In the 1990s Indonesian socio/political art, which had a history dating from the independence movement, was the art most often chosen for international exhibition. It became a major outlet for expressions of dissent about internal conditions as the Suharto regime disintegrated.

By the beginning of the 1990s two distinct developments had become apparent in the Indonesian art world: one was the intense commodification of art, particularly of decorative painting, and the other was effectively its opposite, an experimental art that was critical of social and political conditions. It was this art that consistently seemed to be preferred by the selectors of international survey exhibitions.

Cemeti Art House shared a preference for experimental and socio/political art with the selectors for international institutions over the work of the older generation mainstream artists or the Yogyakartan Surrealists. Sudjana Kerton, A.D. Pirous, Srihadi Soedarsono and the Yogyakartan Surrealist, Ivan Sagito, for instance, were included in APT/1, but not thereafter, whereas Dadang Christanto and Heri Dono continued to be selected for later APTs and other international survey exhibitions.

Caroline Turner, then Deputy Director of the Queensland Art Gallery, co- founder of the Asia-Pacific Triennial Project and a selector of Indonesian art for the Asia-Pacific Triennial, justified the preference for socio/political art, saying:

“Clearly there is a lot of art in these countries which isn’t about the political or the social, and we have tried to document that to an extent, but I would argue that much of the most interesting art that is coming out of these countries deals with issues that are very much connected to changes taking place in these societies.”[1]Caroline Turner interviewed by Jennifer Moran for Pandanus Books, Newsletter, Spring 2005, issue 6, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, for the … Continue reading

Christine Clark, formerly the project manager for APT and also a selector of Indonesian artists, wrote:

“A review of the Indonesian selections in prominent international events during the mid and late 1990s illustrates a definite propensity to include artists whose work predominantly addresses overt political themes and who have already been seen in major exhibitions. The proclivity in these international events to select work addressing themes of political and social injustice was undoubtedly influenced by the possibilities that opened up for a great number of artists to focus on such themes during the fall of the New Order and subsequent Reformasi periods. However the near absence in international representation of other works, works that did not address such themes, does indicate the existence of an external force.”[2]Clark, C., 2003 “When the alternative becomes the mainstream: operating globally without national infrastructure”, in Cemeti Art House, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, … Continue reading

International exhibition was the outlet for activist art that had very limited support within Indonesia before the fall of Suharto. Ideological stimulation and some support came from NGOs that were a marked feature of social aid and political activity in the 1980s and 1990s, Moelyono, Harsono and Dadang Christanto all working for NGOs in their early careers.[3]Halim, H.D., 1999,. “Arts networks and the struggle for democratisation”, in Budiman Arief, B. Hatley et al ed., Reformasi: crisis and change in Indonesia, Melbourne, Monash Asia … Continue reading But it was overseas opportunities, exhibitions, scholarships and residencies that provided stimulus and allowed activist artists to construct a career. According to Caroline Turner,

“In many cases, exposure overseas was of great significance for them in legitimizing their role within Indonesia, in enabling them to meet with like-minded artists and intellectuals internationally, and allowing their work to reach a wider audience…”[4]Turner, C., ed., 2005, Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, Pandanus Books, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, p.211

Their art, in turn, provided an insight into socio/political pressures operating in Indonesia for curators who may well have shared their desire to raise awareness. Turner herself chose a work by Dadang Christanto for the image on the cover of Art and Social Change, Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, which she edited.

The work titled, 1001 Manusia Tanah/ Earth People, of 1996, was an installation of figures in the sea off Marina beach, Ancol, near Jakarta. They represented the poor who were powerless to resist being evicted for real estate developments and Dadang depicted them as pushed from their land into the water. Dadang would be selected for more than one Asia-Pacific Triennial and his career has directly benefitted from the association with Turner and the Queensland Art Gallery.

Activism versus Aesthetics

Much alternative art addressing socio/political issues has been described as ‘activist’, seeking to raise awareness, effect change andreach as wide an audience as possible beyond the educated and elitist audience of the art gallery.

Astri Wright described activist artists as aiming

“… to further heighten and stimulate awareness about important and problematic issues and to increase people’s will for active participation in social and political transformation.”[5]Astri Wright, 1999, “Thoughts From the Crest of a Breaking Wave”, AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia, catalogue, Hugh O’Neill and Tim Lindsay, (eds) Indonesian Arts Society, Melbourne, p. 49

Lucy Lippard, the American feminist, art critic, theorist and political activist considered that

“Art… may not be the best didactic tool available, but it can be a powerful partner to the didactic statement…”[6]Lucy R. Lippard, “Trojan Horses: Activist Art and Power”, in Brian Wallis, ed., 1984, Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, p.341

There has been an ongoing and significant debate in the West between those ardently committed to art serving political purposes and those who believe art can only serve artistic purposes. Those committed to the ‘art for art’s sake’ definition of Modernism charged political art with being nothing but propaganda and unable to effect any change. This denigrated propaganda as something that could never be artistic, yet from the beginning of the 20th century, Modernism had encompassed a reputable body of work that sought to harness modern art to political purposes. Russian abstract artists, such as El Lissitsky and the Constructivist, Rodchenko, sought to use their non- figurative art to support revolutionary causes, and left wing German Expressionists used their figurative and representational art to condemn social and political evils.

A similar debate occurred in Indonesia but, conditioned by the Suharto regime’s repression, attitudes to activist art were ambivalent if not actually contradictory. Always playing in the background was the memory of the horrors of 1965 which led to a fear of producing any work that was provocative or challenging and liable to being called ‘Komunis’. Halim, HD, an arts organizer from Solo, an area which had been designated as a cultural centre, described the attitude there as one of ‘political trauma’ and ‘politics phobia’. Halim suggests that some of these artists may also have been influenced by the Javanese tradition that defined the creative source of art as pulang, or divine inspiration and that art therefore should ‘pure’, free from social or historical processes.[7]Halim, HD, 1999, ibid, p.287 Then again, when priority is given to the content or message in a work of art, aesthetics and activism are driven further apart. As Asmudjo Irianto wrote, “…… works are often politically correct, but not aesthetically so”[8]Asmujo Jono Irianto, 2000, “An Unsettled Season, political art of Indonesia”, Art AsiaPacific, No. 28, p. 82. The conservatism of art education was also a contributing factor and many artists to this day, in a reaction to artistic priorities of their teachers in the art academies, will resist evaluation of their art on formal, aesthetic grounds.

Similarly an ambivalent relationship can exist between activist artist and the art market. Activist art is considered to critique the concept of art as a commodity and demand that art has a greater significance than decoration. Following a travelling exhibition of his works in 1988, Semsar Siahaan publically burned a considerable number of his drawings in an action he called Monumental Happening, Art Against Private ownership of Creative Works. Brita Miklouho-Maklai reported that ‘social activists accused him of artistic egotism’, that greater value would be had in keeping the works for the benefit of society, and that anyway, his action would ‘increase the value of his paintings to investors’.[9]Miklouho-Maklai, Brita, 1991, Exposing Society’s Wounds: Some Aspects of Contemporary Indonesian Art since 1966, Adelaide, The Flinders University of South Australia, Discipline of Asian … Continue reading

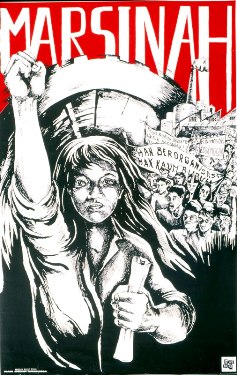

Yet in a society where there is extremely limited support for non-commercial art, if activist artists can sell their work, as Djoko Pekik did with his Celeng series, it is hard not to congratulate them for any manner in which they can survive. Both Djoko and Semsar worked in a figurative expressive style intended to communicate emotion and ideals more easily to the Rakyat, or man on the street. Semsar created iconic images that have circulated freely, such as the poster from his painting for the murdered worker activist, Marsinah. But the criticism of artistic egotism leveled against him touches on the wider issue of appropriation of voice. Speaking on behalf of others, as Moelyono was to point out, is an expressive outlet for the artist but can disempower the subject. It can, arguably, constitute exploitation when the artist from an urban middleclass background builds a career on representing the underprivileged poor and peasants. Therefore other artists, FX Harsono among them, sought to distance the art work from individual expression and focus on the concept.

