An appreciation of the role of curators was developing as the result of contact with international exhibitions of Asian art and the transition of Indonesian contemporary art from the local to the global was facilitated by the development of curatorial practice in Indonesia. It was the curator that physically and intellectually made the transition from the local art scene to the global exhibition and it was the curator who defined the artwork and attempted to insert Indonesian contemporary art into international art debates.

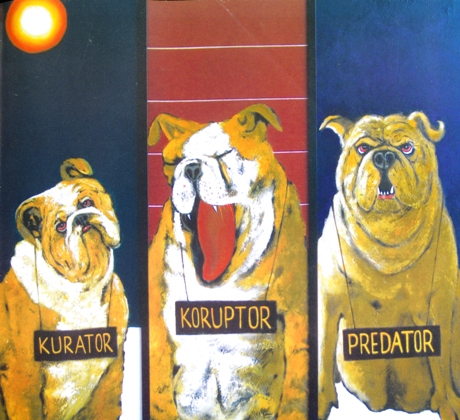

Yet once again the Indonesian version of a curator was conditioned by the lack of state infrastructure and public support for modern and contemporary art. There were no institutions to provide regular employment so that few Indonesian curators have been sufficiently secure to function independently from the art market. The distinctive category of kurator independen emerged: an independent curator who was not attached to any particular gallery or institution and who developed a career by a variety of art – related activities, ranging from organising festivals to writing art reviews on demand.

Curatorial practice emerged in Indonesia more or less at the same time as contemporary art was breaking from the constraints of the modern. Contemporary art, with its emphasis on content rather than aesthetics, required research to place a work in context. Yet although most curators began as academy – educated artists, there was no training in curatorial practice and barely any art history or theory in the curriculum. The majority were, therefore, self taught.

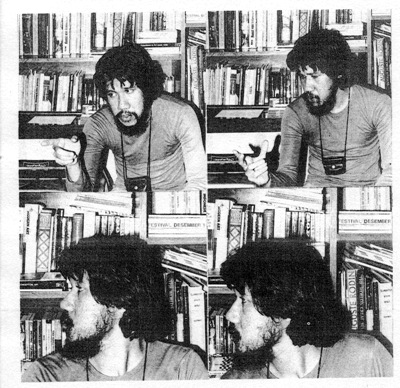

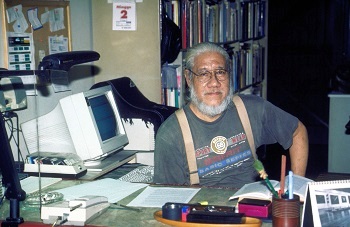

The first Indonesian art curator with an international profile and still the best known is Jim Supangkat who, like most Indonesian curators, began as an artist but gravitated towards art activism and art writing. Supangkat initially was alone in theorizing the concept of an Indonesian Modernism as distinct from a universal and Western – based Modernism. He proposed, for example, a theory of multimodernism that would allow space for a distinctive Indonesian form of Modernism. His curatorial career expanded in the 1990s and he was increasingly invited to represent Indonesian art overseas. He effectively became the public face of Indonesian contemporary art curatorship in an international context.

Curatorial Practice in general

In the West the role of curator had grown significantly in the course of the 20th century and was recognised as one of a number of elements that could influence value and meaning in a work of art. Today many Western tertiary institutions offer courses in curatorial practice, courses that are usually post graduate and emphasise the connection between “the theoretical side of art history as a university discipline and the practicalities of curating cultural objects and presenting them to the public”, as was stated for course studies in art history and curatorship at the Australian National University.[1]Australian National University, Art History, Curatorship and Museums,

http://info.anu.edu.au/StudyAt/_Arts/Undergraduate/Plans/_ARTSMARTC.asp accessed 09/04/07

The dominance of the author as the sole source of meaning in a text, or in the case of art, the artist as the source of meaning in an artwork, was challenged by the French school of philosophy and in particular, Roland Barthes in his essay, Death of the Author. Influenced by Post structuralism and other theories, the artist and artwork were seen in a wider context.

Janet Wolff, in her work, The Social Production of Art, identified a range of people who may influence a work of art:

“Even where artistic production is a more ‘individual’ activity, as in painting or writing a novel, the collective nature of this activity consists in the indirect involvement of numerous other people, both preceding the identified ‘act’ of production (teachers, innovators in the style, patrons, and so on) and mediating between production and reception (critics, dealers, publishers).”[2]Wolff, J., 1981, The Social Production of Art, Macmillan Education, p.118

The original role of a curator as a conservator, to preserve and display the collections in an institution, expanded to encompass the context of an art object or the way in which concepts or circumstances beyond the artwork influenced and conditioned it. Meaning in a work of art often remains contested ground and perceptions change according to context. An example of this is Mella Jaarsma’s first jilbab artwork made from frog skins. The frog skins were chosen because they were part of Chinese cuisine and not considered halal for a Muslim, a pointed comment on cultural attitudes at a time when ethnic Chinese were particular targets of prejudice in Indonesia. Shown in Australia, those viewers who were ignorant of recent Indonesian history and these cultural sensitivities, associated the frog skins with environmental issues and the disappearance of frogs due to habitat degradation.

The curator increasingly wielded power by interpreting a work, identifying significance and being both the initiator and writer of art history. Again this role is not fixed and, if a curatorial career extends into other areas such as critic, collector or teacher, a conflict of interest may arise. Receiving payment as an art advisor, for example, may influence the impartial judgment of a work of art.

The power that some curators were wielding generated criticism. David Sylvester, a British curator, wrote:

“… in contemporary art, the curator has become a far grander figure, a super-curator who uses the position of curating exhibitions, selecting and presenting contemporary art, to manipulate taste, powerbroke careers of artists and become as much of a star as the artists themselves. At its best, curating is an art of juxtaposition, scholarship and display that brings old art to life and makes new art surprise us all the more. At its worst, the curator stands between us and the art (like the texts on the wall).”[3]Sylvester, D., “Curator and Critic London,” Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday November 20, 1999

Curators were initially associated with institutions and carried clout according to the importance of that institution, but some detached themselves from their home establishments and became ‘freelance’ or independent. The example most cited of this kind of curator is Harald Szeemann from Switzerland who left his personal mark on both the documenta and the Venice Biennale, amongst other major exhibitions.

Such curators become gatekeepers of cultural activities. Through their contacts and ability they influence preferences in the area of their discipline and further, influence public taste. By their selection, a curator also influences the reputation and career of an artist. These curators became gatekeepers both locally and from the local to global art interests. In Indonesia, Jim Supangkat was one of the first to understand the role that independent curators were playing in the West. Under the influence of Sanento Yuliman in his concept of curatorial practice in Indonesia, Supangkat sought to base his judgment on research rather than personal preference as was common at the time.

Indonesian curatorial practice

By the 1990s there was an increasing awareness in Indonesia of the role that an art curator can play in relation to an artist’s career. The demand for curators came initially from the commercial sector with a growing number of galleries needing art writers, commentators or critics to write articles for exhibition catalogues, and as a result, art writing developed into a profession. There was, though, no tradition of impartial art criticism: according to artist and gallery director, Agung Kuniawan, ‘it is not Javanese to criticize’.[4] Interview, Agung Kuniawan, Yogyakarta, 3/6/02 Gallery owners and artists paid critics to write about their exhibitions and, as Patrick Flores, Associate Professor of the University Philippines Department of Art Studies, observed, in Indonesia “… even the most frankly commercial enterprises are propped up by curatorial gravitas”[5]Patrick D. Flores, 2006, Past Periphery: Curation in Southeast Asia, unpublished research paper and excerpt from a manuscript for his book, Past Peripheral: Curation In Southeast Asia, Singapore, 2008

Art writers and curators themselves have written of the problems that exist for Indonesian curators. According to Rizki A. Zaelani, the two roles, that of curator and critic, have been combined in the public mind without an understanding of the different conventions that pertain to them.[6]See Rizki A Zaelani, “Hipotesis Kurator[-ial]” (Curatorial Hypothesis), and other essays on the subject in, ‘Focus’, Visual Arts, Vol. 10, December 2005 – January 2006, pp. 34-48

Rifky Effendy wrote,

“In the Indonesian art community, ‘curator’ is a relatively new ‘phenomenon’ and is often confused with everything from organizing (an exhibition) to coordinating an art event.”[7]Statement for the Goethe-Institut workshop, The Multi-Faceted Curator, 2006, http://www.goethe.de/ins/id/prj/mfc/cur/eff/enindex.htm accessed 10/08/2006

