resisting any limitations being applied to the style, media or references that he could use as a means of creating art, moving conceptually from prioritizing the medium to prioritizing the idea being expressed. He has continued to resist any form of compartmentalization including definitions by art theory. This is indicated by the notes on the invitation for his solo exhibition at Cemeti Art House in 2001, titled Disekitar Jebakan/ The Trap’s Outer Rim. The ‘traps’ he considers are visual and conceptual obstacles for the artist and, he asks,

“… is the artist caught by these traps and therefore returns to conservative… assumptions: for example, Wayang represents tradition whereas paintings are modern and installations are contemporary?”[40]Artist’s statement for the invitation to Heri Dono, Disekitar Jebakan/ The Trap’s Outer Rim, 9 November – 6 December, 2001, Cemeti Art House

He was challenging conventional distinctions that create a dichotomy between the traditional art/crafts and the modern.

Heri and Nindityo Adipurnomo were friends in their student days at ISI and, since neither the existing commercial galleries nor the college system encouraged the exhibition of their work, they were both forced to seek alternative outlets. Critics, most of whom were or had been painters and some of whom were his teachers, dismissed his work as kitsch and not serious.[41]Wiyanto, H., and Nadi Gallery, 2004, Heri Dono, Jakarta, Indonesia, Nadi Gallery, p.96 Heri’s rebellion culminated in his dropping out of ISI in 1987 after seven years and just months before graduation because he considered becoming an artist should not be dependent on writing a thesis for a degree. He had been speaking with older artists who had established themselves without academic qualifications, and he said

“There is no guarantee that you will become an artist if you graduate so I decided to become an artist for myself.”[42]Heri Dono, interview, Yogyakarta, 31/05/02

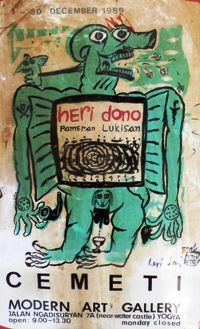

When Nindityo and Mella opened Cemeti in January, 1988, the first exhibition was a group show with Heri, Eddie Hara, Harry Wahyu and themselves. [43]Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, 1988-2003, Yogyakarta, Chronology of exhibitions / events at Cemeti Art Gallery 1988 – 1999 and at Cemeti Art House 1999 … Continue reading It was followed in March by the first solo exhibition held in Cemeti of Heri’s work, and Heri exhibited with them again in December 1989. In those early years Heri and Cemeti were mutually supportive:

“I exhibited there because I wanted to support the alternative gallery. I was interested in their perception of art and in creating a community, not just following the senior artists.”[44]Interview, Yogyakarta, 31/05/2002

Both the newly established gallery and Heri’s career received a boost from the sale of work by Mella and Heri to an American architect and this, combined with a loan, allowed Heri to finance a residency in Basel, Switzerland, in 1990. Cemeti had helped Heri survive when there was no market for his performance and installation work but, after Heri returned from overseas, Mella felt he was seeking prices for his work that were European-based and not realistic in the Indonesian market. Thereafter Heri’s opportunities to exhibit diversified considerably and he did not join with Cemeti again until the inaugural exhibition, Knalpot, at the new Cemeti Art House, May – July 1999.

Although his relations with Cemeti remained amicable, Heri felt that it had ‘become elite’ and he did not want young artists excluded from exhibiting there to believe he was part of Cemeti’s ‘stable’. Their ongoing relationship was confirmed by a major solo exhibition Heri held at Cemeti in December 2001, an exhibition that was in part an important retrospective.[45]Interview, Yogyakarta, 31/05/2002