The effectiveness of activist art was questioned by Enin Supriyanto in a catalogue essay for an exhibition of FX Harsono in 1994 where he discussed the concepts of Lucy Lippard. He called activist art ‘…. a ‘paper tiger’ in the face of art institutions and the art business…’ and considered ‘… that the ‘street parliament’ is the most effective way to promote awareness of societal problems….’ Yet Supriyanto, himself once an activist, ultimately agreed with Lippard, writing:

“The strength of this kind of art lies in its ability to convey to another person that they too, in the midst of all the limitations, can do something about what they are witnessing.”[10]Supriyanto, discussing Lippard in Supriyanto, E., 1994, “Listening Once More to Lost Voices”, catalogue essay for FX Harsono’s exhibition at Gedung Pamer Seni Rupa Depdikbud (The … Continue reading

Wright has argued that art can provide an avenue of sociological research and an analysis of attitudes of the time because political avenues for expressing dissent under the Suharto regime were so limited. She writes,

“Hence the arts become a vital area of documentation not only for art history and cultural studies but also from the perspectives of history, politics and social change.”[11]Wright, Astri, 1999, op.cit., p.50

Resistance to Suharto’s government had been consistently and even famously expressed through cultural activities such as literature, theatre and music, but anthologies of essays on contemporary Indonesia prioritize political and economic conditions and separate the arts.[12]Note, for example, the anthology, Budiman Arief, et al. 1999, Reformasi : crisis and change in Indonesia. The three main sections cover the economic crisis, the political crisis and ‘other … Continue reading This can devalue artworks to mere illustrations of events and deny an aesthetic dimension altogether. But recent writing has argued that the relationship between political content and the aesthetic experience is more complex, that it reaches the viewer at a subliminal, emotional level so that the viewer is moved and engaged more effectively by the artist’s intention. Ross Gibson, referencing the arguments of Nicholas Bourriaud, wrote in the catalogue of APT/5,

“This is why art continues to be so important in everyday life. It can give you more than a thesis, more than a polemical message. It can put you through directly felt changes.”[13]Ross Gibson, “Aesthetic Politics” in Queensland Art Gallery and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, 2006, The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art 2006, Brisbane, QLD., Queensland … Continue reading

Activist art in the 1980s – 1990s

Student protest of the 1970s had been effectively quashed and politics banned from campus life under the NKK program or ‘the normalization of campus life’; but certain activist artists continued to pursue socio/political issues and ran the risk of retaliation by the repressive regime. As has already been discussed, modern, decorative and abstract art was taught in art schools and, when permission was sought to exhibit, politically neutral art was favored by those with the power of authorization. Although considered less dangerous than writing, socio/political art had been censored, exhibitions closed, artists threatened and known politically activist artists, such as Djoko Pekik, marginalized.

Censorship by the regime had been inconsistent and criticism in a cultural context was tolerated so long as it did not attract the attention of the general public:

“The critical point in the progression from culture to politics seems to be the public perception of the political implications of the artist’s work. Over the last decade, (the 1980s) there has been a pattern of publication of books or the staging of plays which at first attracted little attention, but as the public response grows, so does official interest, and the books may be banned or the play closed down.”[14]Ross Gibson, “Aesthetic Politics” in Queensland Art Gallery and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, 2006, The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art 2006, Brisbane, QLD., Queensland … Continue reading

In comparison to the other arts such as literature, the visual arts did not attract as much notice for, as Jim Supangkat and others speculated, they were more isolated from, and less understood by, the general public. Agung Kuniawan reminisced in 2005 about the expression of protest under the Suhato regime:

“In those times everyone knew it was impossible to express criticism and protest. I realized that I chose to communicate in the scope of my own peers. Through visual arts and galleries, we could express it all. The scope was limited, but we spoke the same ‘language’, we understood each other. We didn’t talk to the masses.”[15]Virginia Matheson Hooker and Howard Dick, 1993, Culture and society in new order Indonesia, Kuala Lumpur, New York, Oxford University Press, p.5

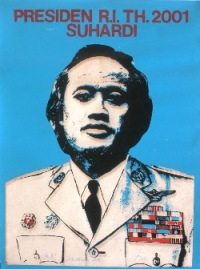

Yet artists could be imprisioned. Hardi, one of the more overtly political artists, was jailed in 1979 for a work he exhibited with the third GSRB exhibition at TIM in Jakarta. The work was titled Presiden 2001, Presidential Candidate, 2001, a date which, in 1979, must have seemed so far in the future as to be a fantasy. Hardi, using a number of images like campaign posters across the canvas, replaced the head of the figure in a presidential costume with his own head – a representation that may have been read as a presentiment of democratic change when ordinary people would claim power. Hardi was ridiculing the futility of elections under the Suharto regime but to the authorities the political succession after Suharto was considered a particularly sensitive subject and the reaction was to quash all such references. Hardi wrote that

“… there was still fear of recriminations if artists expressed their attitudes to social problems through their work…”[16]Quoted by Enin Supriyanto in “Reformation, Changes and Transition, Indonesian contemporary visual arts 1996 – 2006”, in Bollanee, Marc and Supriyanto, Enin, 2007, Indonesian Contemporary Art … Continue reading

Oblique criticism was expressed by ex Communist artists like Djoko Pekik or the Yogyakartan surrealists such as Ivan Sagito and Agus Kamal by their depiction of the lives of peasants and urban poor. Mystery and tension in the work of the so-called surrealists implied that the physical condition of the underprivileged, often poor, older women in the case of Sagito, was also an alienated, psychological state. Dede Eri Supria depicted urban life under Suharto’s modernisation as harsh and dehumanizing, using a cool, detached, photo-realist style that suggested that disturbing or not, these conditions were a fact.

Semsar Siahaan was perhaps the most overt of activist artists to emerge in the 1980s. His style was graphic, figurative and often a confrontational rallying cry against discrimination and repression that the authorities would find hard to dismiss. His activities attracted attention from the beginning of his career when he was expelled from ITB in 1981 for burning a work by his teacher, Sunaryo.[17]The details of this action by Semsar’s are covered more fully by Brita Miklouho-Maklai, in, Exposing Society’s Wounds: Some Aspects of Contemporary Indonesian Art since 1966, Adelaide, The … Continue reading Throughout the 1980s he had difficulty gaining permission to exhibit and when he did so in 1988, the exhibition was turned into a protest movement for ‘liberation’. In Yogyakarta it was closed by the police on the grounds that he was ‘staging the exhibition to humiliate the authorities’.[18]Purnomo, S., 1995, ibid, p88 footnote

His art education had included international experience and drew on international references. One famous painting, Olympia with Mother and Child of 1987, reworked Manet’s famous reclining nude titled, Olympia, into an indictment of the Suharto regime’s policies of modernization. Semsar’s Olympia is a modern harlot being courted by officials with a dog (often understood as a reference to the military) growling at rallying labourers while a starving mother and family wait outside.

That year Semsar joined a Pro-Democracy Action formed in response to the censoring of four publications, including Tempo magazine, and known as the ‘Gambir incident’. Semsar was targeted by the military, beaten and, with a badly broken leg, tortured while hospitalized, which resulted in a permanent disability.[19]A. Junaidi, “Semsar, the rebellious artist”, The Jakarta Post, February 24, 2005, and Wahyoe Boediwaedhana, ” Semsar’s dream stays alive, despite his death”, The Jakarta … Continue reading Semsar then spent the next three years until Reformasi more or less outside Indonesia, travelling on invitations to conferences and exhibitions.

While there were acts of repression by the authorities there was also a conditioned acceptance by the people that the status quo was for their benefit: that stability, security and prosperity were dependent on acquiescence. Ariel Heryanto argued that the New Order regime suffered from serious anxiety about criticism from intellectuals, yet there was also a tendency

“… to give more credence to the repressiveness of the regime than is warranted. This effect of power in turn adds to the efficacy of that power.”[20]Heryanto, A., 1993 Discourse and State-Terrorism a case study of political trials in new order Indonesia 1989-1990, Anthropology, Melbourne, Monash University, PhD thesis, unpublished, p.3

The actual ability of the regime to suppress protest may have been overestimated, but a culture of fear operated to produce complicity in censorship of others and self-censorship in the visual arts.

The public images of conditioned consent were contradicted by subversive expressions of frustrated dissent. The gapura, or the entrance way to a kampung or village was usually decorated with images that reflected the ideology of the regime: images of ethnic unity, two-child families and so on, while the street posters, banners, T-shirts and graffiti were outlets for anger and frustration at the conditions imposed on the people by the authoritarian regime. [21]Laine Berman, “The Art of Street Politics”, in O’Neill, Hugh and Lindsey, Timothy,1999, AWAS! : recent art from Indonesia, Melbourne, Indonesian Arts Society, pp.75-77

Discontent continued to grow, both at grassroots level and among the youth of the educated middle classes as issues of nepotism, corruption and collusion were reported widely in the media and became established in popular perception.