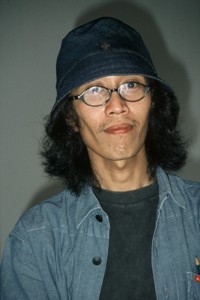

Indonesian art criticism, according to Enin Supriyanto, (left) is ‘commentary’ based on personal observations and preferences, not the result of a process of self-examination.[8]Supriyanto, E., 2003, “Infrastruktur dan Proses Rezimentasi Seni – Wawancara dengan Enin Supriyanto”, Infrastructure and the Art Regime – Interview with Enin Supriyanto, in … Continue reading Personal preference expressed in writing has too often descended into personal invective, as was seen in the debates published in newspapers after the exhibition of Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru and the more recent closure of the CP Biennale, a project of the Center Point Foundation.[9]In 2001 Jim Supangkat, with the Indonesian/Chinese entrepreneur, Djie Tjianan, established the CP or Center Point Foundation. Supangkat became the director of a CP Artspace in Jakarta and briefly in … Continue reading

Further confusion arose when some gallery owners were called, or called themselves, ‘curator’ when selecting and mounting exhibitions in their galleries. The more respected of these included Edwin Rahardjo of Edwin’s Gallery in Jakarta and Mella and Nindityo at Cemeti. The lack of formal training in curatorial practice meant that art writing and criticism was by writers with no training and often little experience in the field. Art school graduates gravitated to writing about art for a variety of reasons, from assisting their circle of friends in the art world to arguing theoretical positions in print, or simply because they need more strings to their bow to survive financially. When curatorial practice is not the sole or even main occupation of graduating artists, obviously the standards of analysis are variable.

Artists often express mixed feelings about curators, some preferring to work with curators with a visual arts background whereas other artists would avoid them entirely but for the writing of a catalogue preface. A certain amount of cynicism about Indonesian curators was reported in a workshop organized by the Goethe-Institut Indonesien in Jakarta and Bandung in March 2006 titled, The Multi-Faceted Curator.

“If you want to become a curator in Indonesia, it is easy. By getting a little knowledge on sculpture theory, flipping through photographs of paintings and being able to write editorial notes in catalogues, you are immediately a curator. This is an indication of how a curator can take advantage of, or be taken advantage of by gallery owners.”[10]Putu Fajar and Arcana Dahono Fitrianto, “Jalan Pintas Kurator Indonesia”, Indonesian Curatorial shortcuts, Kompas, Minggu 19 Maret, 2006, documents provided in pdf format at … Continue reading

If art history and theory is addressed at all in the art academies, it is only given sketchy treatment. Dwi Marianto has described in some detail the haphazard teaching approach at ASRI in the 1970s that still exists today. He wrote that few students were interested in theoretical courses as it conflicted with their romantic notion of an artist, teaching did not encourage the development of an individual critical approach and attendance was only to meet course requirements.[11]Marianto, Dwi M., 1995, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, PhD thesis; unpublished, University of Wollongong, pp.130 – 136 It was reported that the Western art theory curriculum dating from the 1950s was still in place, that it required reading books in English, which few students could do, and there was neither money nor encouragement for theoretical research.[12]This was reported by Setianingsih Purnomo, who obtained a Master of Arts (Hons.) from the University of Western Sydney, Art History department, 1995 and worked with the now defunct museum of the … Continue reading As seen when the art academies in Yogyakarta and Jakarta were founded, the Sanggar, or studio tradition was influential and it continued to be so. The Sanggar reiterated the central and ‘romantic’ role of an artist who would gather a group of students in his studio for informal teaching according to his personal preferences, the emphasis being on practical studio experience rather than a theoretical basis for a work of art.

Theoretical debate, when it did occur, was usually outside formal teaching in art schools, so that knowledge filtered through improvised systems and in a non-academic manner. A small group of curators developed around ITB because lecturers, such as Asmudjo Irianto, Rizki Zailani and Agung Hutjatnikajennong, were interested in theory through their own activities as writers and curators, and they introduced ideas to their students. They set up an independent discussion group called the Klub Mancing, the Fishing or Angling Club, that met once or twice a month. Its influence was limited to the dedicated and without theoretical background or a tradition of debate amongst the students, the leaders dominated discussion. As one participant said, “I remember coming to the club once and just sitting there feeling dazed and confused, because that day they were discussing something about Deleuze and Guattari.”

Without institutional support, art history is written in an ad hoc fashion and important texts are missing. Most significant amongst these is the doctoral thesis of Sanento Yuliman, Genese de la Peinture Indonesienne Contemporaine, le role de S. Sudjojono, that was submitted in Paris in 1981 but has not been translated from French into Indonesian. It is another example of Indonesian art history, along with major Indonesian contemporary art works, that reside in institutions outside Indonesia.

The lack of an arts infrastructure in Indonesia and limited teaching of art theory has resulted in the absence of agreed terminology for theoretical debate, according to Asmudjo Irianto:

“In fact, such a situation prevails in most non- Western countries in which modern art infrastructures are undeveloped in comparison to the West. As a result, the development of relevant discourses is hampered and sporadic. The main result of this is the lack of agreed and theorized values (a discourse) amongst artists, collectors, critics and art historians.”[13]Asmudjo Jono Irianto, 2001, “Tradition and Socio-Political Context in Contemporary Yogyakartan Art of the 1990s”, in Outlet, Yogyakarta within the Contemporary Indonesian Art Scene, the Cemeti … Continue reading

Alternative art spaces such as Cemeti have provided the arena for testing controversial and experimental art concepts, as has been Cemeti’s stated intention since its foundation.[14]Saut Situmorang, “WANTED: Indonesian Art Critic(ism)”, in Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, 1988-2003, Yogyakarta, Cemeti Art House, p.188 Galeri Lontar, associated with the Komunitas Utan Kayu in Jakarta has occasionally provided a similar forum as has ruangrupa, with their sporadically published journal, Karbon, in particular. Of them all it has been IVAA, the Indonesian Visual Arts Archive, formally the Cemeti Art Foundation, that set out to mount seminars and debates on central issues for the arts.

The analysis of the role of curator is limited and there are few publications on the subject. Most of the presently practicing cuators graduated first as artists and one, Asmudjo Irianto, continues to practice as an artist. Enin Supriyanto was studying art at ITB in the late 1980s but did not graduate as he was imprisoned for three years for student activism.[15]Interview, Enin Supriyanto, 2009 His career includes being part of the curatorial board of Bentara Budaya, the Kompas newspaper’s exhibition space in Jakarta, and editor of the new Visual Arts magazine. Hendro Wiyanto graduated as an artist from ISI, Yogyakarta, in 1986 but then studied philosophy at the Driyarkara School of Philosophy, Jakarta, and at the Faculty of Literature at the University of Indonesia, (UI).[16]The Multi-Faceted Curator, 2006, ibid, ‘Observers’ Like many, he said he began writing essays and articles for friends who were artists because their exhibitions needed art writing. In 2002 he curated the exhibitions of both Dadang Christanto and F.X. Harsono and in 2004 the major exhibition of Heri Dono’s work at Nadi gallery. He has a good reputation with artists because of his perceptive analysis that is considered not too theoretical, but he is also considered by the younger generation to be a curator for the older, more established artists. It was difficult to make a living as a writer–curator, he said, but his wife works in an office, implying that provided a steady income.[17]Hendro Wiyanto, personal communication, 13/5/02

Of the currently recognized curators, most call themselves kurator independen. A few for whom curating is their main activity may develop a relationship with a particular commercial gallery. Selasar Sunaryo, the gallery owned by the artist Sunaryo, employs Agung Hujatnikajennong more or less as a full time curator, but this was probably the first time such an arrangement has occurred and remains rare. Hendro Wiyanto has curated a number of significant exhibitions and written catalogues for Nadi Galeri[18]See Galeri Nadi website: http://www.nadigallery.com/previous_exhibition.htm accessed 09/04/07 and Cemeti Art House, when they were able to gain short term grants, have employed part time curators. The most important source of employment for curators in the West, museums or government institutions, has no equivalent in Indonesia. Without the objective forum that government-funded institutions can provide, Indonesian curators are much more subject to market forces.

For Jim Supangkat there are important constraints on the role of kurator independen. He said he had stated to everyone who worked with him that curators should have ethics and that they should either “… be a curator or be a businessman.”[19]Jim Supangkat, interview, Bandung, 24/04/2005 Clearly a curator being paid to act as an advisor in the art market, promoting certain artworks and supporting certain exhibitions is not truly independent. Yet the opportunity to construct a career outside the booming art market is extremely difficult and there is considerable pressure to oblige commercial interests. A sponsor or commissioning gallery may withdraw support if market returns are not forthcoming. As the report on the Goethe Institute workshop stated “… the art object becomes a market object” and “In the end, the success of an exhibition is measured by the total number of paintings sold.”[20]Putu Fajar and Arcana Dahono Fitrianto, 2006, ibid

Supangkat also said that very few curators have been able to train or gain museum experience outside Indonesia and even if they could obtain training abroad, it was not a practical solution for developing local art history discourses. All Asian countries, apart from China and Japan, lack courses for curatorial training.[21]Interview, Jim Supangkat, Jakarta 02/07/2000. He reported that there are two universities, both in the Philippines offering art history and he believed there was one course offered in India. See also … Continue reading Without scholarships or government assistance, it was only the students from a comfortable socio-economic background who could afford full fee-paying courses overseas.