Although Heri Dono held solo exhibitions and participated in many group shows internationally every year since the 1980s, initially his work did not receive the same support at home. This was the common reaction to experimental contemporary art in Indonesia at the time and is illustrated by Astri Wright’s description of Heri’s solo exhibition in Jakarta in June, 1988. Wright reported that no Indonesian critic reviewed the exhibition and no works sold until her review was published in the English language Jakarta Post. Then nine of the ten small works that sold were bought by foreigners, a further indication of their appeal to overseas rather than local collectors at that time.[46]Wright, A., 1994, Soul, spirit, and mountain preoccupations of contemporary Indonesian painters, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, footnote, p. 238. Ibid

Heri was selected for the exhibition, Modern Indonesian Art, Three Generations of Tradition and Change, in America in 1990, for which Wright was one of the curators. Being the first major survey exhibition of Indonesian modern art outside Indonesia, this was a significant exhibition. Each step outside Indonesia contributed to his career, raising his profile and compounding his value as an artist. Articles written about his work assisted in his gaining overseas residencies that as well as the environment for making work, provided the opportunity to network and develop influential contacts. His first residency was in Basel, Switzerland, then Oxford U.K., followed by a number of residencies in Australia including ones in Canberra, Townsville, Melbourne and Brisbane; then Vermont, USA, Vancouver, Canada, and Singapore.

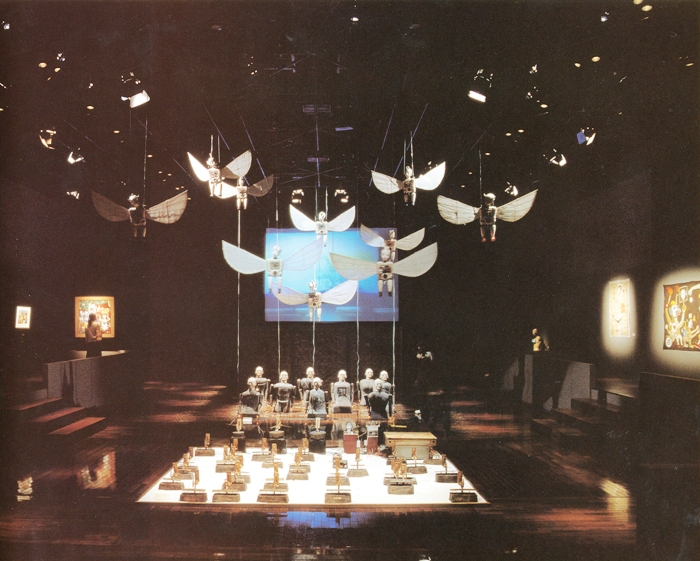

An indication of the value of contacts in the international circuit is seen in Heri’s relationship with David Elliott, then Director of the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, England. Elliott first saw Heri’s work at APT/1 in 1993 and two years later invited Heri to go to Oxford on a three-month residency. Elliott co-edited the catalogue, an illustrated book, for the exhibition that resulted from the residency.[47]Elliott, D. and Gilane Tawadros, eds., 1996, Heri Dono, Oxford, Institute of International Visual Arts, London in association with the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford Subsequently Elliott became Director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and then Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum and continued being a director of major survey exhibitions. Therefore Heri’s art was well known to a major player in the international and, in particular, Asian art circuits and Elliott contributed an essay to Heri’s major retrospective exhibition for the Japan Foundation Asia Center in 2000.[48]See David Elliott, “Dono’s Paradox: the Arrow and the Kris” in Yasuko, F., ed., 2000, Heri Dono: Dancing Demons and Drunken Deities, Asian Contemporary Artist Solo Exhibition Series 1, Tokyo, … Continue reading

Heri’s work began to be bought for public collections from The Hague to Tokyo and the interest of Indonesian collectors was aroused when Dr. Oei Hong Djien bought an early painting of Heri’s titled, The Suppressor, (Orang Injak). ‘Pak Doktor’, being one of the leading investors in art and having a major collection of art in his museum in Magelang, Central Java, investors watched what he chose. While Heri’s installations appealed to institutions, his paintings were more marketable and they began to sell for high prices in Indonesian auction houses and galleries. By 2002 the art market was exploding and collectors clamoured to buy his works, When Nadi Gallery held his exhibition, they ran a lottery not for the works but just the right to purchase the works.[49]Hendro Wiyanto, in an email to Yuliana Kusumastuti, in Kusumastuti, Y., 2003, Market Force and Contemporary Art Practice in Indonesia, draft Master’s thesis, Faculty of Law, Business and Art, … Continue reading) Overseas galleries also began to express interest in representing him, among them the Sherman galleries in Sydney, Australia.