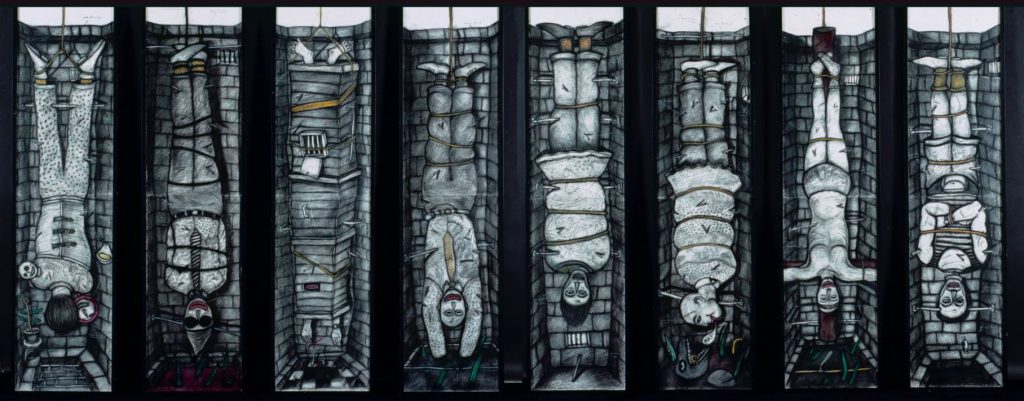

A new generation of artists in the 1990s used art to express socio/political criticism in an oblique, subversive and often bitter way. The work of Agung Kuniawan and Hanura Hosea falls into this category, images of figures in strange costumes or being tortured, the references obscure but disturbing and describing a world where such scenes are accepted as commonplace. Agung Kuniawan won a prize in the ASEAN Art Award in 1996 with a series of charcoal drawings titled, Korban yang Bergembira, or Happy Victims, depicting ten upside down and tortured bodies with the smiling, tragicomedy mouths of clowns.

Agung said,

“I wanted to show how people can live in the midst of a violence and repression so pervasive and enduring that they have become unaware.”[22]Tom Plummer, “Agung Kurniawan: ‘My main theme is violence’”, Inside Indonesia 50: Apr-Jun 1997

He developed a vocabulary of horrors that emanated from what he called automatic drawings without control or logic. They are, nevertheless, carefully drawn, convincingly disturbing and possibly cathartic in intention, an outlet for his revulsion.

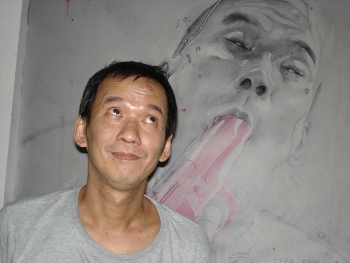

The early work of Agus Suwage, although similar with dark and disturbing elements, took a different direction. Suwage favored drawing as a medium, like Agung Kuniawan, but the central figure is often himself as the vehicle through which the fears and disturbances of an unnatural environment are played out. The central theme of his work became the relationship between the madness of the world – beginning with the oppressive regime in the 1990s but then extending to all aspects of contemporary life – and its effect on his own mental and physical state. Nothing is sacred: the explorations are sometimes cynical, sometimes hedonistic and they often have a maniacal edge, suggesting that beneath pleasure there is only nihilism.

Suwage graduated from ITB in 1986 in Graphic Design and his career as an artist did not develop until nearly ten years later. One of his first exhibitions was This room of mine, held at Lontar Gallery in 1997 and accompanied by a limited edition artist’s book of images that date from 1995. His ‘room’ reflects conditions under the Suharto regime with disturbing figures placed in a strange space. In one image titled, Once upon a time in a prosperous and peaceful place, the emblem of Indonesia is on the back wall with earth piled up before it, a schoolboy is suspended on a side wall and a man covering his face with his hands is in the foreground. Although the meaning may be unclear, the sense of dislocation and tension is strong. Suwage stated in the book:

“For me, the creative process is therapy, capable of healing the disturbed mind, a release from the nagging questions of daily life as well as socio-cultural realities, restrictive norms, socio-political imbalances, the economy, trust, knowledge and religion that cause so much human tragedy.”[23]Agus Suwage, c. 1996, This room of mine, The Lontar Foundation, Jakarta

By the late 1990s two artists in particular had developed a politically activist art practice, Moelyono and FX Harsono, yet neither of these artists was taken up to a great degree by the international art circuit. Moelyono continued to work with village communities in activities that have not translated easily to the gallery exhibition system and FX Harsono had to support himself with a graphic design studio. Recognition came later for Harsono, culminating in a prestigious retrospective exhibition at the Singapore Art Museum in 2010. The relationship between local activist art and international success is complex and a study of these artists and their careers indicates why some art works are more compatible with international exhibition than others.

Two political artists of the 1990s

Moelyono

The focus of Moelyono’s work in rural life highlights the distinct divide between the interests of the urban population and those of the rural areas who still constitute 60% of the population.[24]Urbanization stood at 41% in the census taken in 2000, note figures quoted from Badan Pusat Statistik, http://www.library.uu.nl/wesp/populstat/Asia/indonesg.htm accessed 19/10/06 His work in Central and Eastern Java gives a particular insight into the repressed and exploited conditions of rural villages but whose life is rarely represented in international exhibition. He exhibits in art galleries and has developed international contacts but his oeuvre sits uncomfortably both with Indonesian artistic conventions and those of the international biennales.

Moelyono was at odds with the art establishment from his student days and was committed to using art to assist marginalized and underprivileged people. He rejects stereotypical depictions of emaciated farmers or downtrodden workers, saying that this form of contemporary art ‘only objectifies the poor.'[25]Tom Plummer, quoting Moelyono in, “Art for a better world”, Inside Indonesia No 53, January – March, 1998, p.26 Such work, he says, presents the underprivileged to the educated elite without empowering them and it perpetuates the traditional Javanese hierarchy that has one group speaking on behalf of another.[26]Moelyono interview, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta Such art is an expressive outlet for the artist alone and “the problem of poverty ends up in a collector’s gallery. Silenced! Mute!”[27]Moelyono, “Seni Rupa Kagunan: a Process”, in Schiller, J. W. and Martin-Schiller, B., 1997, Imagining Indonesia : cultural politics and political culture, Athens, Ohio, Ohio University … Continue reading Moelyono considers that although Sudjojono, Hendra Gunawan and Affandi were sympathetic to the plight of the poor, in the end their art became just an art market commodity because they adhered to the concept of fine art as the refined work of gifted individuals and distinct from the supposedly unrefined techniques of the people. According to Moelyono, Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru smashed the aesthetic hegemony of the ‘fine arts’ and ‘democratized’ art by incorporating contemporary experience, but only displayed popular idioms and icons, not the art of the people themselves who were still treated as ‘mute and passive’.

Moelyono considers that Kagunan, or fine art, should encompass artists such as

“… trance dancers, tayub dancers, painters and illustrators, keris makers and many others. The world of art does not know class distinction, only distinctions in the level of quality.”

True democratization was to recognize all the work of the people as art.[28]Schiller, 1997 ibid., pp.122 – 126. Tayub is a form of dance where men are invited to dance with a professional female dancer. A Kris is a wavy-edged knife, sometimes considered sacred

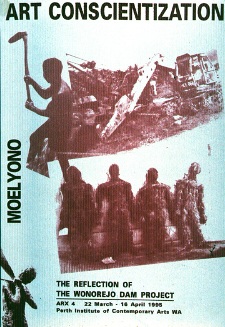

Moelyono shared a similar approach to art with the German conceptual artist, Joseph Beuys, in considering everyone is an artist and everyone can make art. He has been called a conceptual artist as he values the practice and discussion of art over the form it takes, and he uses the terms ‘praxis’ and ‘dialogue’ frequently.[29]R. Fadjri, “Moelyono’s art invites dialog on social issues”, The Jakarta Post, Sunday May (date unknown) 1997, p.14 Like many, Moelyono resisted his art education at ASRI. He reported “When you painted with textured moss green, dark browns, somber colors and decoratively, you got an A, while if you painted in a ‘Pop’ style, you would only get C, or at best a B.” The teachers, artists “…Pak Widayat and Pak Fadjar Sidik, were textbook representatives for the ideology of ‘high art”.[30]Hasan, A., 1998 “Moelyono dan Seni Rupa Penyadaran”, Galeri Lontar, Jakarta. An interview between Asikin Hasan, curator at Lontar Gallery, with Moelyono for his exhibition, translated by … Continue reading His final submission for assessment was an installation representing the poverty of farmers from Waung, a swampy area near Tulungagung where Moelyono was born and still lives. He laid out pandanus mats with banana leaf containers which held the limited produce from the farmers’ waterlogged fields and he intended that this would provoke a dialogue with the people on campus concerning conditions in rural areas. Titled KUD, Kesenian Unit Desa, or Village Unit Art, it was rejected by the jury on the grounds it did “…not fulfill the requirement of an art work in the ‘Art of Painting Department.'”[31]Biografi in Moelyono, 1995 Art Conscientization, The Reflection of the Wonorojo Dam Project, ARX 4 22 March – 16 April, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts WA It was, in fact, a conceptual work of art that challenged the concept of art itself.

