Cemeti Gallery, later Art House, operated as an alternative space and, rather than be governed by sales, they focused on exhibiting experimental, avant-garde work. Cemeti was the first point of contact for those interested or involved in Indonesian contemporary art.

The majority of the research for this chapter was written after Cemeti had celebrated 15 years since its foundation and it is all the more timely to consider its role as it is now celebrating 25 years.

“It would be hard to deny that Cemeti Art House (CAH) holds a central position in the Indonesian art world… “

as Asmudjo Jono Irianto wrote in an essay for the book Cemeti Art House, published in 2003 to celebrate fifteen years since the foundation of gallery[1]Asmudjo Jono Irianto, “Cemeti Art House in the Indonesian Artworld”, in Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, 1988-2003, Yogyakarta, Cemeti Art House, … Continue reading. Cemeti Gallery, later Art House, operated as an alternative space to all the other galleries and, rather than be governed by sales, they focused on exhibiting experimental, avant-garde work. Cemeti was central in the process of Indonesian art going global and was the first point of contact for those interested or involved in contemporary art, whether from overseas or local. The gallery is a particular focus of attention as it became a gatekeeper in the Indonesian art world, forging contacts with international institutions and assisting in the selection of Indonesian art compatible with contemporary trends overseas. In the details of its history can be seen how international concepts entered Indonesia, and in the personal history of its founders, how artists were transiting the globe.

Cemeti was established in 1988 by the artists, Dutch-born Mella Jaarsma and her husband, Nindityo Adipurnomo, with the intention of exhibiting their work and that of friends. Their experimental, contemporary art had no other outlet due to the lack of government infrastructure or support from existing commercial galleries. The gallery was modelled on a Western commercial version but from its beginning they aimed to do considerably more than either Western or Indonesian galleries by providing a space for contemporary art debate and documentation for artists. By the mid 1990s Cemeti was becoming influential but with few alternatives to this ‘alternative’ gallery, some considered the outlet they provided had become somewhat of a narrow gateway.[2]Wicaksono, A., 2003 “Wawancara dengan Nindityo Adipurnomo dan Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti Dominan karena Sendirian”, Interview with Nindityo Adipurnomo and Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti, Dominant … Continue reading

From Ruang to Rumah, from art space to art house

The name, Cemeti, was believed to be from the Sanskrit for the whip, or whipping up, because it is “… another word for stimulating or getting things moving in the Yogya art world,” according to Mella Jaarsma.[3]Unless otherwise stated, all quotations and opinions expressed by Mella Jaarsma and Nindityo Adipurnomo are the result of conversations and interviews conducted in Yogyakarta June 2000, July 2001 and … Continue reading It was also the original name of Taman Sari or ‘Water Castle’, the historic ruins visited by tourists in the area behind the Kraton, or Sultan’s palace and near to the site of their first gallery, so the name seemed fortuitous.

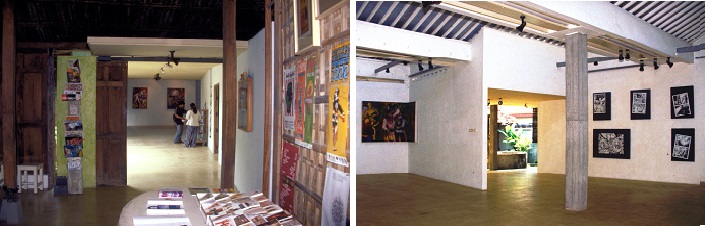

Cemeti began in the converted front room of their rented house in Jalan Ngadisuryan as a ruang seni rupa, or art space. Over a period of 11 years, from 1988 to 1999, 109 exhibitions were held in Jalan Ngadisuryan averaging 9 exhibitions a year.

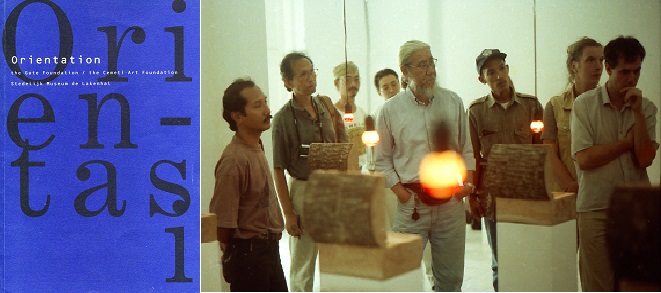

The next milestone in Cemeti’s history was the establishment of the Yayasan Seni Cemeti, or Cemeti Art Foundation, in April 1995 to manage the Orientation exhibition being mounted in conjunction with the Gate Foundation of the Netherlands. The Cemeti Foundation continued, functioning separately from the gallery as a resource centre for modern and contemporary art, and was, in effect, an alternative arts infrastructure. After ten years the support from HIVOS, the Humanist Institute for Development Co-operation funded from the Netherlands, was withdrawn in 2007 and, with a change in sponsorship, the foundation was renamed the Indonesian Visual Arts Archive, or IVAA.

In May 1999 the Cemeti gallery moved to a purpose-built exhibition space on Jalan D.I. Panjaitan designed by Eko Prawoto, an architect and friend, and was formally renamed Rumah Seni Cemeti, or Cemeti Art House.

Mella

The history of Cemeti is defined by the experiences of Mella and Nindityo. Mella was born in the Netherlands in 1960 and was a graduate of the Minerva Fine Art Academy in Groningen when she arrived in Indonesia. Minerva is a well-respected art college, the courses are five years and studio-based rather than academic for, in the Netherlands, art history and theory courses are offered at university level and Minerva is considered more of a technical college. Mella began her studies in the textile department but she considered the emphasis was too much on the medium when she was interested in concepts. She transfered to painting and eventually worked in a range of media including installation.

Mella joined her parents in Jakarta in 1984 as her father was involved in aeronautical engineering projects in Indonesia initiated by Vice President Habibie. At first she enrolled in the Institut Kesenian Jakarta, or IKJ, but as a graduate of a Western European art system, her concept of art and her practice fairly well established. It was unusual for graduate artists to enrol in Indonesian institutions but Mella had the promise of an Indonesian scholarship once there and an airfare paid by the Netherlands government on that basis. The scholarship was very small and in the long run never eventuated due to complications, but as it was for a government institution and IKJ was an art school funded by the city of Jakarta, Mella moved to ISI, or the Institut Seni Indonesia in Yogyakarta.