An advantaged position begets further advantages and Heri has been able to live by making art since he left art school, travelling the world mounting exhibitions, giving performances and participating in international events. In just three months, between June and September 2003, Heri visited Venice to install his work at the Venice Biennale, then he travelled to Semarang, Central Java, for a solo exhibition, Melbourne, Australia, for the Australian Print Workshop, Niigata, Japan, for the 2nd Echigo Tsummari Art triennial and Jakarta for the first CP Open Biennale.[50]Bianpoen, C., 2003 “Heri Dono achieves new milestone”, Jakarta Post, Jakarta, July 10, 2003 One of Heri’s friends commented in amazement: “Thousands of miles without jetlag!”[51]Quoted in Dirgantoro Wulandani, 2006 “Thousands of Miles without Jetlag – Heri Dono’s Travels”, Solo exhibition, Heri Dono: The Broken Angels, Gertrude Contemporary Art Space, … Continue reading All of these activities established his credentials and brought him to the attention of international curators, researchers and writers. If Jim Supangkat was the international face of Indonesian art curatorship in the 1990s, then Heri Dono became the international face of Indonesian contemporary art.

According to Heri the most important invitation to exhibit was from the Asia Pacific Triennial in 1993

“… that was my passport to international exhibitions”[52]Interview, Yogyakarta, 31/05/2002

He also performed with the Elision Ensemble in APT/3 1999, and, in 2002 in APT/4, he was the only artist from Indonesia who was exhibited. APT/4 marked a change in the Asia-Pacific Triennial format for the initial funding for the APTs had ended, many of the original curatorial staff had left and the Queensland Art Gallery was building a major extension for their contemporary collection, the Gallery of Modern Art, or GoMA. APT/4 was an exhibition-in-depth of work mainly from their collection from a few of what were considered to be ‘landmark Asian and Pacific artists’.

In 2003 the Biennale Director, Francesco Bonami, and the curator, Hou Hanru, personally invited Heri Dono to exhibit in the Venice Biennale, he being the only Indonesian artist to be invited since Affandi in 1954. Being invited by the organizers to the Venice Biennale is a greater honor than exhibiting in satellite exhibitions mounted by individual countries around Venice or in the pavilions of the Giardini gardens.

Heri Dono has also exhibited twice in the Sao Paulo Biennial: first in 1996, curated by Jim Supangkat, and then in 2004. Other exhibitions for which he has been selected include the Asian Art Show in 1994, which later became the Fukuoka Triennial, the first Gwangju Biennale in 1995, the Traditions and Tensions exhibition in 1996, and the Shanghai and Havana Biennales in 2000. The Sydney Biennale, with its Eurocentric bias, has not been famed for exhibiting modern Asian art apart from that of Japan. Affandi was chosen for exhibition in 1973 but thereafter no Indonesian has exhibited until Heri Dono and Brahma Tirta Sari were invited in 1996, and none since. Stephanie Britton, writing in the Artlink magazine, identified “The 112 most invited artists across 64 editions of the biennials on the map 1993 – 2006 according to the number of gigs for each artist”. Heri Dono had 8 ‘gigs’, only one less than the three most exhibited artists: Yang Fudong, Cai Guo-Qiang and William Kentridge. [53]Britton, S., 2005 “Biennials of the world: myths, facts and questions”, Artlink (Australia), Vol. 25 no. 3, pp.34-37

It is not difficult to see why Heri Dono’s work was selected so often for he met the interests and criteria of the curators of international exhibitions and has continued to do so with inventiveness and a playful sense of humour. His works refer to the socio/political conditions from which he springs and Indonesian traditions that are exotic to an international audience and his media and installations are compatible with the artistic vocabulary of global exhibition.