Moelyono worked with FX Harsono in Jakarta in graphic design but free-lanced, working with NGOs making posters and booklets concerning the victims of Suharto’s modernization and issues such as the degradation of the environment. He has been greatly influenced by Brazilian educator/philosopher, Paulo Freire, and frequently uses Freire’s term, Conscientization, from the Portuguese word for ‘consciousness’, interpreted to mean ‘consciousness-raising’. Freire proposed in his Pedagogy of the Oppressed that education should heighten awareness of the contradictions in social, political and economic situations and empower people to recognize the causes of their oppression and to take control of their lives.[32]Freire’s work was published in Indonesian as Pendidikan sebagai praktek pembebasan, or Education, as a practice of freedom, see Paulo Freire, 1984, Pendidikan sebagai praktek pembebasan, … Continue reading

According to Moelyono,

“The role of an arts worker is to assist in the regrowth of a popular artistic aesthetic by aiding in the creation of art forms of high quality rooted in the traditional culture, the environment, and everyday lifestyles. This also should not be seen merely as “social work”.”[33]Schiller, 1997 op.cit., p130

Brumbun

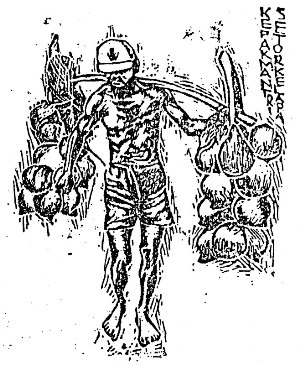

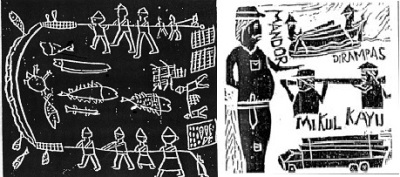

One of Moelyono’s early experiences illustrates not only his techniques but the repressive environment in rural communities under the Suharto regime. In 1986 he began his ‘praxis of fine art’ at Brumbun and the nearby village of Ngerangan, 26 km from Tulungagung on the southern coast of Java. Brumbun was a village of some 100 people in approximately 34 households, who had been allowed to settle there in 1963 by the district authorities and the forestry service. They had been either landless in their original villages or failed transmigran, inhabitants of overpopulated areas who had been resettled in less populated areas.[34]See Vickers, A., 2005 op.cit., pp. 193 – 194. Vickers describes the variety of experiences incurred under the transmigrasi program. Few transmigran prospered The district authorities allowed them to remain on the basis that they could not own the land they occupied and they must cultivate coconuts and pay a tax of rice and coconuts to Pak Mandur, the government official in control. They were extremely poor fishermen and farmers in an isolated, mosquito-ridden village, which could only be reached by a walk through the forest from the point where public transport ended.

Moelyono offered to become the art teacher at the very basic school they had in the village. His position was understood as that of a teacher rather than artist, as the concept of artist was unfamiliar to the villagers. The parents were concerned that his play activities took children from economically essential work, but when an exhibition was held in Tulungagung and some of the works sold, the proceeds and donations provided books, school clothes and water containers for the village, and the parents became supportive of his project.[35]Haryono, Endy and David, 1990 “Moelyono: art and social transformation”, Inside Indonesia, No. 25, Dec. 1990, pp.29-30

Moelyono began by introducing children to drawing. “I tell the children that drawing is easy and they can make a drawing by playing, drawing a line in the sand. They make a long line in the sand and if they like, they make a drawing. With the drawing we discuss what problems they have.”[36]Interview, Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta From lines in the sand Moelyono then introduced drawing on available paper which led to drawing simple shapes, then to objects observed by the children and significant events that affected their lives. It was when the children made drawings of the burden their parents faced in delivering the tax to Pak Mandur on Sunday, carrying the coconuts to his house five to ten kilometres away, that the drawings gained another dimension. Pak Mandur saw the children’s drawings when they were displayed on a bamboo wall in the village and became very angry.

The police interrogated the Kepala Desa, or village headman, but he

“… is very easy talking. He said, why are you angry? These drawings are only by children and they are very funny”.[37]Interview, Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta

Moelyono mounted an exhibition of the village drawings and between 1987 and 1989 it travelled to Tulungagung, Surabaya, Yogyakarta, Salatiga, Solo and eventually Jakarta. When Moelyono attempted a similar program with adults, it was stopped by the local district authority on the grounds that it was political.[38]Schiller, 1997 op.cit., p.134 The officials, police and military visited the village and Moelyono was taken and interrogated, accused of being komunis, or communist, and although there was no violence, the ‘interrogation was not good’. They demanded that he obtain five different permits to continue his work which eventually he was able to do with the assistance of a contact in the government bureaucracy. The exhibitions did, though, provoke the dialogue he sought. There was a discussion with the villagers concerning their problems, then with artists, student activists and social scientists, and financial support was provided by an NGO.

It was when he took the catalogue from the Jakarta exhibition to the Bupati, or regent of Tulungagung, that life began to change. The Bupati visited the villages and ordered that a road be constructed with government funds, and the road ended their isolation allowing them to sell their produce directly to the market. The administration provided some facilities: there was a

“… program for school building, a program for cementing the floors, tiles replaced thatched roofs, the musholla, (a room or space for the daily prayers) was repaired, and the fishermen obtained fibreglass boats on credit and a diesel generator for electricity in the houses. Several village people opened stalls, bought motorcycles and one person boasted a satellite dish.”[39]Hasan, A., 1998 op.cit., p.9. Recognition by the bureaucracy allowed a village to receive government funding for building facilities from such programs as INPRES, the Instruksi Presiden program

Access to the outside world was, though, a two-edged sword and Moelyono has had to acknowledge a downside to such projects. The Indonesian government declared 1991 the Visit Indonesia Year, and as part of this promotion the local government proposed that Brumbun bay become a tourist area. The plan was to build a parking area, a traditional restaurant, a crocodile farm and tennis courts, while at Ngerangan a swimming pool was to be built on the sawah, or wet rice fields, a footnote to the proposal bluntly noting: ‘local fishing village to be relocated’.[40]Schiller, 1997 op.cit., p. 135 The people were being moved off the land by progress, development and tourism, the cornerstone policies of Suharto’s regime. A drawing by one child showed the upheaval in his family after their rice field was converted into the public swimming pool.[41]R. Fadjri, “Moelyono’s art invites dialog on social issues’, The Jakarta Post, Sunday May (?) 1997

In 1990 Moelyono was reported as saying,

“The problem for the villagers is how to become involved in these projects to their benefit. I don’t know what will happen. The administration has forbidden any further formal meetings of the villagers to discuss their problems, as it is not permitted to discuss social problems at village level under existing law since 1974.”[42]Haryono, Endy and David, 1990 op.cit.

Moelyono left the village and began work on the Wonorejo dam project in 1995. In 2001 he said

“… many people went to Brumbun because it is a very nice place… local tourists. It’s a good life, they have cars, motorcycles, television… no telephone, that is too difficult.”[43]Interview, Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta

If one measures the loss of sawah against the gain of these material benefits, it is clear some villagers won and some lost in Suharto’s process of modernization.

Marsinah

The death of Marsinah, a labour activist in a Surabaya watch factory, became one of the most public scandals of the Suharto regime. Marsinah had been in the forefront of protests at the watch factory, PT Catur Putra Surya, where she worked, demanding the government-approved minimum wage be paid to the employees. In May 1993 some of the protesters were taken into custody by the military and although Marsinah was not one of them, after she visited the military offices enquiring after her friends, she disappeared. Three days later her body was found in a hut next to a rice field 200 km from the factory. She had been tortured and raped and suspicion fell on the military that had been supporting and enforcing the factory owners’ policies. There was a ground swell of protest until by July every newspaper in Java had carried the story.[44]Benjamin Waters, “The Marsinah Murder”, http://www.asia-pacificaction. org/southeastasia/indonesia/publications/doss1/marsinah.htm accessed 13/10/06; also version printed in Inside … Continue reading

Moelyono, in conjunction with Marsinah’s co-workers, organized an exhibition at Dewan Kesenian Surabaya, the Surabaya Arts Centre, on the Javanese 100th day of commemoration after her death. The exhibition, Pameran Seni Rupa Untuk Marsinah, Art Exhibition for Marsinah, was an account of the last days of Marsinah’s life and made references to her background and that of a whole generation of Indonesian workers who had come from farm to factory. Following his usual procedure and in a process of healing, Moelyono worked with Marsinah’s friends and co-workers, making woodcuts and an installation.The work included life- sized figures of straw, a portrait bust of Marsinah and cement plaques with the Javanese word ‘inggih’, on them which means ‘yes’ to someone in a higher position. By associating this traditional gesture of submission to authority with an exhibition of protest about that authority, they were

“… deliberately breaching the bounds of traditional Indonesian protocol, as well as more contemporary restraints”[45]Ewington, J., 1994 “The exhibition that never opened”, Art and AsiaPacific (Australia) 1 (4): 34

Three hours before the exhibition was to open on August 12th, 1993, the police ordered that the exhibition be cancelled. The police lieutenant colonel, Ahmad Rifai, was reported as saying in justification of its closure that,

“It was not an ordinary exhibition. Clearly there was an attempt to politicize the Marsinah case through the exhibition.”