While at IKJ Mella came in contact with the new generation of Indonesian artists, in particular Jim Supangkat and FX Harsono, both of whom were lecturing there. Mella found herself the subject of endless curiosity as she was a novelty, so Jim Supangkat gave her the loan of his office as a space in which to work free from interruptions. Both Supangkat and Harsono, having been part of Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, (GSRB) were interested in art that sought alternatives to popular painting, and they recognised a different approach in her work from the modern art that dominated the Indonesian art scene in the 1980s. Harsono, remembering their first encounter in his catalogue essay for Mella’s exhibition, Think it or not in 1997, wrote:

“I have known Mella Jaarsma since 1984 while at the Jakarta Institute of Arts (IKJ), in Jakarta. In her exhibition in the IKJ I witnessed a unique trait which I had very seldom seen before amongst painters in Indonesia. There was a rational- analytical attitude in the background of her creative process. This attitude is often rejected by painters in Indonesia, for there is an opinion (who knows where it originated) that in the creation of a work of art, reason has no role at all, rather, feeling and emotions hold the important role in creation.”[4]FX Harsono, 1997, Mella Jaarsma, Think it or not, exhibition catalogue, Yogyakarta Cemeti Gallery, p.15. Quotations are given as printed in the catalogue and can reflect a somewhat stilted … Continue reading

Harsono, coming from the perspective of GSRB and the group’s interest in concepts and socio/political issues, was critical of art that was primarily the spontaneous expression of the artist. He saw in Mella’s work a practice based on balancing the subjective personal experience and objective social issues. Mella acknowledged that this was a product of her training and said:

“Yes, we understand that the human being is not only the brain, but also there are emotions, so we do not abandon emotions in creation. However, the finished works are not untouched by analysis…When I create a work there is always a basic idea, that I call a concept. If there is no basic idea, then the spontaneity will be undirected, spontaneity alone is not enough.”[5]Mella in conversation with FX Harsono, ibid., p.18

Both Supangkat and Harsono would become closely involved with Cemeti as it developed. Harsono gave a workshop in the early years of the Foundation and has exhibited with the gallery, especially during the politically tense time 1997 – 1998. Similarly Jim Supangkat was associated with Cemeti from its beginning and, as his career as an international curator and writer grew, a relationship developed based on mutual respect.

Mella enrolled in ISI in February 1985. Initially she knew little about modern Indonesian art, she said, but was attracted by the culture in Yogyakarta. She was working on a project involving shadows and photographing her own shadow which made her aware that shadows were a significant aspect of Indonesian life and culture. The sunlight, in comparison to the Netherlands, cast strong shadows during the day and at night both the lamps of the food stalls and the Wayang puppet plays communicate with shadows. After seeing cremation ceremonies in Toraja and in Bali, she perceived the shadow as a boundary between the material and non- material, but she chose not to use traditional Indonesian symbols in her own work. She explained:

“If I were to use symbols which I didn’t really understand, even though cognitively I could get to know them, they are not from my cultural background, and that is what one would call exotic.”[6]Ibid., p. 22

Mella was expressing a Postcolonial sensitivity concerning the appropriation of cultural signifiers, rejecting a Eurocentric view that framed another culture as exotic. Such ideas and attitudes had a growing currency in the international art world and would appeal to selectors for international exhibitions.

In 1998 Mella began a series of works concerning the cultural significance of body covering that would become the central concept of her oeuvre. Instead of appropriating recognized Indonesian cultural signifiers, she developed signifiers from her own perception of the culture, beginning with a jilbab, or body covering for Muslim women, made from frog skins. Mella’s work was selected for APT/3 in 1999 (the third Asia-Pacific Triennial, Queensland Art Gallery) where the concept was expanded into an installation of four cloaks made from the treated skins of fish, chicken, kangaroo and frogs and accompanied by photographs of the cloaks being worn. Some of the skins were from animals that are considered haram, or not permitted to Muslims: in this case, the frog meat and chickens’ feet were food only eaten by ethnically Chinese Indonesians.

The title of the work, Hi Inlander (hello native), referred to the derogatory term, inlander, used by the Dutch to denote indigenous Indonesians, but post colonially, it referenced racial attitudes between indigenous Indonesians and Indonesians of Chinese ethnicity. In the disintegration of the Suharto regime, riots broke out in 1998 that targeted Chinese Indonesians with appalling acts of rape, brutality and destruction of property. The art community was deeply affected by these events and Mella sought to create a work that would challenge Indonesians to consider the way they were perpetuating a colonial role in their attitude towards ethnic minorities. These jilbabs require the viewer to consider society from an alternative perspective, one different both in terms of gender and ethnicity, for to conceive of wearing frog skins and view the world from the inside of a constricting garment normally worn by women, is both physically and mentally disturbing for a male Muslim. When the frog skin jilbab was originally shown in the exhibition, Wearable, in 1998, Mella watched the reaction of an artist friend, a practicing Muslim, as he viewed the work. He said his first reaction was shock and anger but, when he read the artist’s statement, he said he started to think about the issues.[7]Interview, Mella Jaarsma, 28/06/00. The exhibition, Wearable Art, curated by Rifky Effendy and shown in Bandung, Yogyakarta and Ubud in 1999, exhibited a frog skin jilbab that was not full length. By … Continue reading

Through Cemeti Mella would gather Indonesian artists of like mind who were exploring cultural, and later political, issues in experimental art forms that did not have an outlet elsewhere. Cemeti would exhibit their work and facilitate their development through international contacts.

Nindityo

ISI had only just been formed from the original Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia, or ASRI in 1984 when Nindityo was in his final years as a student there. Born in 1961 in Semarang, Central Java, he was raised a Catholic and his artistic and philosophical interests were stimulated by his Catholic education.[8]Astri Wright, 1990 “Dancing towards Spirituality = Art”, in Nindityo Adipurnomo 1988 – 1990 Protection – Liberation – Expression, exhibition catalogue, p.3 His family had Priyayi, or aristocratic connections to the Sultan of Yogyakarta, although he states that no benefit accrued from this association and in fact he rejects it as outdated. The relationship, though, means that he is regarded as a “blue-blood” by other Javanese, despite his personal rejection of its importance. He speaks of a conflict between Western and Javanese values, a confrontation he found disturbing but fascinating, and these themes eventually formed the main body of his work.

At ISI in his role of lecturer’s assistant, he was responsible for foreign students and so met Mella. They exhibited together in the Karta Pustaka exhibition space associated with the Dutch Cultural Centre in Yogyakarta in May 1985, Mella making an installation with oil lamps and shadows and Nindityo exhibiting paintings and drawings. Mella extended her stay in Yogyakarta until March 1986 before returning to the Netherlands and by September of the same year Nindityo was able to join her in Amsterdam, Mella having assisted him in applying for a scholarship to the Rijksacademie.