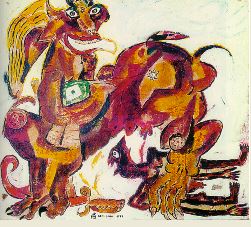

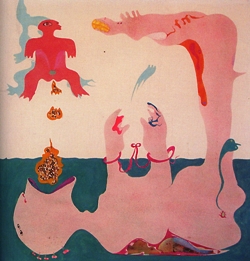

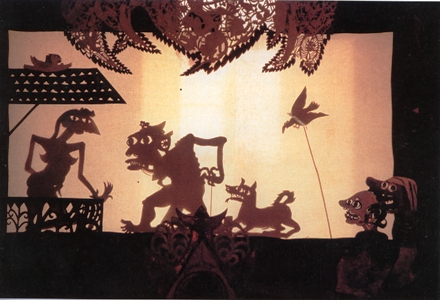

His early painting while at ISI diverged from the popular art style at the time, the photographic realism represented by the work of artists like Dede Eri Supria. Although Heri shared Supria’s socio/political commitment, he rejected the formal style, experimenting instead with cartoon images from television mixed with multi faceted images from the Wayang. Heri was attracted both to cartoons and the Wayang for their illogical and fantastic inventions:

“A chair can get up and run, a drop of water can smile, a tree can dance or even fly”, he said. But “….a character is shot full of holes and then drinks a glass of water which spurts out. These are not dreams, it happens in the media.”[54]Quoted from Heri Dono, “Watching the Logic through an Upside-down Mind” in Yasuko, F., ed. 2000 ibid, p.82, and Tim Martin, “Heri Dono Interview”, in Elliott, D. and Gilane Tawadros, eds. … Continue reading

For Heri the real world of Indonesian politics can be as unreal and illogical as cartoons because it turns truth inside out and upside down.

Heri Dono, being the product of a modern art school education, adds Picasso and Miro to this mixture of influences and the permission their art gave to dismember and distort. The Dadaists inspired his interest in performance art and their rejection of aestheticism in favour of social and political protest.[55]Pausacker, H., 2006 “Whimsical protest Transforming rubbish into political art”, Inside Indonesia, p.23 Indonesian artists and art writers, though, resist the definition of Indonesian art in terms of influences from Western Modernism, and Jim Supangkat, writing about Heri Dono in terms of art theory, argues for the need to develop a local discourse to counter the dominance of Western theoretical positions.[56]Note Supangkat’s discussion in “Context”, in Yasuko, F., ed. 2000 ibid, pp.102-104 Heri combines all branches of the arts in his work, both traditional and modern, mixing, for example, animation and animism and creating a unique composite form. If the work is defined in the terms of Western Modern art influences alone, his local references may be overlooked and his creative combinations devalued.

Homi Bhabha, in discussing cultural hybridity in a postcolonial context, coined the phrase ‘the Third Space of enunciation’. He wrote,

“It is that Third Space… that ensures that the meaning and symbols of culture have no primordial unity or fixity; that even the same signs can be appropriated, translated, rehistoricized and read anew.”[57]Bhabha, H. K., 1994, The location of culture, London; New York, Routledge, p.37

Heri Dono’s work has been analyzed by a number of writers in terms of this and similar theories. In his essay, “Heri Dono: Bizarre Dalang, Javanese Bricoleur, Low-Tech Wizard,” the Thai curator, Apinan Poshyananda, discussed Heri’s work in terms of bricolage, or combinations of materials that come to hand. Heri’s creativity, he considered, should be recognized as subverting and re using Indonesian traditions, saying, “….his bricolage can imply the creation of new signs and the breaking open of already existing signs”.[58]Poshyananda, A. 2000 “Heri Dono: Bizarre Dalang, Javanese Bricoleur, Low-Tech Wizard,” in Yasuko, F., ed., ibid, p. 86. The term, ‘bricoleur’ was first coined by the anthropologist, … Continue reading