When guests arrived to closed doors, an impromptu discussion or komentar[46]It is understood that the spontaneous komentar often acts as safety valve for the expression of opinions suppressed by manners or authority, while the diskusi is a more organized discussion often … Continue reading occurred that became part of the nation- wide protest, and although no photographs were permitted officially, some do exist of the exhibition. Marsinah’s name has remained symbolic and the case provoked strong responses from the arts community, but as Moelyono has said,

“the International Labour Organization, (ILO) which was influential, put pressure on the Indonesian government, but we still don’t know who killed Marsinah.”[47]Interview Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta

Moelyono formed the Yayasan Seni Rupa Komunitas, or the Community Art Foundation, in 1993 and continued with his rural-based projects. The next project was at Wonorejo village, East Java, and was associated with the building of a dam that displaced hundreds of families, many without fair compensation. Moelyono sought to reconnect the villagers and reinvigorate their culture by assisting a group in performing their traditional Jaranan, or horse dance, which had previously been banned for its association with Communist party activities. It involved giant horses made from cow leather and a series of dances culminating in one performed in a trance-induced state. The performance was cathartic, a release for tensions, but also a platform for discussion, for each rehearsal and performance was an opportunity for the villagers to discuss the issues affecting them. Moelyono credits their ability to negotiate a better price for the land to this increased awareness and confidence to articulate their issues.[48]Interview Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta

The bridge between rural society and art

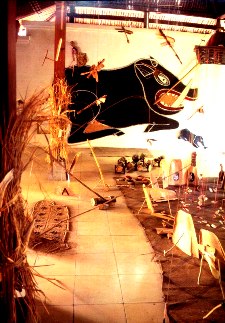

Through his own work, Moelyono attempts to bring the rural experience to the art gallery. The concept of the Wonorejo project was reconstructed in his exhibition, Seni Rupa Refleksi Lingkungan or Art Reflecting the Environment, at the Taman Budaya Surakarta Gallery, Central Java, in 1994. In 1995 he took this project to ARX 4 (Artists Regional Exchange), in Perth, Western Australia, and was supported for an intensive residency and exhibition at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts by the Sam Bung Foundation and the Australia Council.[49]ARX 1995, Torque, Perth, Western Australia, Australia & Regions Artists’ Exchange. The Indonesian artists were: Moelyono, Arahmaiani and Agoes Hari Rahardjo (Agoes Jolly). The first ARX was … Continue reading The booklet, Art Conscientization, The Reflection of the Wonorejo Dam Project, was produced for the exhibition and Moelyono organised a performance titled Yang Diikat, Those who are Bound, outside the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, or PICA. As one participant described it:

“… the performance involved a (modest) gathering of people, myself included, who were required to bind with yellow tape (the colour of the state party, Golkar) the performers… as peasants, villagers and farmers dance slowly and play traditional percussion.”[50]A full description is given in Hillyer, Vivienne, 1997 Moelyono / Praxis, unpublished submission for B. Arts (Visual Arts), Edith Cowan University W.A. p.8

Moelyono’s performance and installation art does not sell and, unlike some other Indonesian artists, he produces little in other media that is more easily marketable. He supports himself through the foundation with art-related projects for NGOs and organizations such as UNICEF. He has gained considerable recognition and respect but the transition of his art concepts from village to local or

international exhibition has had its difficulties, exhibition organizers finding his work awkward to manage and reviewers difficult to comprehend. A review of his Yogyakarta exhibition in 1997, stated,

“Although Moelyono may be considered in step with contemporary art trends, the emotionally complex and testing nature of his work is no doubt too disturbing for many members of the Indonesian public.”

Another (unidentified) review said,

“Even if Moelyono has been frequently invited to international workshops, such as in Australia and in Japan, one needs to be more appealing in the market here”.[51]The exhibition was Tumpengan Kelapa, Ceremonial Coconuts at Galeri Bentang Budaya, Yogyakarta. The word for coconut, kelapa, is similar to the word for head, kepala, an association reinforced by the … Continue reading

Moelyono has been invited to submit work for international exhibitions in Japan, in 1996, the Gwangju Biennale in 2000, India in 2004 and a workshop in Malaysia in 2005. In APT/3, 1999, his work was titled Animal Sacrifice of the Orde Batu (Stone Order), 1965 – 1999. The dates refer both to the violence of 1965 and the riots of 1998 with the disturbing attacks on Chinese Indonesians, and the pun is a play on Suharto’s Orde Baru, the New Order regime. The work involved an up- turned car with red-painted steps holding offerings leading up to it. Graffiti was written on the car and banners saying Cina (Chinese) and Pribumi, (indigenous native) on it. The installation is incomplete for, according to the description in the catalogue essay, headless statues were to surround the car. They were intended to represent famous temple statues damaged by souvenir hunters while also referring to the violence of 1965 when headless bodies floated in the rivers,[52]Adi Wicaksono, “Moelyono”, in Queensland Art Gallery, 1999 Beyond the future : the third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, South Brisbane, Qld., Australia, Queensland Art … Continue reading but clearly it was easier for the gallery staff in Queensland to obtain a burnt out car than headless statues. Caroline Turner stated that “The original concept for the work (was) unable to be realized at the time”,[53]Turner, C. ed., 2005 op.cit., p.208 but the references were confusing and his concepts were not translating well into an international survey exhibition format.

Moelyono himself says he does not find the transition from village to gallery difficult – his real work, he says, is in the village, that is his praxis or action, and the work in gallery is for reflection, the consciousness-raising activities being more important to him than personal expression.[54]Moelyono, interview, Tulungagung, 10/05/05

SBAT

Most recently Moelyono has been exploring issues affecting communities near Ponorogo including the effects of pesticide use in local farming and early childhood education. He has developed a learning program for preschool children which he calls Sanggar Bermain Anak Tani, SBAT, the Farmers’ Children Play Group, for villagers who cannot afford either the time or cost of sending their children to school. Cemeti exhibited his installation as part of Exploring Vacuum in 2003.

Ultimately his activities in the village were affected by rising Islamic fundamentalism and Western anxiety concerning it. The support he received from the British NGO, Foster Parent Plan, was withdrawn because, according to Moelyono, ‘they were a Christian organization and the villagers were Muslim’. At the same time there was pressure from the pesantren, or Islamic religious school below the village, to withdraw children from Moelyono’s play group because his activities were not related to prayer rituals or Muslim activities. Typically, the culture of the farmers included animist traditions but Moelyono said, (the pesantren) ‘..didn’t like the villagers praying to the gods of the padi‘. Although unpaid, Moelyono has continued to provide training for the village mothers in preschool education, an activity that elsewhere would be provided by the government.

The question arises as to whether Moelyono’s work should be evaluated as art or social work and whether the two activities are mutually exclusive. A brief survey of his career and the organizations he has worked for, among them: OXFAM, Save the Children Fund, Plan International, World Vision International and INSIST, the Institute for Social Transformation, indicates they employ him as a social worker. But for Moelyono, the two aspects are closely connected: he is a practicing artist and art for him must have a social purpose. He has been often quoted as saying that the role should not be seen as social work alone:

“The role of an arts worker is to assist in the regrowth of a popular artistic aesthetic by aiding in the creation of art forms of high quality rooted in the traditional culture, the environment, and everyday lifestyles. This also should not be seen merely as “social work”.”[55]Schiller, 1997 ibid, p.130. Also in Marcel Thee, “Evoking Memories of 1965 in Indonesia”, September 12, 2009, The Jakarta Globe. Hendro Wiyanto, who curated Moelyono’s exhibition in Jakarta in … Continue reading

By what criteria, then, is his work to be evaluated? Were the rural communities empowered through art activities? Do his exhibitions in art galleries raise awareness of rural conditions, effecting change in attitudes and promoting active assistance? Recalling the concepts of Ross Gibson/Nicholas Bourriaud, does his art extend beyond the polemical to direct engagement with feelings? It is a noble cause but a large ask for a work of art. The strength of his art lies in Moelyono himself: like Joseph Beuys the art has become the artist and his actions. The artwork is no longer an object but a concept that is transferred through the performance and actions of the artist and it is the artist who is engaging and convincing the audience. But regrettably, his influence and impact is primarily within Indonesia as an activist artist, not internationally as a conceptual artist.

F X Harsono

Moelyono and Harsono share similar attitudes to social activism but the issues are different ones for Harsono. “Moelyono uses very effective strategies in the community, but I am not Moelyono…I can’t work like him as I don’t have his community”.[56]Interview FX Harsono, Jakarta, 26/06/01 Like Moelyono, Harsono is committed to ‘art that has meaning and connects people’, but is also interested in the theoretical and conceptual basis of artwork and has published essays at home and abroad.[57]Harsono’s CV lists a number of published essays and articles in Kompas, Tempo and Forum as well as being overseas editor for Artlink, an Australian quarterly magazine, 1993/4. He helped to … Continue reading He was concerned that, following Reformasi, art was being used only as an illustration for social and political issues. He said,

“Yes, art is a medium for advocacy but some artists only try to find what the popular issue is at the moment to put in their art.”

