Artists were affected by and often closely involved with Reformasi and their artworks provide an important insight the events of 1998.

In 1996 the work, Plastic Happiness, by the Korean artist, Choi Jeong-Hwa, was exhibited in Contemporary art in Asia: traditions, tensions, mounted by the Asia Society New York. When the exhibition travelled to other sites, it was often shown at the entrance and was the first work to be encountered by visitors. It was a huge, yellow, plastic pig with a red money bag on its back. The pig, a symbol of prosperity for many cultures in Asia, inflated and collapsed like a giant fairground balloon in a comic and grotesque fashion. But ultimately it was disturbing, for it was a premonition of the financial crisis that was about to hit Asia. It is an example of the way in which international survey exhibitions often reflected the mood and tensions of the time.

The following year, 1997, was pivotal both for Indonesian art and politics as Indonesia teetered on the edge of seismic change after 30 years of President Suharto’s autocratic rule. The Asian financial crisis, known in Indonesia as Krismon (from krisis moneter or monetary crisis), triggered instability in a regime that was rife with corruption, and it was the final element to tip the protest movements for Reformasi over the edge into revolution.The government could now no longer control inflation. The rupiah devalued steeply: at the height of the crisis the rupiah lost most of its value against all other currencies, devaluing sevenfold in relation to the US dollar from Rp 2,500 to Rp 17,000.[1]Ricklefs, M. C., 2001, A history of modern Indonesia since c. 1200, Stanford, Calif., Stanford University Press, p. 404. Indonesia had been known as a rising ‘Asian Tiger’ economy, but the corrupt and nepotistic Suharto government had monopolised resources and manufacturing so while there had been an appearance of economic prosperity, it had been built on debt and “when the bubble burst, as indeed it did, political and economic turmoil followed.”[2]Mark McGillivray and Oliver Morrissey, “Economic and financial meltdown in Indonesia: prospects for sustained and equitable economic and social recovery”, in Budiman, Arief, Hatley, … Continue reading Unemployment escalated out of control, prices rose rapidly and suddenly more people, both in the cities and in the country, were pushed below subsistence levels.

One of the first demonstrations was by Suara Ibu Peduli, the Voice of Concerned Mothers. In February 1998, in front of Hotel Indonesia in Jakarta, they demanded affordable milk as the rising prices were depriving children of essential food. It was organized by a small group of university alumni, including Professor Toety Heraty, who were protesting amongst other things the government’s masculine paradigm of power that had brought about this economic disaster. Despite presenting themselves in the traditional roles for women with the interests of the family at heart, the police interrogated and threatened them. The Demo Susu, the demonstration for milk, gained much publicity and later they extended their activities to supporting student activists and victimized women.[3]Oey-Gardiner, Mayling and Bianpoen, Carla, 2000, Indonesian women: the journey continues, Canberra, Australian National University, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, p.286.

The political leaders and the military met the mounting protests in their typical repressive manner and were “…unwilling to countenance significant political changes, in particular towards democracy”. The rising tide for reform led to widespread rioting.[4]Budiman, Arief, Hatley, Barbara, et al, 1999, Reformasi: crisis and change in Indonesia, Melbourne, Monash Asia Institute, p.18.