The post graduate structure of the course at the Rijksacademie provided a studio space and daily contact with practising artists. He was surprised that in discussions with his tutor, Marlene Dumas, they would talk about Indonesian traditions such as the Wayang, not about formal aspects of his work, such as composition or colour which had formed the basis of his training at ISI. Nindityo’s first experience of European climate, culture and education came as a shock, as it does for most Indonesians, but it caused him to think about being Javanese in a Western context:

“I realised that a Javanese Catholic is different from Catholics elsewhere, because we have internalised the Javanese culture from childhood. We’ve gone through all the Javanese ceremonies – from the 7th month ceremony when the woman is pregnant, to the 7th day ceremony after birth; the feet touching the ground ceremony, the circumcision ceremony, and the 40th day mourning period after someone dies. So in addition to our faith in God and Jesus and Mary, the Javanese ceremonies become a deep part of us. This goes for mythology too…”[9]Astri Wright, 1990 catalogue essay, ibid., p.4

As had been experienced by A.D. Pirous and other Indonesian artists, Nindityo became more aware of his own cultural traditions when overseas. He found information concerning Javanese dance in a Dutch dissertation and, encouraged by Dutch friends, he experimented in performance.[10]Interview with Nindityo, Yogyakarta, 14/7/2001. The dissertation was by Clara Brakel and was titled, The Sacred Dances of the Kratons of Surakarta and Yogyakarta. See Enin Supriyanto, 1996 “The … Continue reading At the same time he was enthusiastic about the work of the CoBrA group, as well as Kandinsky, Klee, Miro and Chagall, so that on return to Indonesia his friends teased him that his work had become ‘too Dutch’.

Nindityo and Mella were married in the Netherlands and returned to Yogyakarta after a year as Nindityo felt he should complete his degree at ISI. At this time Nindityo was moving from painterly graphic work to art with content in a range of media and the disparity between the work required by the teachers and the work in which Nindityo and his friends explored their own ideas continued to widen.

In 1996 Nindityo was selected for both the Traditions and Tensions exhibition mounted by the Asia Society, New York, and Asia-Pacific Triennial/2 in the Queensland Art Gallery.

For APT/2 Nindityo exhibited Introversion (April the twenty-first), an installation of drawings and mirrors in carved wooden frames, suspended inside a curtained circle. The installation had at its centre the portrait of Kartini, a famous 19th century Javanese aristocrat honored for her support of women’s issues. The ‘April twenty-first’ referred to in the title is National Kartini Day when young girls are expected to wear to school a tight fitting traditional kebaya or Javanese blouse and a sarong.

Kartini provokes complex reactions concerning Javanese social structures and the position of women in Java today. She was a member of the aristocracy who, supported by Dutch friends, gained access to education, which was unusual for Indonesian women at that time. She advocated education and equal opportunities for women generally, was an artist herself, and resisted marriage, as she believed it would be the end of her already limited freedom. Yet eventually she could not escape family pressure and she entered a traditional polygamous marriage and died young, in childbirth.

Although Kartini’s significance as a feminist role model has been disputed by academics, her fame stems from her ideas for women recorded in her diaries and communicated in letters to Dutch friends. The debate concerns what form Kartini’s feminism took and the way in which the Suharto regime had subverted the protest inherent in Kartini’s personal life and writing, turning the subjugation of women into a festival for girls.[11]Saparinah Sadli, “Feminism in Indonesia in an International Context”, in Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, eds., Women in Indonesia, Gender, Equity and Development, Institute of … Continue reading She is honoured for her advocacy of women’s issues yet her experience exemplifies the powerlessness of women and their dependence on family.[12]Sylvia Tiwon, “Models and Maniacs, Articulating the Female in Indonesia”, in Laurie J. Sears, ed., Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, Duke University press, 1996, p.54

Like Mella, Nindityo developed a body of work based on the exploration of meaning in cultural signifiers, in particular the konde or elaborate hairpiece which is a symbol of status and seen in the framed drawing on the back of mirrors in this work. Nindityo is ambivalent about the konde, sometimes suggesting such traditions are stultifying and depicting himself as smothered by it, and a similar ambivalence surfaces in this work about Kartini. Although she is honoured in the centre of the work, she is isolated inside the claustrophobic circle of curtains.

Ruang Seni Rupa Cemeti

At the end of January 1988 the first exhibition was held in their house at Jalan Ngadisuryan in the new gallery, Ruang Seni Rupa Cemeti. The exhibition was a group show of five friends and ran for a month. Mikke Susanto described what this first Cemeti art space was like when he was a new student at ISI:

“… the exhibition space was, at most, around 4 metres by 14 metres. The remaining space was a passageway. The front room? Yes, that’s the gallery… There was no parking space for cars and bikes. At every exhibition opening, there were cars parked all over the road, often causing traffic jams. Bikes were just parked in someone else’s yard across the road. ….”

He described the appeal to the new generation:

“… the main attraction of that gallery was its unusual offerings. Most observers said that Cemeti had a special something, a different groove, the hottest works from Indonesia and from countries in the forefront of the visual arts, that it was “out on the edge”, not money-orientated, and that it was the most contemporary of all galleries.”[13]Mikke Susanto, “Pigura dan sejarah tersumbunyi”, The Frame and Hidden History, in Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years exploring vacuum, ibid, p.67

The sign said Cemeti was a modern art gallery with changing exhibitions: ‘modern’ in the sense of being ‘of this time’, and ‘changing exhibitions’ because they considered it important to have different activities each month and an exhibition plan for a year in advance. Their model was a Western European one but, with no experience of gallery structures or management and in an entirely different context in Indonesia, they developed their own system. They sought to distinguish themselves from the tourist art galleries common in Yogyakarta. Mella said,

“we wanted to make it clear to the public and the people passing by that we sold something different from what you would see in Malioboro street… to make it clear we were hanging exhibitions and not having art shows like in Bali for example.”

Nindityo defined their aims more formally in an interview given to Enin Supriyanto some eight years later:

“Our aim first and foremost was to work with artists to promote the ideas of progressive young artists. Secondly we wanted to provide an alternative infrastructure within the art world, which up to that time in Yogyakarta had been dominated by the senior and established artists. Thirdly, we wanted to sound out the possibilities for forms of management of a gallery in Indonesia, especially because in Yogyakarta there hadn’t been anything. There were only five practical exhibition places, using complicated procedures, and otherwise only art shops and antique shops.”[14]Enin Supriyanto, 1996, ibid, p.92

The first solo exhibition in the gallery in March, 1988, was held by Heri Dono and was followed by a series of solo exhibitions including that of Edith Bons from the Netherlands, in September. Thereafter nearly every year a Dutch artist would be shown in the gallery. Attendance at exhibition openings was between 70 to 150 people, usually students, artists, art critics, journalists and expatriates. After 1999 they would have up to 250 people in the new Cemeti gallery and these included diplomats, teachers from Gadjah Mada University, or UGM, and foreigners involved in cultural research. In the beginning there were no local collectors so foreign visitors to Yogyakarta contributed to the survival of the gallery and became part of their international networking.