Harsono was born in Blitar, South East Java, in 1949, just as the Republic of Indonesia was being born out of the wars of independence from the Dutch, and the development of his career parallels the development of the new republic. His family was Tionghoa Peranakan, or of mixed Chinese Indonesian descent, as distinct from Totok, the Chinese who have arrived more recently and speak a Chinese language at home. Chinese Indonesians are generally seen in Indonesia as a homogenous migrant group and distinct from indigenous Pribumi, but not only is this historically incorrect, there is considerable diversity in where people came from and where they settled, and ethnic identity changes from generation to generation. Since Independence for example, parents that spoke Dutch at home have children who only speak bahasa Indonesia.

Harsono’s birth name was Oh Hong Boen, but as his mother was a devout Catholic, he was baptised Fransiskus Xaverius. FX are fortuitous initials for an artist and Harsono is aware of the pun.[58]Harsono’s prefix initials are variously recorded as F.X. or FX, he himself using the latter in communications Under the Suharto regime Chinese identity and culture was systematically suppressed, Chinese schools were closed and Chinese languages, script and festivals were banned. The only Chinese words Harsono can now remember and write are those of his Chinese birth name. A presidential directive in 1967 required ethnic Chinese to adopt Indonesian names and, at the age of 18, he chose the name, Harsono, simply because it meant ‘happy man’, he said.[59]Harsono speaking at Gallery 4A, Sydney, 18/02/12. The Presidential Decision 240 of 1967 mandated the assimilation of foreigners and supported a previous directive of 1966 for Indonesian Chinese to … Continue reading His identity card, as for all Indonesians, indicates both religion and ethnicity which provides an opportunity for extortion or persecution. The KTP, Kartu Tanda Penduduk/ Pengenal or resident identity card, defined Indonesian Chinese as ‘WNI’, Warga Negara Indonesia or ‘citizen of Indonesia’ rather than simply ‘Indonesian’, as would be the case for ‘Pribumi Indonesians’. WNI was, therefore, a euphemism for an ethnic Chinese and outsider, and during the riots in 1998, gangs used ID cards to identify and persecute Chinese Indonesians.[60]The Yogyakartan artist, Samuel Indratma, interviewed 11/07/01, confirmed the concern caused by having ethnicity and religion recorded on the compulsory identity card. After the attacks on the Chinese … Continue reading

The targeting of ethnic Chinese for discrimination and violence has reached horrific levels at two particular periods during Harsono’s lifetime, both during major changes in national power as, during times of political upheaval, it has been useful to deflect dissatisfaction onto minority groups.[61]Note discussion in Chapter 2: Jemma Purdey, 2006, Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia, 1996-1999, Asian Studies Association of Australia and Singapore University Press, pp. 23-30 The first period in 1965 marked the rise of General Suharto and the second, his downfall some thirty years later in 1998. In 1965 Harsono was 16 years old and in his first year of senior high school in Blitar when Chinese Indonesian youths were required to prove their loyalty to the nation by assisting the military to restore order. He was fortunate his father advised him to avoid involvement for, in the confusion, mayhem turned murderous and loyalties became confused. Were you Chinese first or Indonesian? Were you a victim or a persecutor?[62]Hendro Wiyanto, 2010, “A Brief Biography from Tjoe Tien Alley” in Re: Petition/Position/FX Harsono, Langgeng Art Foundation, Magelang, Central Java, pp.123-135 Under the Orde Baru, all references to these events were altered or suppressed so that young Indonesians today are not aware of their own history, even when their families may have been directly affected. The silencing of the oppressed was to become a major theme of Harsono’s work.

Harsono’s career was dedicated to what he called the ‘social and political’ and the body of his work had been a response to the issues and events in Indonesian history he has lived through. Not only his sense of ethnic marginalization, but his frustration at the repressive Suharto regime, drove his art making and, like many activist artists, he has used art to raise awareness and to reach an audience beyond the art gallery in the hope of effecting change. He rejected traditional Javanese art as a means identity that was so important to the early supporters of independence, and eventually he also rejected the modern urban identity promoted by Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru. He said:

“If we are to find our identity we must transform people’s problems, the people who are connected to the culture………. We cannot just put the traditional images into painting to say this is the Indonesian identity. A lot of people were repressed by the New Order so that is why I make social and political art.”[63]Harsono, interview, 26/06/01

In 1969 Harsono entered the Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia, ASRI, (now ISI), and his early student art work was geometric in style, but at a time of growing student activism, he considered it sterile and felt his art should reflect a greater social awareness.[64]Hendro Wiyanto, 2010, “From an Imaginary plane to Social Dynamics (1972-1974)” in Re: Petition/Position/FX Harsono, ibid, p. 62 In 1972 he formed the Kelompok Lima, or Group 5 with four other art students interested in experimental art and it was to be one of a number of activist groups he joined throughout his career.[65]The artists with Harsono in Kelompok Lima were B. Munny Ardhi, Siti Adiati, Nanik Mirna and Hardi In December 1974 he was one of fourteen young artists to protest the bias towards established, decorative painters in the selection for the Jakarta Biennial Grand Indonesian Painting Exhibition, which became known as the Desember Hitam or Black December protest. ASRI expelled the students involved, including Harsono who finally completed his art education later at Institut Kesenian Jakarta, IKJ, in 1991. The members of Desember Hitam joined students from ITB in Bandung the following year to form the basis of Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, the New Art Movement.

One of Harsono’s early works from the GSRB period is Rantai yang Santai, the Relaxed Chain, 1975, that was shown again recently in his retrospective solo exhibition, Testimonies, at the Singapore Art Museum in 2010. The mattress implies something intimate, even the two pillows could represent people, but they are separated and held by chains. The title suggests that even in the privacy of their bedrooms and in times of relaxation, people have been conditioned to accept control. In the new experimental art form of installations he used found or manufactured objects which eliminated the marks or gestures of the artist and distanced the work from the artist’s subjective feelings. The formal or the aesthetic properties of the work are not important, it is the concept, the comment on Indonesian society under the Suharto regime, that is significant.

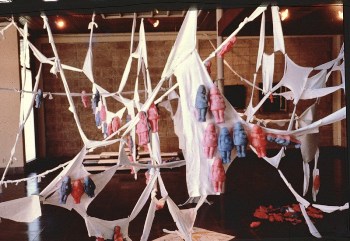

In the work, Transmigrasi, 1979, colourful doll-shaped krupuk, the popular crackers, are trapped in old clothes which have been torn and hung like a web. Krupuk are the food of the poor but the red and blue dyes are poisonous. These dolls represent powerless people caught in a policy of the government that was designed to address overpopulation by transporting the poor from overcrowded areas to outer and less populated areas of the Republic. It was a scheme funded by the World Bank through development aid, and some individuals did prosper. But for the majority it was a miserable upheaval, caught in political power games and dumped amongst resentful locals without materials or assistance, as Moelyono had found at Brumbun.

By the early 1980s the members of the GSRB were pulling in different directions, some towards writing, some focusing on art activism and others developing careers in design and advertising. A heavy crackdown in tertiary institutions had suppressed student activism on campus. Harsono concentrated on working as a graphic designer and eventually established his own commercial graphic design studio, Gugus Graphis, or the Graphic Group in 1984, to support himself and his family.

Art, when he could make it, was in response to issues or events and was not in the form of painting or prints that would sell in the art market. He combined with other former ASRI students in an art collective and they researched environmental issues with the recently formed WAHLI, Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia, or Indonesian Environmental Forum. In 1985 they held an exhibition titled, Proses 85, concerning pollution of the waterways and the exploitation of timber resources. His work titled, Logging, was an installation of recycled black boards with white trees silk screened onto them and propped against the wall or piled on the floor to reflect the fragility of the forest.[66]Note the description of the exhibition in Astri Wright, 1994, Soul, spirit, and mountain: preoccupations of contemporary Indonesian painters, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, pp.215-216 Again, as with the rest of his work, printmaking is not to reproduce an aesthetically pleasing, commercial art print but for an unmistakable message. Combined with their collective way of exhibiting, their use of design and advertising techniques further distanced the artists from making work that was an outlet for their individual expression.