Among the first few Asian curators who had been educated abroad were Apinan Poshyananda from Thailand, T. K. Sabapathy from Malaysia and Supangkat himself gained postgraduate training in the Netherlands. By the late 1990s Amir Sidharta and M. Dwi Marianto had received qualifications overseas: Sidharta graduated in Architecture from the University of Michigan in 1987 and then, as a Fullbright scholar, graduated in Museology from George Washington University in 1993.[22]Informasi Kontributor, contributor information, Visual Arts, Oktober/Nopember, 2004, p.111 Marianto received his master degree in Printmaking from Rhode Island School of Design, Rhode Island, USA (1988) followed by a PhD. in Creative Arts from the University of Wollongong, Australia in 1998.

In 1994 Supangkat identified a range of problems facing the Indonesian art community including the lack of books on modern and contemporary Indonesian art, a national gallery, documentation, and that art critics should be knowledgeable about theories, aesthetics and art history.[23]Supangkat, J., 1994 The Critic At large, Asian Art News, 4 (issue no 2), p.15 He was optimistic that there would be change, yet the Galeri Nasional that developed between 1995 and 1999 is not what Supangkat envisaged and the teaching of art history and theory in the art schools was still unsupported by both staff and students.

According to Rifky Effendy, the real education for Indonesian curators came from global contacts through international exhibitions and residencies rather than academic training or museum experience.[24]Rifky Effendy, “A General View on Today’s Art Infrastructure”, Visual Arts 6, April/May, 2005, p.22, quoted in Patrick Flores, ibid, p.84 In the 1990s, with the increasing interest in Asian art in international biennales, networks of information were forged through conferences, residencies and exhibitions that contributed greatly to curatorial experience. The Japan Foundation supported two researchers or curators a year in three-month residencies in Japan and in 1998, Rizki Zaelani was selected as the curatorial resident at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum. Asialink, in association with the Kelola Foundation in Indonesia, provides internships of 3-4 months duration in Australia in arts management.[25]Kelola was established in 1999 in Solo and is now Jakarta-based. Website: http://www.kelolaarts.or.id/maganginternasional-e.php accessed 08/08/06, and http://www.kelola.or.id/ accessed 11/03/2012 Through their Indonesia-Australia Arts Management Program, they assisted Rifky Effendy in 2000 to work with the Adelaide Festival in South Australia and Artspace in Sydney. In their ‘Briefing notes for host organizations’, Asialink recognized the lack of arts management training and declared that “The residencies are part of an overall strategy for assisting the Indonesian arts community to develop infrastructure”. Rifky subsequently became a Fellow of the Asian Cultural Council and was a resident curator in the International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York in 2004.

Rifky’s own career as a kurator independen has been an interesting and diverse one, involving a number of projects. He graduated from ITB as a ceramic artist and has been associated with galleries including Cemara 6 and the now defunct Galeripadi in Bandung. He has written for a range of newspapers and art magazines, established a blog and was the founding director in 2001 of the Bandung Art Event.[26]Rifky Effendy‘s Curriculum Vitae on the Goethe Institut website http://www.goethe.de/cgi-bin/goethe-print/print-url.pl?url=http://www.goethe.de/ins/id/prj/mfc/cur/eff/enindex_pr.htm accessed … Continue reading

Overall, Enin Supriyanto considered that Indonesia was ten to fifteen years behind Europe in curatorial practice. He would support the establishment of an independent curatorial educational body to avoid the continuous commercial exploitation of art that had so often been noted. As it is, only established curators, such as Jim Supangkat, Dwi Marianto, Suwarno, (a writer/curator and lecturer from ISI), and Hendro Wiyanto, are well paid for mounting exhibitions. Senior curators may receive approximately Rp10 to Rp15 million (AUD$1400 – $2100) but the younger curators would not be paid as much.[27]Conversation, Carla Bianpoen, Jakarta, 22/04/05. These figures would have applied at that time According to Rifky Effendy, in a society without insurance, unemployment benefits or welfare, young curators starting out are dependent on the support of their families or friends to fill gaps in employment. On the other hand, the arts in Indonesia, he said, were a wide-open field in which there was room to move, unlike Australia, where there is much competition for positions and grants. Some curators actively like the ability the Indonesian art scene provides to move between different roles, while others, as has been seen, are concerned by the influence of the art market and the potential conflicts of interest that arise.[28]These opinions were expressed in conversations with Rifki Effendy, Bandung, 06/07/00, Aminudin Th. Siregar, known as Ucok, Canberra, 12/08/2011 and as previously mentioned, an interview with Jim … Continue reading

Some art writers and curators have moved entirely into the commercial area, most notably Amir Sidharta and Agus Dermawan T., who, in 1984 when the painting boom took off, became a supplier for the commercial galleries and took commissions. Amir Sidharta has contributed to many Indonesian and American journals and published books on artists. He was to be curator of the art museum at Universitas Pelita Harapan, but the Lippo Bank, who had originally planned to develop the museum with their collection, ended by auctioning it in the heated art market.[29]Interview, Amir Sidharta, Jakarta, 25/06/01. Some years later Sidharta refuted this statement, 20/05/20, stating that the Lippo collection is still intact in the museum’s collection and the … Continue reading Sidharta was involved in these art auctions, became a director of the Larasati auction house and has now opened his own auction house, Sidharta Auctioneer, which held its first auction on December 3rd, 2005.[30]Asian Art News, 2006, “New Player on the Block”, Asian Art news, pp. 84 – 85

A younger generation, most of whom graduated after 2000, is developing an art writing and curatorial practice based on a similar model to that of Supangkat. These include Aminudin TH Siregar, known as Ucok, Mikke Susanto, Sujud Dartanto and Alex Supartono. Ucok, for example, is a curator for Galeri Soemardja, the exhibition space for the School of Fine Art and Design at ITB, and has written on issues of art history and theory. He has had residencies in New York and Germany and in 2006 a six-week residency as visiting curator with the Gertrude Contemporary Artspace in Melbourne, Australia.

In reality there are very few who could truly be called independent curators if Jim Supangkat’s definition of ethics is accepted, that is, separating commercial interests from curatorial practice. For a country of over 220 million people, the contemporary art world is small and within it there are possibly no more than fifteen who operate as professional curators along Supangkat’s lines, which includes those mentioned here.[31]Again I have relied on word-of-mouth. In 2001 when interviewing Amir Sidharta, 25/06/01, Jakarta, I asked him to list who, in his opinion, were the significant curators of contemporary art in … Continue reading When there are no institutions providing full time permanent employment for curators and young curators are not well paid, working with commercial galleries can be a question of economic survival. As a result in Indonesia the accepted boundaries of Western curatorial practice, both ethically and economically, have of necessity become blurred.

Curating and art writing for and by women

In 2006 the glaring absence in curatorial practice was that of women. Carla Bianpoen, writing in the Jakarta Post, stated that 12 of a total of 18 participants in the Goethe Institute workshop, the Multi-Faceted Curator, were women, but they were all from overseas. This indicated the considerable participation of women in international curatorial practice but the absence of Indonesian female participants, about which Bianpoen made no comment.[32]Carla Bianpoen, “The multi-faceted curator in question”, The Jakarta Post, April 10, 2006

There are, though, a few women involved in art writing or curating. These include: Farah Wardani, now director of IVAA, Wulan Dirgantoro, the only Indonesian curator, either male or female, to gain qualifications specifically in curatorial practice, and Inda Citraninda Noerhadi, the daughter of Professor Toeti Heraty, who has managed Cemara 6 gallery in Jakarta since 1993 on her behalf. [33]Farah Wardani graduated from Trisaki University in 1998 and gained a Masters in the History of Art from Goldsmiths College, London 2001. She taught theory at Universitas Paramadina, Jakarta, and has … Continue reading

Carla Bianpoen has been an independent journalist, writing especially in English language papers such as The Jakarta Post and the British Observer since retiring from the World Bank where she worked in gender-related issues. Now in her seventies, Bianpoen continues to conduct a one-woman crusade for the recognition of women artists. In the publication she co-edited, Indonesian Women, The Journey Continues, she stated that,

“Until recently, women artists were almost left out of art representations of national significance,”

and followed with a devastating list of major exhibitions held between 1990 and 1997 that either excluded or gave minimal representation to women.[34]Carla Bianpoen, “Indonesian Women Artists, Between Vision and Formation”, in Oey-Gardiner, M., and Carla Bianpoen, eds., 2000, Indonesian women : the journey continues, Canberra, Australian … Continue reading

Bianpoen, who is also a senior editor and contributor at the Singapore-based C-Arts magazine, was the primary mover behind the book, Indonesian Women Artists: The Curtain Opens. The book, co-authored with Farah Wardani and Wulan Dirgantoro, was launched in conjunction with an exhibition of women artists titled, Intimate Distance, and held at the Galeri Nasional, Jakarta, in August, 2007. Women art activists, such as Bianpoen and Toety Heraty, have focused on ‘recovery projects’ that seek to reclaim the careers of women artists from obscurity or raise the profiles of contemporary women artists. The inference is that by holding the work of women up to public view, their intrinsic value will be recognized, but the complex causes of their obscurity is not examined. The investigation of women artists in terms of feminist theory is yet to be undertaken in Indonesia.