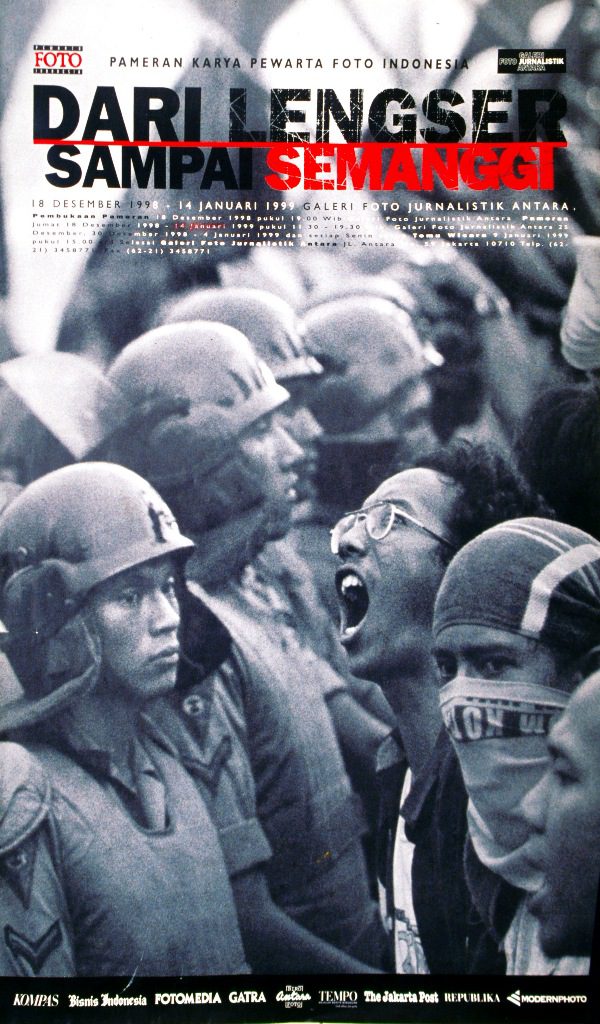

A poster photographed in the tiny studio of Nandang Gawe, a Bandung artist, expressed all the pent up frustration the students and activists felt at the time. Student-led demonstrations from many campuses erupted across Java in 1998 and “…played a key role in transforming the economic collapse and the political malaise into a full-blown political crisis”.[5]Edward Aspinall, “The Indonesian student uprising of 1998”, in Budiman, Arief, Hatley et al. 1999 Reformasi, ibid, p.212. During a demonstration on May 12th, four students from the private and elite Trisakti University were killed, which shocked and galvanised the nation. Clashes followed between vigilantes and student groups in street battles. These culminated on November 13th at the Semanggi intersection near parliament house when troops opened fire, killing seven students and injuring hundreds of protesters.[6]David Bourchier, “Skeletons, vigilantes and the Armed Forces’ fall from grace” in Budiman, Hatley, et al. 1999, Reformasi, ibid., pp.158 – 159. Students were targeted by the security forces and some students were abducted and ‘disappeared’.

Artists working with social and political issues were roused to action. Titarubi made an artwork in response to the targeting of students titled, Missing and Silent, which was exhibited at Galeri Lontar, the exhibition space of Komunitas Utan Kayu in Jakarta, as part of ‘Earth Day’ in 1998 by the Alliance for Better Earth and Human Life, for which Tita was an organizer.[7]Titarubi was originally referred to me as Dwi Puspita, but in recent years she has been exhibiting as Titarubi and is generally known as Tita.

Tita’s artwork was in response to the disappearance of twelve student activists who had been taken by the military and never seen again, although other detainees had heard them in the prison. Tita wanted to shock people out of perceiving the loss of these young men as just a statistic and personalize the experience of victims, as Dadang Christanto had aimed to do in his work. She hung twelve bags of water from the ceiling, each containing a foetus made out of wax, the foetus being important to her as a mother, and the bags of in Bandung. Over the period of the exhibition the foetuses dissolved in the bags and disappeared.[8]Interview, Tita, Yogyakarta 16/07/01.

Tita had been an activist since her student days at Institut Teknologi Bandung or ITB and was one of the volunteers who provided support for political detainees in prison, including the playwright and director, Ratna Sarumpaet. After the murder of the union worker, Marsinah, in 1993 in Surabaya, Sarumpaet had written, Marsinah: Nyanyian dari bawah tanah, Marsinah: a song from the underworld. She repeated the reference to Marsinah in a monologue in 1998 titled, Marsinah Menggugat, or Marsinah Accuses, as a political protest against the rigged re election of Suharto for another 5 year term. Sarumpaet was imprisoned for ‘unacceptable political activity’ and was one of the last to be jailed under the crumbling Suharto government.[9]http://www.insideindonesia.org/content/view/767/29/ The history of the worker, Marsinah, is recounted in the previous chapter in relation to Moelyono’s exhibition. For Ratna … Continue reading

Madness broke out in many cities across the nation, culminating in the worst day of rioting in Jakarta on May 14. Homes and businesses were invaded and torched with many deaths occurring when bystanders and looters were trapped inside, particularly in burning supermarkets.

FX Harsono reported that soldiers were seen standing on a bridge watching as rioters looted a Chinese supermarket below.[10]FX Harsono, personal conversation, 26/6/01. This was an indication that throughout the mayhem, the role of the police and soldiers was at best questionable and at worst contributory, for some militias were involved in assisting or even organizing mob violence. It appeared that the military, by fermenting trouble and then quelling it, were attempting to prove they were necessary to re establish order and were reinforcing their power base in the crumbling political environment.

Semsar Siahaan, who had refused an invitation to exhibit overseas and a residency so that he could be part of the rising tide of Reformasi, was targeted again and his house in Jakarta was ransacked by the military. He walked out, leaving his house open to looters, and eventually immigrated to Canada from Singapore.