For the first two years they did the invitations themselves, silk-screening three-colour designs that had been submitted by the exhibiting artist, and distributing posters around the city by bike. Technology, such as computers or photographic equipment, is expensive in Indonesia but living costs and domestic labour are cheap and there are servants who helped in the home with their two daughters. They had no telephone as few people in the early 1990s had a phone in Yogyakarta, and initially they had no help in running the gallery. In 2003, although there were two assistants in the office, Mella and Nindityo still carried responsibility for all the decisions. When a greater awareness of curatorial practice developed, Mella and Nindityo hoped that by employing a curator they would be relieved of some of the gallery work. Their expectations were, apparently, incompatible with those of the graduate from ITB that they eventually, and briefly, employed.

An early sale of 16 works by Heri Dono, Mella and others to an American architect caused them to think they should organise the exhibition space professionally, get a mailing address and change the name from ‘ruang’ to ‘galeri’. The gallery signs a contract with exhibiting artists although it would be almost impossible to enforce in Indonesia. The contract provides a ground for mutual understanding – for example, about the sale of works within a period before and after an exhibition. The gallery meets the cost of the invitations, the opening, posters, press releases, promotions and the transportation cost of artworks one-way from artists outside Yogyakarta.

Exhibiting artists determined the prices for their own work but there were marked discrepancies between prices achieved in Indonesia and those overseas once an artist had gained some international recognition. In the early 1990s works on paper sold for Rp. 90,000,[15]The rupiah was stronger then: according to Mella, in 1988 Rp90, 000 = AUD$60. In 2003 Rp90, 000 = AUD$16 but when Heri Dono returned from Switzerland, for example, he wanted Rp.2 million and they felt the Indonesian market would not support such a price.[16] Wicaksono, A., 2003 ibid, p.192 A 20% commission on sales, (later 30%), covered the cost of running the gallery, or did until the economic crisis in 1997. After the Knalpot exhibition in mid May 1999 that marked the opening of the new gallery, they didn’t sell anything for about 18 months, which gave them considerable cause for concern. Financially, as in other ways, their relationship to the gallery is complex. They have not been able to draw a salary, in fact the gallery has been dependent on their financial support at times, yet the gallery has also been a platform for their own work and the outlet through which they have developed their own careers. In this Cemeti is unusual for, according to Mella, an artist – run exhibition space in Europe that promotes the work of the owners along with that of other artists is not taken seriously. She said: “You are either a gallery owner full time or you are an artist”. Nindityo referred to their owner/artist/gallery relationship as a “mutual symbiosis”.[17]Ibid, p.192

Up to 1995 Mella and Nindityo concentrated on their own work, raising a family and exhibiting the work of their Indonesian friends and contacts, but thereafter international commitments made increasing demands. After the economic crisis and terrorist tensions affecting tourism, it was the development of international contacts that proved to be invaluable and protected them when sales were slow. These contacts included the Singapore Art Museum who has specialised in collecting Indonesian contemporary art and used Cemeti as a major source of work and advice.[18]Ibid., p.195 Mella herself was fortunate to have sold to the Singapore Museum before she negotiated the sale of a work to the Queensland Art Gallery, for Singapore had set a price benchmark at international levels rather than the normal Indonesian price range.

Rumah Seni Cemeti

In May 1999 they opened the new gallery, Rumah Seni Cemeti or Cemeti Art House on Jalan Panjaitan. It was purpose-built, financed in part by the sale of both Mella and Nindityo’s work to the Queensland Art Gallery, and reflects many of their artistic aims and ideas. The entry and first exhibition space is a traditional Javanese house which was purchased and moved to the site. It has a natural timber roof with wide overhanging eaves supported on columns and screens that, to the front, act as the entrance and to the rear, provide access to a small internal garden. The Javanese house is both an exhibition space and a meeting place with a table, seats and array of art publications. A covered corridor metaphorically connecting the old with the new, links the Javanese house with a larger, light and open exhibition space that is the ‘white cube’ of a modern art gallery.

Cemeti forged contacts with like-minded artists, with government bureaucracies and NGOs, and exercised its knowledge of international organisations to facilitate programs and gain residencies and sponsorships. In 2007 the Cemeti website listed three Dutch organizations along with the Kelola Foundation and the Ford Foundation as sponsors of their activities.[19]In May 2007 the Cemeti Art House website declared their supporters as Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development, Kelola – Yayasan untuk Seni Budaya, Artoteek den haag, Cultural & … Continue reading Foremost amongst the cultural institutions established by the Netherlands government in Indonesia is Erasmushuis in Jakarta with two related institutions, one in Surabaya and Karta Pustaka in Yogyakarta. Erasmushuis created what they call a ‘sounding board’ of advisors drawn from leading figures in the arts and related institutions, six in Indonesia and six in the Netherlands, Mella and Jim Supangkat being their Indonesian advisors.[20]www.erasmushuis.or.id see ‘Advisors’ accessed 02/09/03 Opportunities for scholarships, grants and sponsorship exist through these cultural links and being able to navigate cultural institutions in the Netherlands was an invaluable asset for Mella, Nindityo and Cemeti. As Cemeti‘s profile grew, organisations wished to be associated with its cultural activities. Mella stated that supporting visiting artists was an important part of the gallery’s policy as a centre for debate and the dissemination of information, so the Dutch embassy or the Japan Foundation provided sponsorship.

Such advantages contributed to their success and eventually it drew envy, some Bandung artists referring to them as the ‘Cemeti Mafia’ and saying that Yogyakarta generally dominated art events from which they had been excluded. Whether accurate or not, the limited opportunities and lack of alternatives in the small world of contemporary art contributed to this enmity.[21]These comments were made in a group discussion, Bandung, 04/07/2001, one local curator saying that Tisna Sanjaya would be the only Bandung artist to be exhibited at Cemeti. This was somewhat refuted … Continue reading

The Cemeti Foundation

The ancillary work of the gallery, documentation, dissemination of information and functioning as a centre for debate, proved to be demanding. In 1995 the organisation for the Orientation exhibition mounted in association with the Gate Foundation, an Amsterdam- based NGO, made it necessary for Mella and Nindityo to set up the Yayasan Seni Cemeti, Cemeti Art Foundation or CAF in order to manage the finances and administration of the exhibition. CAF became, in effect, an alternative arts infrastructure in the absence of any other public institutions. Its website profile declared:

“During its first eight years, CAF still aspired to function as a subsystem of art infrastructure in Indonesia by playing a role that hypothetically should be performed by most competent agent, which is the government.”[22]Cemeti Art Foundation is now the Indonesian Visual Art Archive and the website that recorded this comment no longer exists

In 2007 the Foundation underwent a transformation due to a change in sponsorship and it was renamed the Indonesian Visual Arts Archive, or IVAA.