The lack of female curators has contributed to a limited curatorial involvement in issues significant for women. Gender debate is not a priority in the male-dominated art world of Indonesia and there is, as a result, a form of unthinking discrimination amongst male curators. Some of the previously mentioned curators are aware of a growing tide of interest in women’s issues and feminist theory amongst female art students, but they don’t consider it their issue. The most common response, when female concerns in the visual arts are discussed with male curators, is that everyone in Indonesia is underprivileged, not just women. They consider that if women were underprivileged, they were more likely to be found in traditional areas and would not be modern women, thereby disregarding the discrimination against women in urban areas.

Men speak for women in Indonesian visual arts. Dwi Marianto was the lone male selector of artists for the exhibition, Text and Subtext: Contemporary Art and Asian Women, curated by Binghui Huangfu for the Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore. In his catalogue essay he stated somewhat ironically,

“It’s important to write about Indonesian women artists in order to address the imbalance of Indonesia’s written art history.”[35]M. Dwi Marianto, 2000, “Recognising new pillars in the Indonesian Art World”, Text and Subtext, Exhibition Catalogue, Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore, p.145

Hendro Wiyanto, writing the curator’s foreword for Night sCream, an exhibition of the work of six women artists at Galeri Embun January 2000, began by apologizing for his ignorance of women’s issues. His essay addresses the assumptions surrounding female beauty raised in the exhibition and mentions the artists’ interest in inequality between men and women, but fails to consider the social structures in Indonesia that militate against women and multiply the obstacles for their participation in the arts.[36]Wiyanto, H., 2000, Night sCream, Group Exhibition. The artists involved were Lenny Ratnasari, Anita Bilaningsih, Laksmi Shitaresmi, Regina Bimadona and Sekar Jatiningrum, Galeri Embun, 28 Jan – … Continue reading In another example Rifky Effendy curated and wrote the essay for the of Titarubi’s exhibition work, Bayang-bayang maha kecil, Shadows of The Smallest Kind, at Cemara 6 in 2004. He was considered to have framed the work with irrelevant theory and not addressed the concerns of the artist.[37]This was raised in the panel discussion that included Wulan Dirgantoro and Heidi Arbuckle, titled, ‘Gender, sexuality and artistic expression’, in the Indonesia Culture Workshop: Arts, Culture … Continue reading

Laine Berman, in the Indonesian conference session at APT/3, summarized the situation as an ‘urban Javanese male hegemony’. She wrote,

“Contemporary art is almost entirely limited to men in three centers – Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta” and this is “… enhancing the issues of inequality, including issues of a monopoly of the ability to define cultural and national identity.”[38]Low, M., C. Turner, et al., 2000, Beyond the future : papers from the Conference of the third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Brisbane, 10-12 September, 1999, Brisbane, Qld., Australia, … Continue reading

Clearly, if men continue to speak for women in the visual arts, not only is women’s artwork under-represented, but specific issues concerning 50% of the population do not get an equal exposure.

Jim Supangkat

The early 1990s marked a watershed in Indonesian art as curatorial practice developed and new forms of experimental art challenged modern art in Indonesia. Internationally, globalization in the fine arts took the form of large-scale international survey exhibitions. Few Indonesian curators were in a position to recognize the significance of these changes apart from Jim Supangkat who was the first Indonesian art writer and curator to enter this global world of contemporary art. He was the intermediary between the local and the global, a gatekeeper for international selectors of Indonesian art and for Indonesian artists exhibiting internationally. He was the role model as curatorial practice evolved in Indonesia and, although by the late 1990s other curators were developing international contacts, some on the basis of Supangkat’s recommendation, none has become as well-recognized. According to Carla Bianpoen,

“Jim Supangkat is the only one who can communicate and communicate on an international level”.[39]Bianpoen, who has greatly assisted my research, declined to be quoted on any opinion but for this one. Interview, Jakarta, 14/05/02

Jim Supangkat describes himself in his curriculum vitae as follows:

“Self-taught art historian born in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia in 1948. Married to a sculptor Altje Ully Panjaitan and father of two daughters. Hitherto worked as an artist, art lecturer and journalist. In 1990 began working as an independent curator in response to the lack of curatorial professionals in Indonesia and, due to ethical reasons, stopped working as an artist that same year.”

Supangkat is the product of a privileged family background under the Dutch colonial rule of Indonesia. He is ethnically Chinese and from a Christian background, although neither aspect was raised by him in interview. His great grandfather had a company in Yogyakarta that maintained the motorcars of the Sultan, and his grandfather became a Protestant Calvinist minister in the United States. His grandmother, “…a wonderful woman, a traditional woman, she was only educated for 3 years,” came in contact with a range of people in America and eventually became an American citizen. She was self- educated and introduced Supangkat at an early age to Steinbeck, Hemingway and Shakespeare, continuing to support him through his arts education by posting books and art magazines to him that were rarely seen in Indonesia, such as ARTnews and Art International. Both his parents received a Western education under the Dutch colonial rule before the Second World War and, on the recommendation of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, his father gained a place in a Surabaya medical school, the only institution training Indonesians as doctors. But although his father became an art collector, it is his grandmother he credits with the intellectual stimulus for his contemporary art practice.[40]The details of his personal history were provided by Jim Supangkat in interviews in Jakarta, 02/07/00 and Bandung, 24/04/2005.Note the discussion concerning the position of ethnically Chinese … Continue reading

Supangkat joined the Bandung Artists’ Studio in 1964 to study painting and continued with studies in architecture in 1969, eventually graduating with a major in sculpture from ITB in 1975. From the beginning he challenged the status quo of Indonesian art and enjoyed being provocative:

“As a student I started talking about contemporary art and my lecturers asked me: what is contemporary art? … I started making installations and the lecturers didn’t know what they were. I got this information from my grandmother in San Francisco and from magazines…”

He was concerned about the acute lack of Indonesian art history and theory in art education with students graduating only knowing Western art history. He said,

“… when you asked artists in their final exam: what do you know about Sudjojono, they would say: I don’t know anything. “

Between 1973 and 1975 he studied aesthetics with Dick Hartoko, a Jesuit priest, intellectual and the editor of the Catholic journal, Basis, which has been published from Yogyakarta since the 1950s. The more he moved towards the international art world, the more he explored international concepts of art theory.

Supangkat, as previously mentioned, played a significant role in Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru. He was an organizer, writer and participating artist from its foundation in 1975, when his art work was the focus of criticism, to its last collaborative exhibition in 1987, the Pasaraya Dunia Fantasi, Fantasy World Supermarket. In 1979 he edited a book of essays that included the manifesto of GSRB, a book that became in effect the historical record of the group.[41]Supangkat, J. ed., 1979. Gerakan seni rupa baru Indonesia : kumpulan karangan. Jakarta, Gramedia, his own essay was titled, “Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru”. All translations used from this publication … Continue reading Supangkat began to develop a theoretical position for an art movement that was a marked alternative to the current direction of Indonesian Modern art with its focus on aesthetic form.

Supangkat’s last activity with members of GSRB was an installation titled The Silent World for ARX, the Australian and Regions Artists’ Exchange in Perth in 1989. His various roles included medical journalism and he provided the research for this installation which concerned AIDS. Manikins similar to those he had used in Pasaraya Dunia Fantasi were used again to represent the powerlessness and isolation of people, in this case the victims of the disease. Before travelling to Perth for ARX, the installation was exhibited in Jakarta, where it was accompanied by a performance.[42]The Indonesian artists at ARX 1989 were Supangkat, Riyanto, Sri Mallela and Nuarta. A full description is provided in Miklouho-Maklai, 1991, ibid, pp.107-108. The significance of ARX projects is … Continue reading

In 1978 Supangkat had studied at the Psychopolis Vrije Academie in The Hague, Netherlands, which completed his education in art, architecture and the Philosophy of Art. In the 1980s his activities were focused on art writing and also lecturing in art philosophy, firstly at Trisakti University until 1984 and then in art history, criticism and philosophy at IKJ until 1993. At the same time he worked as an arts editor on Zaman magazine until 1985 and then as an editor in various areas of Goenawan Mohamad’s, Tempo magazine.[43]According to his C.V., Jim Supangkat was at different times during this period: the desk editor for art and architecture, international affairs, science and technology and health and behaviour, … Continue reading This experience is significant not only for the range of his writing and contacts that he made, but also because he was yet again associated with a politically active area of the arts and media.[44]See the history of Tempo in Steele, J. E., 2005, Wars within : the story of Tempo, an independent magazine in Soeharto’s Indonesia, Jakarta, Singapore, Equinox Pub., Institute of Southeast … Continue reading In 1994 the Suharto government banned Tempo and many of Tempo’s activities were forced to continue in clandestine through the activist group and ‘think tank’ at Komunitas Utan Kayu in Jakarta. While on the curatorial board of Galeri Lontar, part of the Komunitas, Supangkat remembers editorial meetings were held in secret behind a screen in the gallery exhibition space.[45]Interview, Jim Supangkat, Bandung, 24/4/05. Galeri Lontar and Komunitas Utan Kayu was discussed in more detail in Chapter 2.