Harsono, an ethnically Chinese Indonesian, was worried for his daughter who was two hours late returning from school as rioting was close and a bank nearby had been burned. He set out in his car and fortunately found her safe, but the family stayed inside their home for two days in fear of local gangs.

The Chinese community was targeted as it has so often been in the past and reports emerged of the rape and murder of ethnically Chinese women that were so shocking, they were difficult to comprehend. Official enquiries met a wall of denial, the perpetrators benefiting from the reluctance of the victims to testify. Eventually statements were collected and the atrocities proven, but few have been prosecuted. The end of the Suharto era was marked by this now undeniable horror.[11]Numerous reports include: Gerry van Klinken, “The May Riots” and Susan Berfield and Dewi Loveard, “Ten days that shook Indonesia,” in Aspinall, Edward, van Klinken, Geert … Continue reading

These events deeply shocked the artistic community. Arahmaiani witnessed the rioting first hand and reported that she had “… stood among the bystanders in the night by looted stores and burning homes where charred or wounded bodies of Chinese-Indonesian women of all ages, many of them raped and tortured, were carried out.”[12] Astri Wright, based on communications with Arahmaiani, in “Thoughts from the Crest of a Breaking Wave”, in O’Neill, H., T., Lindsey, et al., 1999, AWAS! : recent art from … Continue reading

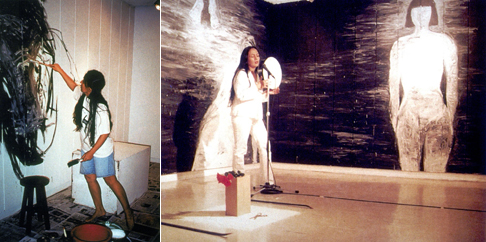

Arahmaiani translated this experience immediately into a performance entitled Show Me Your Heart, at the Nippon International Performance Art Festival, in Nagoya, Japan. Her performance was described as a ‘simple soliloquy of voice, hand- drum and slide projections of her drawings…'[13]Lee Wen, “The Asian performance art series,” 1999, Art AsiaPacific, April, p.82. In 1999 she developed the performance further for the conference/exhibition: Women Imaging Women: Home, Body, Memory, at the Cultural Centre of the Philippines, Manila, with her work titled, Burning Body-Burning Country 11. In a space surrounded by large brush drawings of figures, Arahmaiani gave a performance that she stated was ‘…for the souls of the women who were violated and killed last May in Jakarta, or who committed suicide afterwards.’ Astri Wright witnessed the performance in Manila and gave a detailed description, and on both occasions it was reported the audience was profoundly moved.[14]Datuin, F. M. V. and Flores, P. D., 1999, Women imaging women : home, body, memory : papers from the Conference on Artists from Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, Cultural Center of … Continue reading