Hendro Wiyanto, in his detailed discussion for the catalogue of Heri’s exhibition at Nadi gallery in 2004, refers to Heri’s appropriations as a Postmodern, Baudrillard-ian simulation[59]Wiyanto, H. and Nadi Gallery, 2004 ibid, p.47. Baudrillard’s Simulacra, the deconstruction of meaning, copies of copies without originals is, though, ultimately nihilistic.[60]Note the discussion of nihilism in Baudrillard’s concepts in Gablik, S., 1988 “Dancing with Baudrillard,” Art in America, 76, (6): 27-29 Heri, on the other hand is positive about the meanings in his references, believing their meanings and even their underlying meanings, if negative, can be changed. Baudrillard’s nihilistic game playing is at odds with artists who are committed to raising awareness and seeking to change society. If the message coming from the politicians seems sweet but is in fact a distortion, Heri believes his whimsical, fantastic creations will identify what is false for the audience and empower them for change. What is significant here is the rare attempt to frame Heri’s work in terms of Postmodern theory by the writer/curator, Hendro Wiyanto, who has studied philosophy. Other Indonesian artists are rarely subjects for theoretical analysis, but Heri, now with an international profile, was attracting serious attention.

An early work, Eating Shit, (Makan Tokai), uses Miro-like whimsical shapes floating and changing like amoeba, in a flat space of pastel pinks and teal greens. The colors are reminiscent of a Matisse palette and suggest pleasure and relaxation which is strangely at odds with the scatological subject. Heri had learned that dissidents held in custody had been forced to eat their own excrement and so there is an edge, anger even, beneath the simulated pleasure of his image. The title subverts the playfulness, the fantastical become grotesque and the messages coming from the powers controlling public life are undermined by the possibility of alternative meanings. Most of Heri’s future work will contain in varying degrees similar contrasting elements: humour and horror, playfulness and criticism, comedy and tragedy.

Heri was well aware of the ‘double speak’ publicly used by the regime. He wrote:

“It was particularly difficult to distinguish reality from falsehood through the mass media or through educational institutions, particularly under the Suharto regime….the favourite expression of the power holders was: ‘In the interest of National Stability’. In this fashion life became increasingly convoluted.”[61]Heri Dono, “Watching the Logic through an Upside-down Mind” in Yasuko, F., ed., 2000, ibid, p.82

Open discussion was not permitted and Suharto’s repression made avoidance of confrontation necessary. Heri has a very Javanese way of expressing resistance, both to his art education at a personal level and to violence perpetrated by the state: the nice surface and the bite beneath.

As with most of the alternative artists in the 1990s, art for Heri is grounded in social and cultural issues, as he said, “Art always concerns human values and, necessarily, culture.” Heri has repeatedly stated his involvement with marginalized people and has worked with gravediggers, becak drivers, street children and the collectors of rubbish, but he rejects sympathetic depictions of the poor. He said, “Representing a homeless person on canvas does not solve any human problem….the issues to be tackled by art are not aesthetic questions….but rather questions outside art…”.[62]Heri Dono, May 2 1986, quoted in Wiyanto, H. and Nadi Gallery, 2004, Heri Dono, ibid, p.112