Orientation Exhibition

The Orientation exhibition was organized to celebrate 50 years since the declaration of Indonesian Independence with an exhibition of five Dutch artists in Jakarta in 1995 and five Indonesian artists in Leiden in 1996. The Indonesian artists were Heri Dono, Anusapati, Andar Manik, Nindityo Adipurnomo and Yudhi Soerjoatmodjo, a photographer. The project was initiated by Mella and Esther de Charon de Saint Germain, who was undertaking an internship with the Gate Foundation. According to Jim Supangkat, the only Indonesian curator, the aim was to foster a debate about the differences between contemporary art in different parts of the world.[23]Jim Supangkat, 1995, “Knowing and understanding the differences’, in Orientation, catalogue, Gate Foundation, p.46

The Indonesian art aimed to challenge the assumption that modern art was the prerogative of the West and that Indonesian modern art was derivative. The ex-colonised was exhibiting Western – influenced work to the ex-coloniser, and in a somewhat patronising atmosphere where only one of six curators was Indonesian.[24]Carla Bianpoen, in her article for the Jakarta Post, 24 August, 1995, points out that although there were an equal number of artists participating from Indonesia and the Netherlands, the balance … Continue reading Nindityo, making a claim for a distinctive Indonesian modern art, said in an interview with Esther de Charon de Saint Germain:

“I have been told that I have become extremely Western in my work. I don’t know if that’s the case. It depends what your options and sources of inspiration are. Your work continues to have the identity of its country of origin.”[25]Esther de Charon de Saint Germain, Interview with Nindityo Adipurnomo, 1993, Orientation catalogue, 1995, ibid, pp 50-52

Anusapati felt that there had been no real theme to the exhibition, no time to interact with the Dutch artists beforehand and it had been hard to understand their work so, in the long run, “everyone did their own thing”.[26]Interview, Anusapati, Yogyakarta, 13/05/05

For example, the Dutch artist, Erzsebet Baerveldt, questioned the meaning carried by events and figures from European history in her work. Baerveldt not only explored, but she also identified with a 16th century Hungarian countess who had a reputation of being a vampire, legally changing her name to that of the countess and wearing a reproduction of her clothes. The title of her work, 69, was a reference to similarity yet difference, for while the numbers were similar they still represented different amounts.[27]Kim Knopprs, 2003, Morbus Sacer, (Holy Desease), exhibition catalogue, Netherlands, provided courtesy of Erzsebet Baerveldt and translated by Dieneke Carruthers

In comparison, Anusapati exhibited an installation titled Preserve Versus Exploit which referred to environmental issues. Nine wooden boxes on plinths contained the seeds of endangered species of trees and were individually lit and presented as if wood were sacred. Dwi Marianto, reviewing the exhibition when it was held in the Galeri Nasional in 1995, commented on the use of “old or conventional painting techniques” by the Dutch artists in a manner that appeared to challenge conventions of modern Dutch art.[28]M. Dwi Marianto, 1996 “Cultural Orientations, Art from the Netherlands and Indonesia”, Art AsiaPacific, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp.38-39 Each group was addressing their own cultural environment but from different standpoints: the Indonesian artists raised socio/political issues while the Dutch artists re-positioned themselves in relation to their past in a Postmodern manner, questioning received European histories.

The Foundation was initially housed in Jalan Ngadisuryan but moved to Jalan Patehan Tengah, Yogyakarta and has subsequently moved again.[29]The first two properties were rented, but as of 2011, the IVAA address is understood to be owned by the foundation and is listed on their website as: Jalan Ireda Gang Hiperkes MG I-188 A/B, Kampung … Continue reading HIVOS, The Humanist Institute for Development Co-operation, which is funded from the Netherlands Ministry of Development Co- operation, supported the Foundation, paying for the structure, such as rent, employees’ salaries and the collecting of resources, library books and catalogues.[30]www.hivos.nl accessed 28/05/03 They continued to do so for ten years, their normal time limit for programs of support, and in 2006 other sponsorship for CAF had to be found. Any special projects, such as the publication of books or the mounting of an exhibition, required the Foundation to seek sponsorship outside HIVOS. The Board of the Foundation consisted of Nindityo and Mella, Agung Kuniawan, his wife Yustina W. Nugraheni, who was treasurer, Anggi Minarni, Director of Karta Pustaka, and Raihul Fadjri, a journalist. There have been subsequent changes including the addition of Anusapati and an architect to the board. Its administrative structure is separate from the Cemeti Art House, and unless they are co-operating on a project, there is no direct financial support from the Foundation for the gallery, but until the name change, Cemeti was inevitably associated with the Foundation.

The Cemeti Foundation was a combination of arts council, library and research centre and provided a meeting place for those involved or in interested contemporary art. The Foundation conducts practical workshops and regular lectures by Indonesian and visiting artists, writers, critics and theorists. They hold a radio talk show, Dialog Seni Kita, Our Art Dialogue, broadcast on UNISI FM every Friday, and intermittently publish a magazine called Surat, or letter. They have inaugurated an Artist in Residence program and so far have hosted each year since 1999 artists from Lithuania, Singapore and Bangladesh, among others. They have developed a system for the documentation of reviews, essays, ephemera and written material, photographs and slides, constituting all available visual and written documentation on contemporary Indonesian artists and their exhibitions, an activity no other institution is undertaking. Their book publications are the first to explore contemporary Indonesian art debates in depth, their early publications including: Outlet, Yogyakarta within the Contemporary Art Scene in both Indonesian and English and the three-volume Aspek-Aspek Seni Visual Indonesia, in Indonesian. The three volumes of Aspek-Aspek cover Identitas dan Budaya Massa, Identity and Mass Culture, Paradigma dan Pasar, Paradigm and the Market and Politik dan Gender, Politics and Gender. The Foundation also mounted and administered AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia a significant exhibition that travelled from Asia to Europe between 1999 and 2000.[31]AWAS! and Cemeti’s involvement in political art is discussed in more detail in the chapter on Reformasi

CAF developed a program to promote visual art appreciation in secondary schools where little if any art is taught. They carried out a survey of 141 public and private schools in the central Yogyakarta region and found that less than 10% of the schools were providing visual arts education even as an extracurricular subject. Between 2001 and 2003 CAF organised artists to work with pupils, beginning with 30 students in the first year but growing to 100 students in the following years. A second project, the Gerilya, Guerrilla or G project, has targeted teachers. School teachers are overworked – 45 students being the usual class size – and underpaid, so, as with lecturers in the tertiary art academies, they often take extra work for sufficient income. The government provides a workshop/training program through the Pusat Pengembangan Guru Kesenian or Centre for the Professional Development of Art Teachers, but few had access to it and it was not considered effective. The G project was funded directly from CAF’s annual budget from HIVOS and is, therefore, threatened by the withdrawal of the latter’s support.[32]See:”An Overview on AsuRA & G-Project of Cemeti Art Foundation”, 2006. This report was provided by Aisyah Hilal, director of CAF at the time and a recipient of an Asialink /Kelola … Continue reading

Although the Cemeti gallery doesn’t benefit directly or financially from association with the Foundation, it benefits indirectly by influencing what the Foundation does and combining in projects such the travelling exhibition, AWAS! The more effective the Foundation was, the more it attracted sponsorship and grants from cultural organisations both inside and outside Indonesia. Perhaps most importantly, Cemeti appears as a central feature in all the aspects of the Foundation’s publications, the gallery’s position in the art world being discussed in Outlet and Aspek-Aspek Seni Visual Indonesia; and it is the artists most closely associated with Cemeti who are reviewed and documented. Intentionally or not, Cemeti is writing its own history in Indonesian contemporary art, another way of affirming a power base.