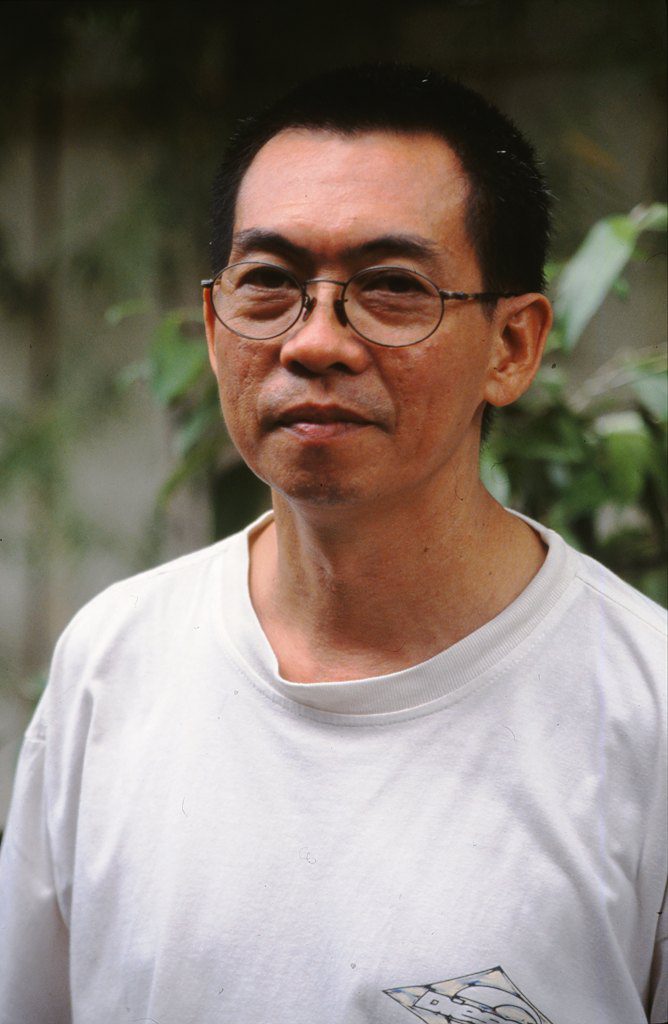

It would not be too strong to describe Harsono as having been traumatized by these events. He was bitterly disillusioned that the underprivileged people he had worked for and empathized with had turned against the Indonesian Chinese.

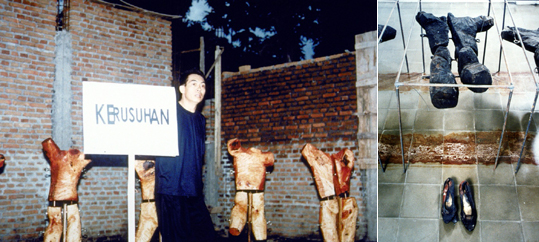

A performance he gave at Cemeti Art House in Yogyakarta on October 18th illustrated his distress. The performance titled, Burned Victims, was inspired by the report of a shopping mall which was sealed and set on fire during the riots, trapping many people inside. He burned life sized wooden torsos and held aloft placards which read: Riot, and Who is responsible? The scorched torsos were then stretched on frames in the gallery where the remains conveyed a sense of violation and pathos, burnt shoes placed beside them on the floor the last sign of their humanity.

After this he was unable to make art work. He told me in 2000:

“I haven’t made artwork since 1998 because I feel so upset. So I work for a voluntary organization caring for women who were raped or attacked in the riots. I am a Catholic so I pray ‘Our Father who art in heaven…’ and it seems I must forgive, but it is difficult. I can’t forgive the people who did this…”

When he did return to his work, his disillusionment about genuine democratic reform and shock from the attacks on the Chinese community resulted in his art becoming more introspective. He said:

“Now after Suharto I started to see a different situation… I am in a transitional period… A lot of people can make social and political work to criticise the government – I must look back to my position in the art itself.”[15]FX Harsono, interview, 26/06/01.

Now, when other artists felt free to express their opinions and jump on the political art bandwagon, Harsono turned inward. Later, in explaining the different direction his work took, he said,

“I felt I had lost my orientation on morals, ethics and even nationalism. If they were all still being voiced, I felt them as empty slogans with no meaning at all”.[16]Singapore Art Museum catalogue, FX Harsono: Testimonies, 4 March to 9 May, 2010, p. 40.

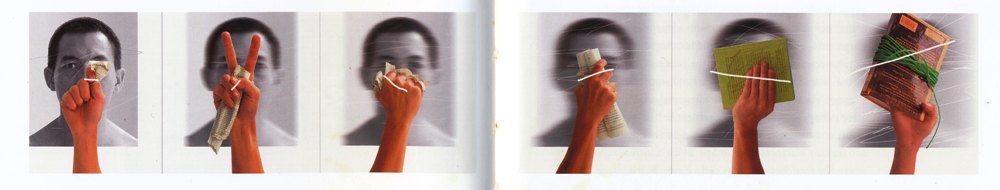

He began a series of photo-etch print works where he explored his own uncertainty about who he is and the purpose of his work. Amongst his first works was Cogito Ergo Sum, (Descartes’ ‘I think, therefore I am’), where he depicts himself frontally, as if for a formal identity document, but increasingly erased by a hand holding the pages of a book until only the book remains in front of a blurred image. It is uncertain what the book is but we are left with a sense that Harsono is being defaced and removed from some official public identification without knowing what it is and what he has become.