Curatorial practice

In 1990 Supangkat attempted to establish an art centre in South Jakarta in conjunction with art writers, including Sanento Yuliman, and two well-known artists. The attempt was not successful but, Supangkat said, it caused him to consider the concept and role of a curator. This marked Jim Supangkat’s move into curatorial practice and in 1993 he ceased working in an editorial capacity for Tempo.

Supangkat developed his curatorial career in Indonesia and in the international forum concurrently. In Indonesia he has regularly been a judge for art prizes including the important Philip Morris Art Competition and has been the curator for biennales for Indonesian painting held in Yogyakarta and Jakarta. In 1993 he curated the Ninth Jakarta Biennale for the Jakarta Arts Council that introduced contentious issues and marked a major change in direction for Indonesian art.

Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX, The Ninth Jakarta Biennale

The Ninth Jakarta National Biennial for Indonesian art opened at the height of a public debate over Postmodernism in the newspaper columns of Kompas, Jawa Pos, Republika and Kalam. A new generation had emerged with ideals that differed from those of the previous generation for whom the priority had been resistance to colonialism and the creation of an Indonesian identity. The academic and activist, Ariel Heryanto, commenting on the spirit of the new generation, equated the ‘intellectual vogue’ for Postmodernism with the formation and political orientation of the middle classes and the radicalization of these, their educated children.[46]Dr Ariel Heryanto, academic and lecturer from Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana, Christian University Faithful to the Word, Salatiga, Indonesia, until 1996, a university with a reputation for … Continue reading

Previously the Jakarta Biennale had been known as the National Biennale of Painting, but by the mid 1980s more artists were working in alternative media such as video, performance and installation. At least half of a total of 60 artworks selected by Supangkat for the Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX were installation pieces. Supangkat claimed in his curatorial essay that: “This art is also recognized as Postmodern art”, on the grounds that the art used ‘alternative idioms’, that ‘the construction of formal elements’ was not a priority, that it addressed ‘radical’ issues and that it stood in opposition to the ideology of Modernism.[47]Supangkat, J., 1993, “Seni Rupa Era ’80”, in Pengantar untuk Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX, Visual Art in the 80s: Guide to the Ninth Jakarta Art Biennale, (Jakarta Arts Council?). Some 30 articles were written in the space of one month, December 1993 – January 1994, that debated the exhibition in the context of Postmodernism, and there were further essays in journals and books.[48]Hujatnikajennong, A., 2001, Perdebatan Posmodernisme dan Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX (1993-1994), The Debate of Postmodernism and the 9th Jakarta Biennale (1993-1994), unpublished thesis, Fakultas … Continue reading

The artists in the exhibition included Heri Dono, Mella Jaarsma, Nindityo Adipurnomo, Dadang Christanto, Arahmaiani, Agus Suwage, Dede Eri Supria, Anusapati, Eddie Hara and Krisna Murti. Some of the artists baulked at being defined in Postmodern terms, including FX Harsono and Semsar Siahaan. Harsono raised the question of interpretation and who controls ultimate meaning in a work of art, criticizing Supangkat’s curatorial premise for overriding “the opinions and thoughts of the artists which form the basis of their artworks.”[49]FX Harsono, “Biennale IX Seni Rupa Jakarta, Dominasi Baru Pascamodern”, harian Kompas, 16 Januari 1994, quoted in Hujatnikajennong, A., 2001 ibid. Semsar Siahaan placed a sign at the entrance to his installation which read: “You are entering the postmodern-gravitation-free area”, and he elaborated further in an article published in 1994 titled “Vehemently Opposed to Postmodernism in Contemporary Art.”[50]Semsar’s article, “Dengan tegas Menolak Postmodernisme dalam Seni Rupa”, Media Indonesia, 2 January, 1994, in Asmudjo Jono Irianto, Outlet, ibid, p.68, footnote. He rejected the Postmodern label as irrelevant to his work, which he said concerned ‘structural oppression’, and stated that to apply the label was an act of ‘intellectual snobbery’.[51]Semsar Siahaan dikutip H. Sujiwo Tejo, dalam H. Sujiwo Tejo, “Semsar, Pelukis Penggali Kubur”, harian Kompas, 11 Januari 1994, quoted in Hujatnikajennong, A. 2001, ibid. Hardi, another activist, concluded

“… this biennale is just to display progress in the Indonesian art world, that it hasn’t been left behind by the West.”[52]Hardi, “Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX: Sebuah Cangkokan Barat yang Mentah”, jurnal Horison 02/XXVIII, 1994, quoted in Agung Hujanikajennong, ibid, Chapter 4

The writer and lecturer, Tommy F. Awuy, contrary to Semsar’s opinion, believed there were elements in Semsar’s work that were Postmodern because they “…deconstruct the conventions of Modernism.…dismantling…the totality of meaning” and allowed a plurality not only of media but of approaches.[53]Tommy F. Awuy, a philosophy lecturer at Universitas Indonesia, “Hubungan Biennale dengan Postmodernisme”, The relationship between the Biennale and Postmodernism, harian Media Indonesia, … Continue reading Agung Hujanikajennong, in his graduation thesis for ITB, concluded that recognition of multiple meanings in a work of art beyond the artist’s statement was the defining Postmodern characteristic of the Ninth Jakarta Biennale. Plurality of interpretation appealed to those in opposition to the monoculture of Suharto’s regime and contributed to providing an intellectual space that later would accept political and cultural decentralization after the fall of Suharto’s regime. Legislation for Otonimi Daerah, or regional autonomy, for all its problems, was to recognize cultural difference and ethnic variations across the archipelago.

After 1995 the Postmodern debates decreased and few have revisited the arguments. Agung Hujanikajennong considers no real value for Indonesian art discourse emerged from the Ninth Jakarta Biennale and that its contribution was ‘confusion, if not disarray’. He considers the debate concerning Postmodernism was trivialized by being conducted in the daily newspapers, which was exemplified by their acronym, Posmo.[54]Hujatnikajennong, A., 2001 ibid. Outside Indonesia some theorists have proposed that if Postmodernism is recognized at all, it should be seen as the transition from the modern to the contemporary.[55]Postmodernism, according to Terry Smith, was a transitional development and even an anachronism, see Smith, T., 2009, What is Contemporary Art? ibid, p. 242 Although unresolved and contentious, the Biennale provided a platform to debate issues emanating from the international art world and acknowledged that a major change had occurred in the visual arts in Indonesia.

In 1995 Supangkat curated another important exhibition in Jakarta, the Contemporary Art of the Non-aligned Countries. Prior to Suharto’s Orde Baru, President Sukarno had been instrumental in establishing the non-aligned movement for member countries wishing to avoid sides in the Cold War. Their first meeting had been held in Bandung in 1955 and now, forty years later, Suharto was chair of the non-aligned movement and supported an exhibition to mark the event. Supangkat’s subsequent attempts to found a national gallery in the space used for the exhibition met endless difficulties, as we have seen.[56]The establishment of the Galeri Nasional is discussed in Chapter 2

The Global Curator

In 1989 Supangkat had attended ARX in Perth as an artist, but within a year he was leaving art practice behind for the role of curator. In 1990, although he was unable to attend due to his commitments at Tempo, he had been invited to a seminar at the Venice Biennale where Homi K. Bhabha was the keynote speaker. The seminar was organized by Mary Jane Jacobs and Art International and the resulting contact with Jacobs crystallized his thinking, particularly concerning the changing role of an independent curator. Jacobs has had a singular career organizing exhibitions and public art projects outside the mainstream and was an independent curator herself at this time, although she had been associated with major institutions in Chicago and Los Angeles through the 1980s. Supangkat considers that she was his mentor and credits her as the inspiration to become an independent curator himself.[57]The seminar was associated with Expanding Internationalism, A Conference on International Exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1990. Homi Bhabha’s keynote speech was titled Simultaneous … Continue reading

While most Indonesian curators at the time were focused on the commercial gallery exhibitions, Supangkat’s activities since graduation indicated his interest in theory and history. When asked why he had moved into art writing, he said:

“I became aware in the beginning that it was impossible to judge a work of art without knowing the discourse behind it.”