Artistic preferences

Cemeti was not only a role model for art practice and gallery management but a gatekeeper in the selection of exhibiting artists. Mella and Nindityo are often referred to as curators but the selection of work for exhibition, from both overseas and Indonesian artists, is based on Mella and Nindityo’s personal aesthetic taste and judgement rather than objective curatorial paradigms.[33]This opinion was expressed by Asmudjo Jono Irianto, 2001, “Tradition and the Socio-political Context in Contemporary Yogyakartan Art of the 1990s”, in Outlet, Yogyakarta within the … Continue reading Since most Indonesian curators have had no theoretical background or training and the majority have been practising artists, selection for exhibition is usually based on personal preference. When asked about her curatorial practice, Mella added that her selection was also based on an artist having a continuing commitment rather than only making work when invited to exhibit, as was common.

Their exploration of social and cultural issues through contemporary art practice inevitably involved the gallery in contentious and political exhibitions and events and it was this content and experimental media which appealed to international selectors. Nindityo said that if a foreign organisation needed young artists, Cemeti would provide names but the originating organisation made the selection. He said,

“… We are just facilitators, we really just deliver them, like a bridge. I really don’t prepare or design them.”[34]Wicaksono, A., 2003 ibid.

Yet the artists proffered were already judged noteworthy according to Cemeti’s criteria.

It is in this interlinking of different roles for the gallery and its owners that the problems arise because Mella and Nindityo have one role based on personal preference while the other curatorial role has a presumption of objectivity associated with it. Under other circumstances, as the gallery owners they are at liberty to select, show, promote and sell any work according to their personal taste. But as they became increasingly successful, with no other gallery offering any real competition or opposition, their selection became a sensitive issue. Cemeti was ‘Dominan karena sendirian‘, dominant because it was alone, to quote the title of the interview written by Adi Wicaksono.

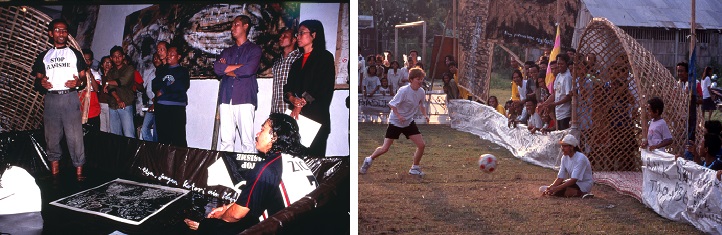

Certain exhibitions have appealed to them in particular. For Nintityo, the most significant exhibitions up to 2002 have been an experimental sound performance in September 1999 and Tisna Sanjaya’s Art and Soccer for Peace in 2000. Cemeti worked with Haryo Yose Suyoto, a musician and composer teaching in the music department at ISI. He created a performance with local labourers using the tools of their trade to produce percussive sound. The performance, titled Komunitas Bunyi, Noise Community, involved the labourers sitting in groups on the floor, chopping or hammering at their normal work in an orchestrated cacophony.

Tisna Sanjaya, a Bandung artist and the head of Printmaking at ITB, organised a series of events that brought soccer into the gallery and the gallery onto the soccer field. Ruang Etsa dan Sepak Bola, Etching Place and Football, also known as ‘Art and Soccer for Peace’, challenged the concept of an exhibition space and introduced the viewer to approach and participate in art in an entirely different way. Tisna washed the feet of the football players who had come to the gallery to register for the match, a gesture of ritual cleansing before prayer for Muslims. He then mounted artworks on woven bamboo around the football field and played football for a week, taking breaks to repair the drawings and paintings around the field. These works were an expression of experimental and community-based art that made reference to socially and politically sensitive issues in the tense environment post Reformasi.

Tisna holds an interesting, possibly unique, position in relation to his students and his community. His wit and playfulness appeal greatly to the young students who continually frequent his house, but he is also known for his commitment to his community and to Islam. A series of etchings on the wall of his home that are dark and dense with violent figures, relate to the riots in 1998. The works are mounted with jars of dirty water that came from washing the feet of his mother and other family members as a form of atonement for the victims of violence.[35]Interview, Tisna Sanjaya in his home, Bandung, 04/07/01

Certain art will not be seen in the Cemeti gallery: not surprisingly the work of the older generation mainstream artists to which Cemeti was the alternative, but also that of the Yogyakartan surrealists. A surreal style of painting became popular with students at ISI from the mid 1980s to the early 1990s, apparently as the result of a 3-month workshop in realist painting and Renaissance techniques given to lecturers at ASRI by the Dutch artist, Diane van den Berg, in 1982. She later assisted three artists to study in the Netherlands, including Sudarisman, who himself later lectured at ASRI.[36]Dwi Marianto, 1995, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, PhD thesis; unpublished, University of Wollongong, p.52 and p.163 Dwi Marianto argued in his PhD thesis that Yogyakartan surrealism was a psychological reaction to the repression of the Suharto regime. Enin Supriyanto prefers the description, ‘neo mysticism’ rather than surrealism, as none of the artists involved had any real understanding of the theory behind European Surrealism.[37]Interview Enin Supriyanto, 02/09/09. The term, ‘surrealism’ is more commonly used than ‘neo mysticism’ but due to debate concerning the relationship between Yogyakartan … Continue reading Artists such as Agus Kamal, Ivan Sagito, Sudarisman and Lucia Hartini have all developed careers based on a realistic/surreal style of painting and have prospered inside Indonesia but not internationally. Mella stated:

“I do not like surrealist art and I am not so fond of the work of Lucia Hartini. Surrealistic art is amazingly terrible. There are two works (by Hartini) I can appreciate: the one with the bricks and the eyes and another with a flying wok. Not our style, we wanted to show something else.”