In 1994 Harsono used his art to respond to one of the most famous examples of political censorship. Tempo, Indonesia’s oldest weekly news magazine, published a story that reported a dispute within the government concerning the purchase of second-hand warships from East Germany. Suharto responded by criticizing the press for fanning controversy and ‘jeopardizing national security’. Tempo, along with two other publications, was banned. Goenawan Mohammad, who as editor had, since the 1970s, been carefully navigating government censorship in order to publish, now became “the most dangerous man in Indonesia”. As a supporter of democratic reform, he founded an independent journalists’ association at Komunitas Utan Kayu in Jakarta, and Tempo was not openly published again until after Reformasi in 1998.[67]See Steele, Janet E., 2005, Wars within: the story of Tempo, an independent magazine in Soeharto’s Indonesia, Jakarta; Singapore, Equinox, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p.233

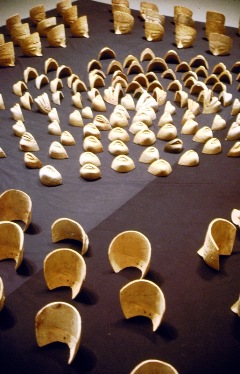

At that time Harsono was in the process of mounting his first solo exhibition titled Suara, or Voice. In direct response to the banning of Tempo, he created, The Voices Controlled by the Powers from one hundred Javanese masks or Panji that he bought from roadside stalls in Malioboro Street, Yogyakarta. Masks in Harsono’s work represent the people, here silenced by the mask being cut in half, which separated the speaking part of the face from the seeing part. Masks are loaded with meaning in any cultural context as they disguise appearance and hide feeling, leaving neutral, bland features. Harsono laid the masks in a square or grid, a format occurring often in his work and which implies the imposition of a rigid system of control. But beneath this façade there is potential violence for, in the centre, some of the masks are baring teeth. There is a strong Javanese sensibility about the work in the way elaborate detail is restrained inside a pattern: a controlled energy which can be seen in Javanese arts from wood carving to Batik.

Silencing of the people became a constant theme in Harsono’s work in the 1990s. In Voice without a Voice/Sign of 1993-4, hands spell out the word, Demokrasi, in a sign language for the deaf, the last hand, ‘I’, the personal pronoun in English, being bound by a cord. The original intention was that the work would be easily portable, to be mounted in the streets like political posters that could be swiftly removed if trouble ensued. The images have been released by a photo-etch, screen-printing technique onto large canvasses, techniques that by the end of the 1990s had been transformed by computer digital imagery.

On a rising tide of demands for reformasi and cynicism concerning the upcoming elections, Cemeti held a group exhibition in 1997 titled, Slot in the Box. As part of the exhibition, Harsono gave a performance on the alun-alun selatatan, the southern square behind the Sultan’s palace, for a select audience of friends and journalists, and the remains of the performance and video documentation became an installation in the gallery.

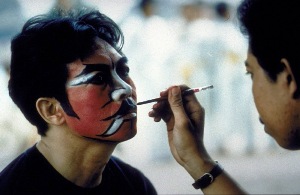

The images from the performance, titled Kurban/Destruksi 1, Victim/Destruction 1, show Harsono wearing a suit, the modern symbol of power dressing, having his face painted as the evil king from the Ramayana. Then, using a flame thrower, he burned masks that had been placed on the seats of chairs and attacked the chairs with a chainsaw. The symbols were easily read in an Indonesian context: the chair was a traditional Javanese symbol of power and, as before, Harsono used the masks to represent the people who were being burned by the authorities until the power of the chair itself is destroyed. The symbolism was transparent, the performance raw and brutal and some feared he would provoke a riot. Dwi Marianto found it unconvincing as Harsono was inept with the chainsaw and it became embedded in a chair;[68]Marianto, D., 1997, “Slot in the Box: opinions and perspectives on the subject of pemilu through art”, Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs, vol. 31, pp.215-216 but the rawness of the performance was in keeping with power politics at election time: the rough and tumble of demonstrations and flag waving.

Reformasi was a particularly tense time for Harsono and his family when being on the streets was dangerous and neighborhood Christian churches were burned. Harsono was deeply shocked by the events and afterwards his art was to take a different, more introspective direction. He said,

“I haven’t made artwork (Gallery pieces) since 1998 because I feel so upset. So I work for a voluntary organization caring for women who were raped or attacked in the riots. I am a Catholic so I pray ‘Our Father who art in heaven…’ and it seems I must forgive, but it is difficult. I can’t forgive the people who did this.”[69]Harsono, interview, 26/06/01

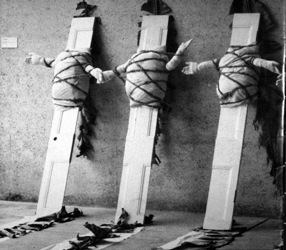

Harsono’s work in the 1990s was attracting the selectors for international exhibitions. He participated in ARX/2 in 1992 and in 1995 he was a consultant and curator for Indonesian artists in ARX/4 which included Moelyono. He was another who reported that ARX gave him opportunities not found in Indonesia. In 1993 he was selected to exhibit in APT/1 and presented an installation, Just the Rights, with sections of doors wrapped with shapes that represent silenced and restrained figures. But it was to be another ten years before Harsono gained truly international recognition, culminating in his retrospective exhibition at the Singapore Art Museum in 2010.

Mella Jaarsma, visiting Harsono with Julie Ewington who was in Indonesia selecting work for APT/3, asked him why he did not make a living from art.

“I said, I never sell art, I can never make art which sells… I could not survive by selling my art, nobody wanted to buy my installations.”[70]Harsono, interview, 26/06/01

Installations if they are sold at all, are more likely to be purchased by institutions, but such purchases are few and far between. Editions of Voice without a Voice/Sign are now in the collections of both the Queensland Art Gallery and the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, but in 2001, The Voices Controlled by the Powers that had been exhibited in the Traditions and Tensions exhibition, had not sold and Harsono reported that it was stored in his studio. Harsono, as a matter of principle, avoided producing painting or sculptural work that could be assessed as a conventional commodity. Art was activism and, added to a long gestation period for his artworks and the commitment to his design business, his work was not prolific.[71]In 2010 Harsono reported that the design studio, Gugus Graphis, had been closed for 2 or 3 years and he was now a full time artist and lecturer at the Universitas Pelita Harapan. Personal … Continue reading The quality of his work is highly regarded and his integrity as an artist greatly respected, but in comparison to other Indonesian artists he was late in gaining the attention of the Western institutions that had provided others with international connections and full time careers.

Three other artists, Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani and Heri Dono were among the first to be selected for international survey exhibitions and, being repeatedly selected, they had, by the end of the 1990s, almost entirely constructed their careers outside Indonesia. Now, some two decades later, they are not the only internationally recognized Indonesian artists but being, the first, their careers can illuminate the pressures internally in Indonesia that encouraged them to exhibit elsewhere and the way in which they met the preferences of the international selectors. Their careers will discussed in Chapter 7: Global Artists.

References

| ↑1 | Caroline Turner interviewed by Jennifer Moran for Pandanus Books, Newsletter, Spring 2005, issue 6, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, for the publication of Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, edited by Caroline Turner |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Clark, C., 2003 “When the alternative becomes the mainstream: operating globally without national infrastructure”, in Cemeti Art House, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, 1988-2003, Yogyakarta, Cemeti Art House, p.122. Clark has continued an association with Cemeti Art House since being on the Indonesian selection committee for APT |

| ↑3 | Halim, H.D., 1999,. “Arts networks and the struggle for democratisation”, in Budiman Arief, B. Hatley et al ed., Reformasi: crisis and change in Indonesia, Melbourne, Monash Asia Institute. Also Vickers, A., 2005 A history of modern Indonesia, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp.195-198 |

| ↑4 | Turner, C., ed., 2005, Art and Social Change: Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, Pandanus Books, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, p.211 |

| ↑5 | Astri Wright, 1999, “Thoughts From the Crest of a Breaking Wave”, AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia, catalogue, Hugh O’Neill and Tim Lindsay, (eds) Indonesian Arts Society, Melbourne, p. 49 |

| ↑6 | Lucy R. Lippard, “Trojan Horses: Activist Art and Power”, in Brian Wallis, ed., 1984, Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, p.341 |

| ↑7 | Halim, HD, 1999, ibid, p.287 |

| ↑8 | Asmujo Jono Irianto, 2000, “An Unsettled Season, political art of Indonesia”, Art AsiaPacific, No. 28, p. 82 |

| ↑9 | Miklouho-Maklai, Brita, 1991, Exposing Society’s Wounds: Some Aspects of Contemporary Indonesian Art since 1966, Adelaide, The Flinders University of South Australia, Discipline of Asian Studies, p.100 |

| ↑10 | Supriyanto, discussing Lippard in Supriyanto, E., 1994, “Listening Once More to Lost Voices”, catalogue essay for FX Harsono’s exhibition at Gedung Pamer Seni Rupa Depdikbud (The exhibition space of the Department of Education and Culture, later the Galeri Nasional), publisher unknown, p.17 |

| ↑11 | Wright, Astri, 1999, op.cit., p.50 |

| ↑12 | Note, for example, the anthology, Budiman Arief, et al. 1999, Reformasi : crisis and change in Indonesia. The three main sections cover the economic crisis, the political crisis and ‘other dimensions’, which includes ‘Cultural expression and social transformation’. It is regrettable that ‘cultural activities’ are actually listed as: ‘literature, theatre arts, music and painting’, when experimental media and installation art was the significant form of visual art expressing socio/political themes |