Few in the Indonesian art world had any understanding or experience of developments in the international forum, “… so I decided to fill the job, somebody had to do it,” he said. He ceased practicing as an artist for ethical reasons, to avoid bias in his judgment of the work of others:

“I wanted to be more open in relation to other people’s work….if I continued I would keep to my own position and judge other work from that particular belief.”[58]Supangkat interview, Jakarta, 2/07/2000

In 1992 the Japan Foundation invited Supangkat to participate in their exhibition, New Art from Southeast Asia. Although he interviewed, selected and introduced the artists to the Japanese curators, he was reluctant to define himself as a curator as he was so new to the role, so the Japan Foundation described him as a consultant. The Foundation then organized an intensive curatorial research program for him which involved visits to more than 20 museums across Japan. He met with directors and curators and found it exhausting but extremely valuable. It was also a special experience as the Japanese curator, Fumio Nanjo, commented that no Japanese curators had been given similar opportunities.

In the same year planning was underway for the first Asia-Pacific Triennial at the Queensland Art Gallery which was to be Supangkat’s first major international project as a curator. Supangkat and Sanento Yuliman were to work together but Yuliman unexpectedly and unfortunately died, leaving Supangkat as the central figure to present Indonesian art in the exhibition. According to Professor David Williams, who was on the selection team for APT/1, Supangkat was a ‘key person’ in the process of selection and he wrote the catalogue entries for all the nine Indonesian artists.[59]Interview, Professor David Williams, ANU School of Art, Canberra, 06/02/04. Williams was also involved with the subsequent APTs in the 1990s. Supangkat was then involved in APT/2 in 1996 and APT/3 in 1999 in various capacities from commissioner to member of the regional curatorial team and speaker at the associated conferences. He considers that the international art survey exhibitions of Australian and Japanese institutions were pivotal in the development of Indonesian contemporary art.

“[They] started us thinking, here in Indonesia, who are we? It’s the first time we encountered the so-called art world and started to understand art discourse. It is from that I developed the tools to debate Indonesian art.”[60]Supangkat interview, Bandung, 24/04/2005

Supangkat was the starting point for all international selection teams visiting Indonesia throughout the 1990s and his assistance is regularly acknowledged.[61]Among numerous examples, note: Apinan Poshyananda in Poshyananda, A. and Asia Society Galleries 1996, Contemporary art in Asia : traditions, tensions, New York, Asia Society Galleries, Harry N. … Continue reading He attended the exhibitions, wrote the catalogue essays and presented papers at conferences, seminars and symposiums. He has a presence in these forums and his education and writing experience, combined with his ability to communicate in English and his increasing familiarity with Western institutional systems, gave him more than a head start on any other Indonesian curator seeking a similar international profile. Once again, the lack of public infrastructure and curatorial training contributed to Supangkat’s lone status and it was not until the late 1990s that other curators began developing careers with contacts outside Indonesia. Since he was the main contact in Indonesia, it was the artists that he recommended that tended to be selected for international exhibitions – and then repeatedly selected.

A sample of the major international survey exhibitions in the 1990s with which Supangkat was involved includes: the Havana Biennale, Cuba, the international Cheju Biennale, South Korea, Sao Paolo Biennale, Brazil, Tradition/Tensions: Contemporary Asian Art, New York, USA, the Singapore Biennial, the Asian Art Triennial at the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum and many other projects originating from Japan. Among the awards Supangkat has received are the Republic Indonesia Award for Art and Culture in 2002 and the Prins Claus Award (Netherlands) ‘for posting cultural development in the Third World to the International world’.

Supangkat, as his C.V. indicated, considered he was a self-taught art historian, but he now became the historian and theoretician for Indonesian art in international forums, replacing the Western writers who previously spoke on behalf of Indonesian modern and contemporary art. No other Indonesian art writer at the time was wrestling with the concepts of Modernism to such a degree and the international gatherings to which he was invited provided a platform for the theories he was developing. His essays enter the center/periphery debates of Post colonial theory that were so heated at the time and laid claim to a ‘multimodernism’ which contradicted the theory of one originating Modernism emanating from Europe and America. The titles of his essays indicate the progression: from “Indonesia Report, A different Modern Art” in 1993, and “The Emergence of Indonesian Modernism and its Background” in 1995 to his own publication in 1997 Indonesian Modern Art and Beyond.[62]The essays and book as listed in the Bibliography are: Supangkat, J., 1993, “Indonesia Report, A different Modern Art”, Art and AsiaPacific, (Issue September 1993, inaugural edition, … Continue reading

Although Euro-American Modernism included politically activist art work, Supangkat considers Indonesian Modernism is distinguished by being apolitical and formalist. The return to socio/political commentary using experimental media and installations, he argues, marks the end of modern art and stands in opposition to it. This art he now terms ‘contemporary’ rather than Postmodern. Overall the definition of Indonesian Modernism begun by Sanento Yuliman and Supangkat is a work in progress which now needs a forum of debate to hone its essentials.

Connections of power and influence now developed that effectively became an alternative arts network outside the official government structures and bureaucracy. Supangkat and Cemeti were the most frequently contacted for advice, for example, an artist seeking information about residencies and scholarships will say, ‘I’ll ask Mella’. Supangkat has regularly worked with Mella and Nindityo since Mella’s student days and Mella reported,

“We have a good relationship with Jim, whenever we work together it seems to go well.”[63]Mella Jaarsma, interview, Canberra, 9/8/03

He curated the Indonesian / Dutch exhibition, Orientation in 1995 to mark the 50 years of Indonesian independence, an exhibition that had been initiated by Mella and included Nindityo. Supangkat uses the Cemeti’s files for research on artists when in Yogyakarta as Nindityo reported:

“… he’s very theoretical, although he also really needs the gallery files. I usually give them all to him.”[64]Wicaksono, Adi, 2003, “Wawancara dengan Nindityo Adipurnomo dan Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti Dominan karena Sendirian”, Interview with Nindityo Adipurnomo and Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti Dominant … Continue reading

Supangkat has tended to direct selectors to the same artists. He has been involved in the repeated selection of Nindityo for international exhibitions, including APT/2, Traditions and Tensions and Fukuoka.[65]See Appendix: Indonesian Participation in Global Exhibitions. In 2002, when Supangkat was invited to be on the selection committee for the second Fukuoka Triennial, Nindityo was the only Indonesian artist chosen. In reply to the suggestion of bias, Supangkat stated he was not responsible for culling the Indonesian artists on that occasion. He believed Nindityo was selected because his proposal was the only one that complied with the theme of the exhibition.[66]Telephone interview, Bandung, 20/05/02

Heri Dono is also part of this network, having been at art school with Nindityo and closely associated with Cemeti in the early years. Heri’s career was established before Jim Supangkat became an international curator, but from there on their paths converged. Supangkat selected and worked with Heri in a number of international exhibitions, eventually choosing him for one of the few exhibitions held at the CP Foundation space when it was in Washington D.C.[67]Heri Dono and Jim Supangkat worked together in the Sao Paulo Bienal, 1996, APT/1, Traditions and Tensions and the Sydney Biennale, 1996 amongst other exhibitions. The CP Foundation has continued to … Continue reading

Supangkat’s career, both local and international, has been remarkable. He recognized the changes in world art, the global nature of curatorial practices and the growing receptivity to contemporary Asian art, and he seized the opportunity it presented. International selectors needed an Indonesian contact and he had the ability to package Indonesian art to meet their requirements with the artists and presentations the global exhibitions preferred. As he said, ‘somebody had to do it’. At home he continually worked for the recognition of contemporary art and sought improvements for education and infrastructure through both government and private sponsorship.