Significantly few female artists or art that addresses women’s issues have been exhibited, even though Mella’s work is open to interpretation through gender. Since the gallery opened in 1988 they have had some 64 solo exhibitions of male artists but only 8 female artists.[38]Exhibition schedule at Cemeti Gallery 1988 – 2002 in Cemeti Art House 2003, 15 years exploring vacuum, ibid, pp. 244-247 Other galleries have a similar ratio or worse, which made female participation in the visual arts in Indonesia in the 1990s one of the lowest, if not the lowest, in Asia. Few writers, either Indonesian or international, have drawn attention to this disparity.[39]Galeri Lontar, in Jakarta, the only other gallery to maintain records at the time, indicated a similar low ratio of female to male artists in their exhibition list. Statistics have proved difficult … Continue reading

The Indonesian art world is dominated by male curators, collectors, gallery owners and bureaucrats who consider issues of gender are exclusively a problem for women. Women artists shy from the label, ‘feminist’ and resist Western Feminism’s emphasis on male dominance, often while using the female form symbolically in their work, as seen in the sculpture of Dolorosa Sinaga. Saparinah Sadli, chair of the Indonesian National Commission on Violence against Women, speaking at the Indonesian Update Conference at the Australian National University in 2001 said:

“The terms ‘feminism’, ‘feminist’ and even ‘gender’ are still questioned by the majority of Indonesians. They are considered by many to be non- indigenous concepts that are irrelevant to Indonesian values.”[40]Saparinah Sadli, “Feminism in Indonesia in an International Context”, Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, eds., 2002, Women in Indonesia, Gender, Equity and Development, Singapore, … Continue reading

Western feminist writers also have been slow to explore issues of gender in Asian, let alone Indonesian, art although there have been significant essays and recent exhibitions, such as Global Feminisms organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 2007, which included the Indonesian artist, Arahmaiani.[41]See Reilly, M. and Nochlin, L., eds, 2007, Global Feminisms, new directions in contemporary art, Merrell, London and New York and The Brooklyn Museum. Astri Wright was one of the few writers … Continue reading Asian feminisms and Asian gendered art is hedged by thorny issues concerning similarity and difference. Asian women artists may share similar histories of repression yet experience it differently, coming from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds. They may, as a result, prioritize other issues, such as access to education and economic equality over resistance to patriarchy.

The number of exhibitions in Cemeti for women artists is the tip of an iceberg. The issue of women in the visual arts is one aspect of the much larger, wide ranging issue of the role of women in Indonesia generally, roles which are complicated by traditional values overlaid by urban modernity and religious practice. In exploring the position of women it is necessary to move beyond the visual arts, crossing disciplines to history, sociology, law and religion, and, in the course of this book, it will be approached from more than one perspective.

Mella herself functions as an independent European artist and in early interviews seemed not to recognise the difficulties and limitations faced by Indonesian women artists in a male- dominated society, conditioned by social and religious customs to prioritise the needs of husband and family. Mella considered that since Indonesian female artists with children would have servants, the issue was only a matter of commitment to their career. Nindityo, when asked whether women needed assistance, repeated what many in Indonesia reply when asked about gender issues: “Women need help? Men need help too!” When asked why women don’t continue in artistic careers, he declared himself ‘mystified’.

Goenawan Mohamad, when approached on the subject, denied gender was an issue in Indonesia or that there was prejudice in the art world, but after some debate he demurred,

“the problem is not the curators. the problem is marriage. The social pressure is that women must get married and lose their career.”[42]Interview, Goenawan Mohamad, May 17th, 2002

Educated women may graduate in the visual arts and work as an artist or in a gallery, but although the number of women in the visual arts was rising, after graduation too many ‘disappear’.[43]Bianpoen, Carla, Wardani, Farah and Dirgantoro, Wulan, 2007, Indonesian Women Artists, The curtain opens, Jakarta, Yayasan Seni Rupa Indonesia, p.27 The primary role for women is understood to be within marriage and outside marriage a woman is considered an incomplete human being. Work and a career are not forbidden but must come second to a woman’s role in the family and contribute economically to the family rather than be for personal development. The discussion about women in the visual arts in Indonesia is in reality a debate about the position of women in a society structured on dominant, male Javanese and Islamic conventions.

Mella’s own work exploring sexuality and cultural taboos relates to the role of women and feminist theory although she is resistant to theory-driven work. She said,

“There are still many other taboos in society that should be questioned: sexual taboos and gender issues, religion. There are many things inside you to do with your culture and your background and it is important to make people aware.”

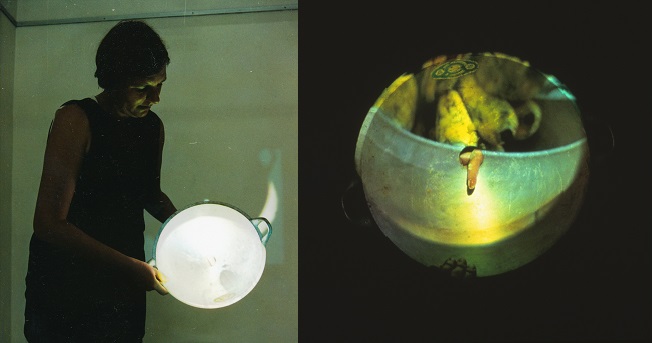

The main body of Mella’s work has related to body covering interconnected with constructions, shelter and projections in an exotic range of media that incite speculation and debate beyond simple clothing. The first of these works made at the height of social and political turmoil in 1998 during Reformasi, was the floor length jilbab or burka made from the skins of frogs that, although food for Chinese, are considered not permitted by Muslims. [44]The frogskin jilbab became one of four pieces shown by Mella Jaarsma in the Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1999 titled, Hi Inlander (hello native), and subsequently purchased by the Queensland Art Gallery. The full body covering referenced Islamic female dress and was open to a feminist interpretation, but Mella’s later and considerable body of work extends beyond issues of gender and require the viewer to contemplate diverse codes and cultures. The medium itself is indicative of the issues Mella is exploring, for example: buffalo leather, (Bolak Balik, 2000); cloth badges, (The Follower, 2002); tents, (Refugee Only, 2003); penis sheaths from Papua, (My name is Michaella Jarawiri, 2007); and zips, (Zipper Zone 2009). These works are often presented in the form of a performance and are portable in more than one sense, being worn in international exhibitions around the world.[45]See Mella’s website: Mella Jaarsma accessed 9/02/2012 and the catalogue of her exhibition, The Fitting Room, Galeri Nasional, Jakarta, 27 October – 8 November, Selasar Sunaryo Art Space, … Continue reading

An earlier work, a performance she gave in connection with the Yogyakarta Biennale in 2000 titled, Under Cover, involved ten woks, each with a banana sticking through a hole in its centre. Mella, in a dramatically lit performance, handled the projecting bananas in a manner that combined cooking, normally the role of women in the home, and sexuality. The local expatriates laughed at the piece but Indonesian viewers didn’t make any comment at all. Mella said, “It is difficult for a woman to express something about sexuality, it is more accepted that men make such works than women. Arahamiani is one but no one follows her approach”.