| ↑13 | Ross Gibson, “Aesthetic Politics” in Queensland Art Gallery and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, 2006, The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art 2006, Brisbane, QLD., Queensland Art Gallery, p. 23. Nicholas Bourriaud, French curator and critic, developed the concept of relational aesthetics in the catalogue for the exhibition, Traffic, in 1995, see, Bourriaud, N. 2002, Relational aesthetics. [France], Les presses du reel |

| ↑14 | Ross Gibson, “Aesthetic Politics” in Queensland Art Gallery and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, 2006, The 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art 2006, Brisbane, QLD., Queensland Art Gallery, p.23. Nicholas Bourriaud, French curator and critic, developed the concept of relational aesthetics in the catalogue for the exhibition, Traffic, in 1995, see, Bourriaud, N. 2002, Relational aesthetics. [France], Les presses du reel |

| ↑15 | Virginia Matheson Hooker and Howard Dick, 1993, Culture and society in new order Indonesia, Kuala Lumpur, New York, Oxford University Press, p.5 |

| ↑16 | Quoted by Enin Supriyanto in “Reformation, Changes and Transition, Indonesian contemporary visual arts 1996 – 2006”, in Bollanee, Marc and Supriyanto, Enin, 2007, Indonesian Contemporary Art Now, SNP Editions, Singapore, p.33 |

| ↑17 | The details of this action by Semsar’s are covered more fully by Brita Miklouho-Maklai, in, Exposing Society’s Wounds: Some Aspects of Contemporary Indonesian Art since 1966, Adelaide, The Flinders University of South Australia, Discipline of Asian Studies, 1991, p.95 |

| ↑18 | Purnomo, S., 1995, ibid, p88 footnote |

| ↑19 | A. Junaidi, “Semsar, the rebellious artist”, The Jakarta Post, February 24, 2005, and Wahyoe Boediwaedhana, ” Semsar’s dream stays alive, despite his death”, The Jakarta Post, February 25, 2005, reproduced in “Semsar in Memorium”, Javafred, http://eamusic.dartmouth.edu/~gamelan/javafred/rd_semsar_mem1.htm accessed 09/10/06 |

| ↑20 | Heryanto, A., 1993 Discourse and State-Terrorism a case study of political trials in new order Indonesia 1989-1990, Anthropology, Melbourne, Monash University, PhD thesis, unpublished, p.3 |

| ↑21 | Laine Berman, “The Art of Street Politics”, in O’Neill, Hugh and Lindsey, Timothy,1999, AWAS! : recent art from Indonesia, Melbourne, Indonesian Arts Society, pp.75-77 |

| ↑22 | Tom Plummer, “Agung Kurniawan: ‘My main theme is violence’”, Inside Indonesia 50: Apr-Jun 1997 |

| ↑23 | Agus Suwage, c. 1996, This room of mine, The Lontar Foundation, Jakarta |

| ↑24 | Urbanization stood at 41% in the census taken in 2000, note figures quoted from Badan Pusat Statistik, http://www.library.uu.nl/wesp/populstat/Asia/indonesg.htm accessed 19/10/06 |

| ↑25 | Tom Plummer, quoting Moelyono in, “Art for a better world”, Inside Indonesia No 53, January – March, 1998, p.26 |

| ↑26 | Moelyono interview, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta |

| ↑27 | Moelyono, “Seni Rupa Kagunan: a Process”, in Schiller, J. W. and Martin-Schiller, B., 1997, Imagining Indonesia : cultural politics and political culture, Athens, Ohio, Ohio University Center for International Studies, p.122 |

| ↑28 | Schiller, 1997 ibid., pp.122 – 126. Tayub is a form of dance where men are invited to dance with a professional female dancer. A Kris is a wavy-edged knife, sometimes considered sacred |

| ↑29 | R. Fadjri, “Moelyono’s art invites dialog on social issues”, The Jakarta Post, Sunday May (date unknown) 1997, p.14 |

| ↑30 | Hasan, A., 1998 “Moelyono dan Seni Rupa Penyadaran”, Galeri Lontar, Jakarta. An interview between Asikin Hasan, curator at Lontar Gallery, with Moelyono for his exhibition, translated by Mien Joebhaar, 31/08/01, p.7. Pak, abbreviation of Bapak, literally ‘Father’, but interpreted as an honorific, or ‘Sir’ |

| ↑31 | Biografi in Moelyono, 1995 Art Conscientization, The Reflection of the Wonorojo Dam Project, ARX 4 22 March – 16 April, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts WA |

| ↑32 | Freire’s work was published in Indonesian as Pendidikan sebagai praktek pembebasan, or Education, as a practice of freedom, see Paulo Freire, 1984, Pendidikan sebagai praktek pembebasan, Jakarta, Gramedia |

| ↑33 | Schiller, 1997 op.cit., p130 |

| ↑34 | See Vickers, A., 2005 op.cit., pp. 193 – 194. Vickers describes the variety of experiences incurred under the transmigrasi program. Few transmigran prospered |

| ↑35 | Haryono, Endy and David, 1990 “Moelyono: art and social transformation”, Inside Indonesia, No. 25, Dec. 1990, pp.29-30 |

| ↑36, ↑37, ↑43 | Interview, Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta |

| ↑38 | Schiller, 1997 op.cit., p.134 |

| ↑39 | Hasan, A., 1998 op.cit., p.9. Recognition by the bureaucracy allowed a village to receive government funding for building facilities from such programs as INPRES, the Instruksi Presiden program |

| ↑40 | Schiller, 1997 op.cit., p. 135 |

| ↑41 | R. Fadjri, “Moelyono’s art invites dialog on social issues’, The Jakarta Post, Sunday May (?) 1997 |

| ↑42 | Haryono, Endy and David, 1990 op.cit. |

| ↑44 | Benjamin Waters, “The Marsinah Murder”, http://www.asia-pacificaction. org/southeastasia/indonesia/publications/doss1/marsinah.htm accessed 13/10/06; also version printed in Inside Indonesia No. 36, 1993. The protest was a consolidation of all the current debates concerning freedom of expression, workers rights and the safety of female workers. A month after her death, representatives of twenty-seven NGOs and human rights groups as well as other prominent people had formed the Komite Solidaritas Untuk Marsinah, the Marsinah Solidarity Committee or KSUM, to pressure the authorities for an enquiry and to reinstate the sacked employees. |

| ↑45 | Ewington, J., 1994 “The exhibition that never opened”, Art and AsiaPacific (Australia) 1 (4): 34 |

| ↑46 | It is understood that the spontaneous komentar often acts as safety valve for the expression of opinions suppressed by manners or authority, while the diskusi is a more organized discussion often after an exhibition opening |

| ↑47, ↑48 | Interview Moelyono, 12/07/01, Yogyakarta |

| ↑49 | ARX 1995, Torque, Perth, Western Australia, Australia & Regions Artists’ Exchange. The Indonesian artists were: Moelyono, Arahmaiani and Agoes Hari Rahardjo (Agoes Jolly). The first ARX was held in September 1987 initiated by Praxis, then Western Australia’s Contemporary Art Space. The Sam Bung Foundation was established by Tom Plummer and Murdoch University colleagues for cultural exchange projects between Indonesia and Australia. Indonesian NGO and cultural workers travelled to Perth and took part in seminars, performances and exhibitions. In 2001 the Foundation was no longer operating owing to difficulty in obtaining sponsorship, (phone conversation, Tom Plummer). See Moelyono, 1995 Art Conscientization The Reflection of the Wonorejo Dam Project. ARX/4, Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts, WA |

| ↑50 | A full description is given in Hillyer, Vivienne, 1997 Moelyono / Praxis, unpublished submission for B. Arts (Visual Arts), Edith Cowan University W.A. p.8 |

| ↑51 | The exhibition was Tumpengan Kelapa, Ceremonial Coconuts at Galeri Bentang Budaya, Yogyakarta. The word for coconut, kelapa, is similar to the word for head, kepala, an association reinforced by the shape of the coconuts. The identified review was by R Fadjri, “Moelyono’s art invites dialog on social issues”, The Jakarta Post, May 1970 |

| ↑52 | Adi Wicaksono, “Moelyono”, in Queensland Art Gallery, 1999 Beyond the future : the third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, South Brisbane, Qld., Australia, Queensland Art Gallery, p. 64 |

| ↑53 | Turner, C. ed., 2005 op.cit., p.208 |

| ↑54 | Moelyono, interview, Tulungagung, 10/05/05 |

| ↑55 | Schiller, 1997 ibid, p.130. Also in Marcel Thee, “Evoking Memories of 1965 in Indonesia”, September 12, 2009, The Jakarta Globe. Hendro Wiyanto, who curated Moelyono’s exhibition in Jakarta in September, 2009, titled, Topografi Ingatan or Memory Topography, reported similar concerning Moelyono’s position in relation to his work |

| ↑56 | Interview FX Harsono, Jakarta, 26/06/01 |