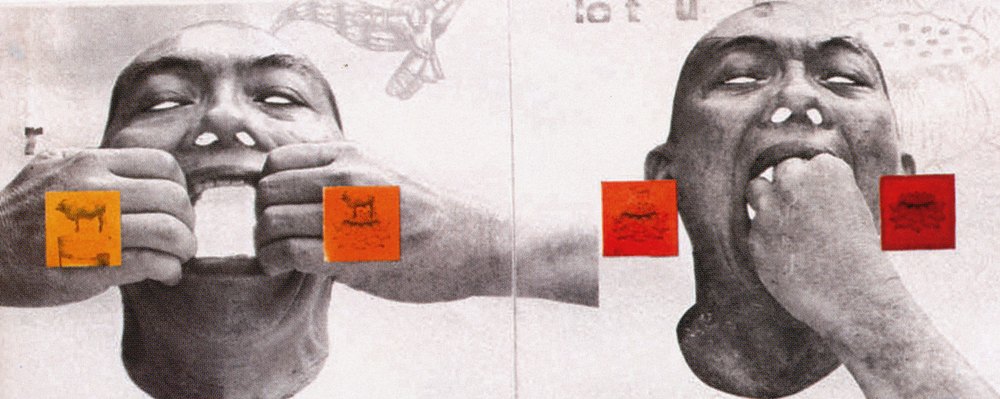

He continued to use his own image in his work, but in a deconstructed way so that he represented people in general rather than a personally expressing himself. In another work, Open your mouth, his face is blank and there is nothing behind his eyes and mouth. He said that this represented the situation in Indonesia at the time: everyone was speaking, everyone opened their mouths, but nothing of any import came out.[17]Harsono speaking at Gallery 4A, Sydney, 18/02/2012. He added ambiguous symbols that were disturbing because their meaning was unclear: the lotus as a general symbol for religion and a barking dog which seemed to refer to an Indonesian saying, ‘carry on and ignore the barking dog’, but who was the barking dog? He makes visual his disillusionment amidst the confusion of post Reformasi and the painful process of seeking meaning.

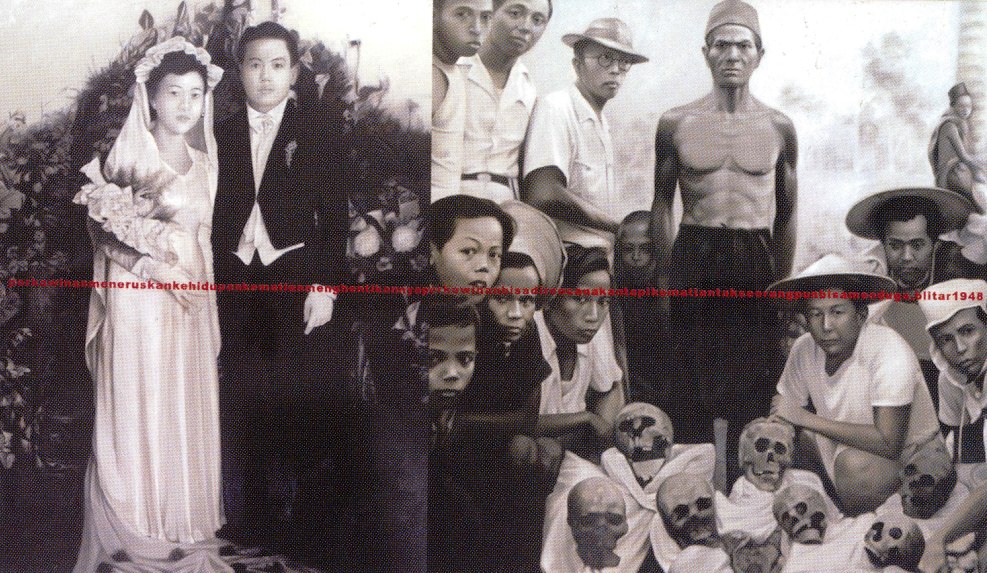

In the decade following 2000, Harsono returned to explore his ethnic history, beginning with photographs left to him by his father who had a photographic studio in Blitar. His father was commissioned by the Chinese community organization, Chung Hua Tsung Hui, to document the disinterment of Chinese Indonesian remains from a massacre that occurred in Blitar in 1948. Harsono has used some of his father’s original photographs and linked the personal history of his family to the victims by the title of the work, Preserving Life, Terminating Life. A diptych shows a marriage on one side and the skulls on the other. The images are black and white, documentary style, but a red thread, a significant colour in Chinese culture, stretches across the canvases, linking the two. These works were the beginning of his own research into the experiences of the families and witnesses connected to the massacre, which he has also documented in a video.[18]The video is titled nDudah, Javanese slang for digging up, and can been seen on Harsono’s website:http://www.fxharsono.com/video.php

By 2007 Harsono had developed a vocabulary of enigmatic symbols, needles and butterflies as victims, with which he identifies. These featured in a retrospective exhibition held at the Singapore Art Museum in May, 2010, titled, FX Harsono: Testimonies. Belatedly Harsono’s work has attracted international attention and by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, he too had a global career with particular recognition in Asia.