In his installation, Blooming in Arms, at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, in 1995, Heri expressed criticism of government policy, big business and militarism through large military figures of mesh entwined with greenery. His anger was aimed at the hypocrisy of a program called Penghijauan, the ‘greening’ of Indonesia by encouraging people to plant trees in their gardens while Kalimantan, Sumatra and Irian Jaya (now West Papua) were being deforested. “What kind of equality is this if you plant one tree in front of your house while one thousand trees in the forest are cut down?”[63]Elliott, D. and Gilane Tawadros, eds., 1996 ibid, p.22 A review of the exhibition published in the The Times in 1996 drew a response from the Indonesian Embassy in London. They disputed the criticisms of the regime expressed in Heri’s exhibition catalogue and demanded that it be withdrawn with a threat that otherwise Heri’s return to Indonesia could be made difficult. The catalogue is still unavailable for this reason.[64]David Elliott, “Dono’s Paradox: the Arrow and the Kris”, in Yasuko, F., ibid, p.109. According to the Institute of International Visual Arts, INIVA, the catalogue cannot be purchased, … Continue reading

Heri has at times denied he is political even though there is now greater freedom of expression since the downfall of Suharto. He said, “where politics are concerned I keep my distance. I am an artist, I know my position.”[65]Interview, Yogyakarta, 31/05/2002 This should be interpreted to mean that although he addresses socio/political issues in his own culture, he does not belong to any political party. When we met in March 2006, he was wearing a red T-shirt with an image of Megawati Sukarnoputri on it. He said he had hoped that the situation in Indonesia would improve when she was made president, but ‘nothing happened’ and now he just wears the T shirt because he has it.

Heri uses the street language known in Yogyakarta as plesetan, wordplay that can express criticism without giving offence, to undermine the ‘twisted logic’ of political pronouncements, strategies that are both subversive and liberating for powerless people.[66]Plesetan, from pleset, to slip or slippage. For an analysis of its linguistic base and usage in a political context, see Heryanto, A., 1999 “Where Communism never dies Violence, trauma and … Continue reading Indonesian society has complex hierarchies which are reflected in the different levels of language used in Javanese and in bahasa Indonesia, such as the formal deferential language for important people senior to the speaker, or colloquial speech between equals – codes that have to be learned for the subtleties of communication.

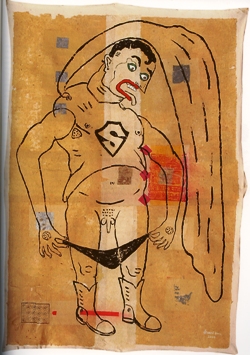

His verbal and visual puns can be seen operating in Superman Learning How to Wear Underwear, an image Heri has kept in his home, amused that a Superman is so stupid he wears his underpants outside his costume. One of Heri’s favourite characters is Semar, a god from the Indian epic, the Mahabharata, the basis of the legends in the Wayang. Semar is a super hero in the form of a lower class clown whose weapon is a fart. The character is a composite of opposites: he can be she, s/he is wise but a joker and someone who when drunk, can be turned into a devil and exploited by the authorities.[67]Irvine, D., 1996, Leather gods & wooden heroes : Java’s classical wayang, Singapore, Times Editions. Semar “…knew the will of the gods and the ways of men”. His character is … Continue reading In Heri’s work Semar becomes Supersemar or Superman or semar mendem, a local cake whose name means ‘the drunkenness of Semar’. “The leaders of government when speaking on TV may appease the masses with their wisdom and sweet charm but their abuse of power belies this sweetness. I used to eat the cake but now I perform it”, he said.[68]Heri Dono, “The Game”, 20 October 1995 in Elliott, D. and Gilane Tawadros, eds., 1996, ibid, p.21 Su-per-se-mar can also be an acronym, acronyms also being common in bahasa Indonesia, for the decree of March 11, 1966, when Sukarno signed over powers to Suharto: Su…surat or letter, Per…perintah or order, Se…sebelas or eleven, Mar….Maret or March.[69]Heri Dono, Interview with Apinan Poshyananda, New York 22/04/2000 in Apinan Poshyananda, “Heri Dono: Bizarre Dalang, Javanese Bricoleur, Low-Tech Wizard”, in Yasuko, F., ed., 2000, ibid, p.89