The inherent problem with Supangkat’s position of power in the Indonesian art world is, like that ascribed to Cemeti, one of being ‘dominan karena sendirian’, dominant because he was alone. When power and influence reside almost entirely in one individual, it is their preferences, their personal and historical background, their education and perceptions that direct the visual art culture of the time. Eventually, being dominant and alone, that one individual can also become the focus of resentment and opposition. Instead what was needed was debate, a discourse amongst like-minded art theorists and this may yet develop, although as is continually noted, it has been delayed by the lack of infrastructure or training in the visual arts.[68]Postscript: revisiting these issues in 2012, the author notes the challenges to Supangkat’s theoretical arguments, especially those surrounding the Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX, by Agung … Continue reading

References

| ↑1 | Australian National University, Art History, Curatorship and Museums, http://info.anu.edu.au/StudyAt/_Arts/Undergraduate/Plans/_ARTSMARTC.asp accessed 09/04/07 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Wolff, J., 1981, The Social Production of Art, Macmillan Education, p.118 |

| ↑3 | Sylvester, D., “Curator and Critic London,” Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday November 20, 1999 |

| ↑4 | Interview, Agung Kuniawan, Yogyakarta, 3/6/02 |

| ↑5 | Patrick D. Flores, 2006, Past Periphery: Curation in Southeast Asia, unpublished research paper and excerpt from a manuscript for his book, Past Peripheral: Curation In Southeast Asia, Singapore, 2008 |

| ↑6 | See Rizki A Zaelani, “Hipotesis Kurator[-ial]” (Curatorial Hypothesis), and other essays on the subject in, ‘Focus’, Visual Arts, Vol. 10, December 2005 – January 2006, pp. 34-48 |

| ↑7 | Statement for the Goethe-Institut workshop, The Multi-Faceted Curator, 2006, http://www.goethe.de/ins/id/prj/mfc/cur/eff/enindex.htm accessed 10/08/2006 |

| ↑8 | Supriyanto, E., 2003, “Infrastruktur dan Proses Rezimentasi Seni – Wawancara dengan Enin Supriyanto”, Infrastructure and the Art Regime – Interview with Enin Supriyanto, in Yayasan Seni Cemeti, 2003, Aspek-aspek Seni Visual Indonesia, Yogyakarta, Yayasan Seni Cemeti, pp.151 -164 |

| ↑9 | In 2001 Jim Supangkat, with the Indonesian/Chinese entrepreneur, Djie Tjianan, established the CP or Center Point Foundation. Supangkat became the director of a CP Artspace in Jakarta and briefly in Washington DC, and curator of two CP biennales in 2003 and 2005. These will be discussed in more detail in a later chapter |

| ↑10 | Putu Fajar and Arcana Dahono Fitrianto, “Jalan Pintas Kurator Indonesia”, Indonesian Curatorial shortcuts, Kompas, Minggu 19 Maret, 2006, documents provided in pdf format at http://www.goethe.de/ins/id/prj/mfc/inf/enindex.htm accessed 02/08/06. Most members of the art community know of or are familiar with those practising as curators and opinions are often expressed in private conversations. Where possible these conversations are sourced and dated and /or cross referenced, that is, if more than one person expressed a similar opinion, it seemed reasonable to take it into consideration in describing a situation or making an argument. The entertaining ‘Omi’ blog: http://us.geocities.com/omimachi2/art3.htm accessed 14/05/06, also provided a survey of curators. |

| ↑11 | Marianto, Dwi M., 1995, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, PhD thesis; unpublished, University of Wollongong, pp.130 – 136 |

| ↑12 | This was reported by Setianingsih Purnomo, who obtained a Master of Arts (Hons.) from the University of Western Sydney, Art History department, 1995 and worked with the now defunct museum of the Universitas Pelita Harapan; conversation, 22/04/05; and Dwi Marianto, PhD University of Wollongong, 1995, Head of Research, ISI, conversation, 28/05/2002 |

| ↑13 | Asmudjo Jono Irianto, 2001, “Tradition and Socio-Political Context in Contemporary Yogyakartan Art of the 1990s”, in Outlet, Yogyakarta within the Contemporary Indonesian Art Scene, the Cemeti Foundation, Yogyakarta, p. 69 |

| ↑14 | Saut Situmorang, “WANTED: Indonesian Art Critic(ism)”, in Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, 1988-2003, Yogyakarta, Cemeti Art House, p.188 |

| ↑15 | Interview, Enin Supriyanto, 2009 |

| ↑16 | The Multi-Faceted Curator, 2006, ibid, ‘Observers’ |

| ↑17 | Hendro Wiyanto, personal communication, 13/5/02 |

| ↑18 | See Galeri Nadi website: http://www.nadigallery.com/previous_exhibition.htm accessed 09/04/07 |

| ↑19 | Jim Supangkat, interview, Bandung, 24/04/2005 |

| ↑20 | Putu Fajar and Arcana Dahono Fitrianto, 2006, ibid |

| ↑21 | Interview, Jim Supangkat, Jakarta 02/07/2000. He reported that there are two universities, both in the Philippines offering art history and he believed there was one course offered in India. See also “A Critic’s View”, Asian Art News, September/October 1997, p.47 |

| ↑22 | Informasi Kontributor, contributor information, Visual Arts, Oktober/Nopember, 2004, p.111 |

| ↑23 | Supangkat, J., 1994 The Critic At large, Asian Art News, 4 (issue no 2), p.15 |

| ↑24 | Rifky Effendy, “A General View on Today’s Art Infrastructure”, Visual Arts 6, April/May, 2005, p.22, quoted in Patrick Flores, ibid, p.84 |

| ↑25 | Kelola was established in 1999 in Solo and is now Jakarta-based. Website: http://www.kelolaarts.or.id/maganginternasional-e.php accessed 08/08/06, and http://www.kelola.or.id/ accessed 11/03/2012 |

| ↑26 | Rifky Effendy‘s Curriculum Vitae on the Goethe Institut website http://www.goethe.de/cgi-bin/goethe-print/print-url.pl?url=http://www.goethe.de/ins/id/prj/mfc/cur/eff/enindex_pr.htm accessed 10/08/2006 and the International Studio and Curatorial Program (ISCP) website, http://www.iscp-nyc.org/f_alumni.html. His blog: http://contempartnow.wordpress.com/ is last dated 2008. The Bandung Art Event, launched in 2001, was an attempt to raise the profile of Bandung artists but although considered successful locally, it was discontinued due to lack of funds. Other examples of residencies for Indonsian curators in Australia include: Agung Hujatnikajennong, who, on his Asialink residency in 2002/3, developed contacts with the Australian National University and the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, and worked with the Drawing Biennale at the Drill Hall gallery. Rain Rosidi, a lecturer at ISI and the manager/curator of now defunct Galeri Gelaran Budaya in Yogyakarta, had an internship in 2003/4 at the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery 4A, the Asia-Australian Arts Centre in Sydney. Heru Hikayat, briefly a lecturer at STSI in Bandung, and an independent writer/curator, had a residency with Artspace Sydney, Australia, also in 2003/4. |

| ↑27 | Conversation, Carla Bianpoen, Jakarta, 22/04/05. These figures would have applied at that time |

| ↑28 | These opinions were expressed in conversations with Rifki Effendy, Bandung, 06/07/00, Aminudin Th. Siregar, known as Ucok, Canberra, 12/08/2011 and as previously mentioned, an interview with Jim Supangkat, Bandung, 24/04/2005 |

| ↑29 | Interview, Amir Sidharta, Jakarta, 25/06/01. Some years later Sidharta refuted this statement, 20/05/20, stating that the Lippo collection is still intact in the museum’s collection and the auction house was not created for the purpose of liquidating it. |

| ↑30 | Asian Art News, 2006, “New Player on the Block”, Asian Art news, pp. 84 – 85 |

| ↑31 | Again I have relied on word-of-mouth. In 2001 when interviewing Amir Sidharta, 25/06/01, Jakarta, I asked him to list who, in his opinion, were the significant curators of contemporary art in Indonesia. In 2005 I re-interviewed Rizki Zaelani, 27/04/05, Bandung, and asked him the same. Both selected the same nine curators, Rizki’s list also including some further seven emerging young curators. The previously mentioned independent blog, http://us.geocities.com/omimachi2/art3.htm listed the same curators, although omitted the older generation |

| ↑32 | Carla Bianpoen, “The multi-faceted curator in question”, The Jakarta Post, April 10, 2006 |

| ↑33 | Farah Wardani graduated from Trisaki University in 1998 and gained a Masters in the History of Art from Goldsmiths College, London 2001. She taught theory at Universitas Paramadina, Jakarta, and has published art criticism in Kompas and The Jakarta Post, as well as editing the journal, Karbon. She has curated for Cemeti Art House, Edwin’s gallery, Nadi and ruangrupa. Wulan Dirgantoro graduated from ITB as an artist and subsequently gained her Masters in curatorial practice from the School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology at the University of Melbourne. In 2007 she took up a position in the School of Asian Languages and Studies, University of Tasmania, at the same time working as a freelance curator and writer with an interest in gender issues and crafts. She is presently undertaking her PhD in Indonesian Feminism and women’s art. Inda Citraninda Noerhadi graduated in archaeology from Universitas Indonesia, (UI) in 1983 and then undertook museum studies in Pittsburgh, USA, graduating with a Masters in Art History. She has practiced as a curator and as an artist, her own work and the exhibitions held at Cemara 6 indicating an involvement with mainstream Modernist art, except for her on-going commitment to the work of women and her involvement in a protest exhibition the gallery. |