Suharto’s New Order regime collapsed like a house of cards in three brief months between February, when the rupiah hit an all-time low against the US dollar, and May 1998, when protest exploded into riots. The DPR, Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, The People’s Representative Council, was occupied first by students and then by many others who joined them. On May 21 Suharto stepped down but was replaced by his vice-president, Habibie, which many found suspiciously like a means of maintaining the status quo. Social, economic and political confusion continued and religious and ethnic violence broke out across the archipelago, particularly in Aceh, Ambon and Timor.

References

| ↑1 | Ricklefs, M. C., 2001, A history of modern Indonesia since c. 1200, Stanford, Calif., Stanford University Press, p. 404. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mark McGillivray and Oliver Morrissey, “Economic and financial meltdown in Indonesia: prospects for sustained and equitable economic and social recovery”, in Budiman, Arief, Hatley, Barbara, et al., 1999, Reformasi: crisis and change in Indonesia, Melbourne, Monash Asia Institute, p.16. |

| ↑3 | Oey-Gardiner, Mayling and Bianpoen, Carla, 2000, Indonesian women: the journey continues, Canberra, Australian National University, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, p.286. |

| ↑4 | Budiman, Arief, Hatley, Barbara, et al, 1999, Reformasi: crisis and change in Indonesia, Melbourne, Monash Asia Institute, p.18. |

| ↑5 | Edward Aspinall, “The Indonesian student uprising of 1998”, in Budiman, Arief, Hatley et al. 1999 Reformasi, ibid, p.212. |

| ↑6 | David Bourchier, “Skeletons, vigilantes and the Armed Forces’ fall from grace” in Budiman, Hatley, et al. 1999, Reformasi, ibid., pp.158 – 159. |

| ↑7 | Titarubi was originally referred to me as Dwi Puspita, but in recent years she has been exhibiting as Titarubi and is generally known as Tita. |

| ↑8 | Interview, Tita, Yogyakarta 16/07/01. |

| ↑9 | http://www.insideindonesia.org/content/view/767/29/ The history of the worker, Marsinah, is recounted in the previous chapter in relation to Moelyono’s exhibition. For Ratna Sarumpaet’s Marsinah: Nyanyian dari bawah tanah, Marsinah: a song from the underworld, see Barbara Hatley, “Ratna Accused, and Defiant”, Inside Indonesia, No. 55, July – September 1998. |

| ↑10 | FX Harsono, personal conversation, 26/6/01. |

| ↑11 | Numerous reports include: Gerry van Klinken, “The May Riots” and Susan Berfield and Dewi Loveard, “Ten days that shook Indonesia,” in Aspinall, Edward, van Klinken, Geert Arend, et al., 1999, The last days of President Suharto, Clayton, Vic., Monash Asia Institute; and most recently, Purdey, J., 2006, Anti-Chinese violence in Indonesia, 1996-99, Singapore, Singapore University Press. Concerning the testimony of victims, see Dewi Anggraeni, “Exposing crimes against women”, in Aspinall, E., Klinken, et al. 1999, ibid, pp. 65 – 66. |

| ↑12 | Astri Wright, based on communications with Arahmaiani, in “Thoughts from the Crest of a Breaking Wave”, in O’Neill, H., T., Lindsey, et al., 1999, AWAS! : recent art from Indonesia. Melbourne, Indonesian Arts Society, p. 53, also http://eamusic.dartmouth.edu/~gamelan/javafred/rd_wright_awas2.htm accessed 19/04/07. |

| ↑13 | Lee Wen, “The Asian performance art series,” 1999, Art AsiaPacific, April, p.82. |

| ↑14 | Datuin, F. M. V. and Flores, P. D., 1999, Women imaging women : home, body, memory : papers from the Conference on Artists from Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, Cultural Center of the Philippines, March 11-14, 1999, Quezon City, Art Studies Foundation. The performance is reported from Astri Wright’s field notes, Manila, March 1999 in “Thoughts from the Crest of a Breaking Wave”, ibid, pp. 55 – 56. |

| ↑15 | FX Harsono, interview, 26/06/01. |

| ↑16 | Singapore Art Museum catalogue, FX Harsono: Testimonies, 4 March to 9 May, 2010, p. 40. |

| ↑17 | Harsono speaking at Gallery 4A, Sydney, 18/02/2012. |

| ↑18 | The video is titled nDudah, Javanese slang for digging up, and can been seen on Harsono’s website:http://www.fxharsono.com/video.php |