| ↑34 | Carla Bianpoen, “Indonesian Women Artists, Between Vision and Formation”, in Oey-Gardiner, M., and Carla Bianpoen, eds., 2000, Indonesian women : the journey continues, Canberra, Australian National University, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, p. 68 |

| ↑35 | M. Dwi Marianto, 2000, “Recognising new pillars in the Indonesian Art World”, Text and Subtext, Exhibition Catalogue, Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore, p.145 |

| ↑36 | Wiyanto, H., 2000, Night sCream, Group Exhibition. The artists involved were Lenny Ratnasari, Anita Bilaningsih, Laksmi Shitaresmi, Regina Bimadona and Sekar Jatiningrum, Galeri Embun, 28 Jan – 15 Feb. 2000 |

| ↑37 | This was raised in the panel discussion that included Wulan Dirgantoro and Heidi Arbuckle, titled, ‘Gender, sexuality and artistic expression’, in the Indonesia Culture Workshop: Arts, Culture and Political and Social Change since Suharto, School of Asian Languages & Studies, University of Tasmania, Launceston 16 -18 December, 2005 |

| ↑38 | Low, M., C. Turner, et al., 2000, Beyond the future : papers from the Conference of the third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Brisbane, 10-12 September, 1999, Brisbane, Qld., Australia, Queensland Art Gallery, p. 137 |

| ↑39 | Bianpoen, who has greatly assisted my research, declined to be quoted on any opinion but for this one. Interview, Jakarta, 14/05/02 |

| ↑40 | The details of his personal history were provided by Jim Supangkat in interviews in Jakarta, 02/07/00 and Bandung, 24/04/2005. Note the discussion concerning the position of ethnically Chinese Indonesians and their role in the visual arts in Chapter 2, a position that the Supangkat family may well illustrate. The Supangkat family was subject to the strictures on ethnically Chinese under the Suharto regime to change their family name, yet in a privileged position, they prospered. They had access to education including aboard, were involved in the arts and emulated the Dutch and Western strata of society that collected artworks. |

| ↑41 | Supangkat, J. ed., 1979. Gerakan seni rupa baru Indonesia : kumpulan karangan. Jakarta, Gramedia, his own essay was titled, “Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru”. All translations used from this publication are by Mien Joebhaar, Jakarta, 2001 |

| ↑42 | The Indonesian artists at ARX 1989 were Supangkat, Riyanto, Sri Mallela and Nuarta. A full description is provided in Miklouho-Maklai, 1991, ibid, pp.107-108. The significance of ARX projects is discussed in full in Zeplin, P., 2005, “The ARX experiment, Perth, 1987-1999: communities, controversy & regionality”, Annual ACUADS Conference: artists, designers and creative communities, School of Contemporary Arts, Edith Cowan University, Perth |

| ↑43 | According to his C.V., Jim Supangkat was at different times during this period: the desk editor for art and architecture, international affairs, science and technology and health and behaviour, ending with the position of managing editor. |

| ↑44 | See the history of Tempo in Steele, J. E., 2005, Wars within : the story of Tempo, an independent magazine in Soeharto’s Indonesia, Jakarta, Singapore, Equinox Pub., Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. |

| ↑45 | Interview, Jim Supangkat, Bandung, 24/4/05. Galeri Lontar and Komunitas Utan Kayu was discussed in more detail in Chapter 2. |

| ↑46 | Dr Ariel Heryanto, academic and lecturer from Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana, Christian University Faithful to the Word, Salatiga, Indonesia, until 1996, a university with a reputation for producing intellectuals and activists. Presently he lectures in the Asian School, University of Melbourne, Australia, and is a writer on Indonesian and Asian cultural politics. Note: Heryanto, A., 1995 “What Does Post-Modernism Do in Contemporary Indonesia?” Sojourn Vol. 10 (No. 1), pp. 33-44 |

| ↑47 | Supangkat, J., 1993, “Seni Rupa Era ’80”, in Pengantar untuk Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX, Visual Art in the 80s: Guide to the Ninth Jakarta Art Biennale, (Jakarta Arts Council?). |

| ↑48 | Hujatnikajennong, A., 2001, Perdebatan Posmodernisme dan Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX (1993-1994), The Debate of Postmodernism and the 9th Jakarta Biennale (1993-1994), unpublished thesis, Fakultas Seni Rupa dan Desain ITB, Skripsi Program Sarjana. |

| ↑49 | FX Harsono, “Biennale IX Seni Rupa Jakarta, Dominasi Baru Pascamodern”, harian Kompas, 16 Januari 1994, quoted in Hujatnikajennong, A., 2001 ibid. |

| ↑50 | Semsar’s article, “Dengan tegas Menolak Postmodernisme dalam Seni Rupa”, Media Indonesia, 2 January, 1994, in Asmudjo Jono Irianto, Outlet, ibid, p.68, footnote. |

| ↑51 | Semsar Siahaan dikutip H. Sujiwo Tejo, dalam H. Sujiwo Tejo, “Semsar, Pelukis Penggali Kubur”, harian Kompas, 11 Januari 1994, quoted in Hujatnikajennong, A. 2001, ibid. |

| ↑52 | Hardi, “Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX: Sebuah Cangkokan Barat yang Mentah”, jurnal Horison 02/XXVIII, 1994, quoted in Agung Hujanikajennong, ibid, Chapter 4 |

| ↑53 | Tommy F. Awuy, a philosophy lecturer at Universitas Indonesia, “Hubungan Biennale dengan Postmodernisme”, The relationship between the Biennale and Postmodernism, harian Media Indonesia, 11/01/1994, in Hujanikajennong, A., 2001 ibid. |

| ↑54 | Hujatnikajennong, A., 2001 ibid. |

| ↑55 | Postmodernism, according to Terry Smith, was a transitional development and even an anachronism, see Smith, T., 2009, What is Contemporary Art? ibid, p. 242 |

| ↑56 | The establishment of the Galeri Nasional is discussed in Chapter 2 |

| ↑57 | The seminar was associated with Expanding Internationalism, A Conference on International Exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1990. Homi Bhabha’s keynote speech was titled Simultaneous Translation: Modernity and the Inter-National. Jim Supangkat, Email, 22/10/2010 |

| ↑58 | Supangkat interview, Jakarta, 2/07/2000 |

| ↑59 | Interview, Professor David Williams, ANU School of Art, Canberra, 06/02/04. Williams was also involved with the subsequent APTs in the 1990s. |

| ↑60 | Supangkat interview, Bandung, 24/04/2005 |

| ↑61 | Among numerous examples, note: Apinan Poshyananda in Poshyananda, A. and Asia Society Galleries 1996, Contemporary art in Asia : traditions, tensions, New York, Asia Society Galleries, Harry N. Abrams, p. 17, and Junichi Shioda in Junichi, S., 1997, Art in Southeast Asia Glimpses into the Future, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo and Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, p.153 |

| ↑62 | The essays and book as listed in the Bibliography are: Supangkat, J., 1993, “Indonesia Report, A different Modern Art”, Art and AsiaPacific, (Issue September 1993, inaugural edition, sample not for sale), pp. 20 – 24; 1995, “The Emergence of Indonesian Modernism and its Background”, in Asian Modernism: Diverse Development in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, Tokyo, The Japan Foundation Asia Center for the travelling exhibition, Asian Modernism, in 1996; 1997, Indonesian modern art and beyond, Jakarta, Indonesia Fine Arts Foundation. |

| ↑63 | Mella Jaarsma, interview, Canberra, 9/8/03 |

| ↑64 | Wicaksono, Adi, 2003, “Wawancara dengan Nindityo Adipurnomo dan Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti Dominan karena Sendirian”, Interview with Nindityo Adipurnomo and Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti Dominant because it was alone, Yayasan Seni Cemeti, Aspek-Aspek Seni Visual Indonesia, Paradigma dan Pasar, Yayasan Seni Cemeti, Yogyakarta, p.198 |

| ↑65 | See Appendix: Indonesian Participation in Global Exhibitions. |

| ↑66 | Telephone interview, Bandung, 20/05/02 |

| ↑67 | Heri Dono and Jim Supangkat worked together in the Sao Paulo Bienal, 1996, APT/1, Traditions and Tensions and the Sydney Biennale, 1996 amongst other exhibitions. The CP Foundation has continued to promote Heri Dono’s work and organised Heri’s exhibition, Civilization Oddness, at the Walsh Gallery, Chicago, July – October, 2006, http://foundation.cp-artspace.com/ accessed 09/04/07 |

| ↑68 | Postscript: revisiting these issues in 2012, the author notes the challenges to Supangkat’s theoretical arguments, especially those surrounding the Biennale Seni Rupa Jakarta IX, by Agung Hujatnikajennong in his essay, “The Contemporary Turns: Indonesian Contemporary Art of the 1980s”, in Iola Lenzi, ed., 2011, Negotiating Home, History and Nation, Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia 1991-2011, Singapore Art Museum, pp.88-9 |