Arahmaiani, well known both inside Indonesia and internationally as a Feminist activist performance artist, has never had a solo exhibition at Cemeti, although a video of one of her performance works was included in the travelling exhibition, AWAS! Mella and Nindityo consider Arahmaiani’s approach too confrontational, an opinion they share with many in the Indonesian art world, especially women.

Cemeti has also not been an effective outlet for the growing youth culture in Indonesia, although they have attempted to be so on various occasions. This youth culture was the product of increased prosperity and education and in particular, globalised media, television, film, music and the Internet. In the first half of the 1990s youth culture was also politicised and involved in student activism critical of the corruption and lack of freedom under the Suharto regime.[46]Various writers describe the development of such influences, including Emmerson Donald K., 1999, Indonesia beyond Suharto : polity, economy, society, transition, Armonk, N.Y., M.E. Sharpe, pp.285 … Continue reading

While alternative art groups have only rarely exhibited in the gallery, Cemeti has hosted solo exhibitions of some of their members. Both group and solo exhibitions can be a challenge not only to mount, but to Cemeti‘s concept of art exhibition. A member of the alternative collaborative group, Apotik Komik, Bambang ‘Toko’ Witjaksono, held an exhibition titled Mas Makelar, or the Broker, in 2001 where he filled Cemeti’s exhibition space with traders of second-hand goods from the Alun-alun kidul, the square south of the Kraton, and their wares. Bambang’s nickname, ‘Toko’ or shop, indicates his ongoing interest in bargaining and the market. He put everything up for sale from his own work to the lavatory doors, and even jokingly, the gallery itself.

In 2003 ruangrupa, the Jakarta based group of young artists involved in new media and digital art, held a ‘happening’ and exhibition in Cemeti titled Lekker Eten Zonder Betalen, Tasty Meal Without Paying. They brought the communal process of eating a meal into the gallery and demanded that the remains constitute the exhibition. The invitation stated: “All happenings and recordings will be left behind/left in place as objects that have used or given energy throughout the exhibition.”[47]Exhibition invitation titled in Dutch, Lekker Eten Zonder Betalen, Tasty Meal Without Paying, 16 participants, March 2-30, 2003, Cemeti Art House, email, 26/02/03 As part of their work, the night before the opening they held a party that ended in total chaos, food on the wall, drunken participants and noise to disturb the neighbours and bring the police. Nindityo reported to Mella who was in Singapore on a residency at the time, “Now I am confused what to do because ruangrupa wants to leave the mess rotting in the space for the whole month, lots of rats and maggots will appear, and it will be smelly! Don’t be mad at me!”[48]Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years exploring vacuum, ibid, ‘Anecdotes’, p.7

Such an event, not unknown in Western conceptual practice, was an intentional challenge to what was considered appropriate action and display in the gallery. The anarchic experiments of youth and street culture were uncomfortable for Mella and Nindityo and possibly incompatible with their expectation of an exhibition in a fine art gallery. Cemeti‘s structure, with regular exhibitions, catalogues and stockroom, is based more directly on Western commercial art gallery practice aimed at buyers and collectors.

Christine Clark, project manager for the Asia-Pacific Triennial in the 1990s, recognised that alternative, artist-run spaces were a feature of the Asia-Pacific region and that in the absence of state-run arts institutions, “… the ‘alternative’ becomes mainstream”.[49]Christine Clark, “Distinctive Voices: Artist – initiated spaces and projects” in Turner, C., ed., 2005 Art and Social Change Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, Canberra, ACT, … Continue reading Clark included Cemeti among these alternative spaces but she acknowledged that Cemeti had become an established institution. The younger generation generally do not see Cemeti as a space for their activities and such youth groups are only tenuously associated with any regular exhibition space – they were the growing alternative to the Alternative.

Artistic preferences

In August 2003 Cemeti celebrated 15 years as an arts centre and exhibition space with a project entitled Exploring Vacuum that was in effect a form of self evaluation and a title that, like the name Cemeti itself, has provocative alternative meanings. On the one hand a vacuum is an empty space, implying that for lack of other places they created a space in which ideas can be explored. On the other hand a vacuum demands to be filled and sucks to itself everything around it, like a vacuum cleaner. The invitation notes indicated that Cemeti was aware it had become an institution that was a focus of debate and they were sensitive to the criticism. The preamble to the invitation asked, “has this institution become hegemonic…. or is it opening the way for regeneration?” developed a community for contemporary art and an environment for information and debate.[50]Exhibition invitation, Cemeti Art House, emailed 17/08/03, preamble by Mella Jaarsma, Nindityo Adipurnomo

Few if any art galleries have survived in Indonesia as long as Cemeti or attempted as much. Few would deny the significant impact Cemeti has had on contemporary Indonesian art. Two practising artists provided an exhibition space for emerging artists of their generation where there was no other suitable space. They developed a community for contemporary art and an environment for information and debate. As Asmudjo Jono Irianto said of Cemeti,

“Hardly any other exhibition space in the country receives as much press coverage. News and reviews of its exhibitions are published not only in local publications, but also in national ones like Tempo weekly, Kompas daily and Gatra weekly. This is an indication that the exhibitions presented at the gallery are deemed ‘interesting’ or newsworthy, and their coverage has led both to the development of a nascent discourse and to an increased (though still limited) awareness of contemporary art in the minds of the general public.”[51]Asmudjo Jono Irianto, 2001, Outlet, ibid, p.75

Cemeti became a major outlet for showcasing Indonesian art internationally. It played a role in challenging colonial stereotypes not only by demonstrating the quality of Indonesian contemporary art but by contributing to the shift of art-world interest from European and American centres to Asia. They have fundamentally challenged the assumption that modern and contemporary art made in Indonesia is a poor copy of a Western original.

Cemeti began as a commercial gallery selling art works like commercial galleries anywhere else in the world but became an institution fulfilling functions provided elsewhere by government organisations, NGOs, art academies, even museums, for want of any alternative in Indonesia. Mella and Nindityo recognised the importance of documentation and promotion in the development of artistic careers and when this was beyond the capacity of the gallery, established the Cemeti Art Foundation. Together they became writers, curators, promoters, researchers, managers and educators at the same time developing their own artistic practice, and it is remarkable what they have achieved. But in this vacuum they became power brokers and herein lies the problem: this would not be an issue if there had been other alternative galleries and exhibition spaces of equal stature offering an outlet for work that Cemeti does not show. Although there are alternatives to the alternative gallery now, none have yet gained a similar international profile and power base, and many continue to fail.

There is a potential conflict of interest in the combination of artist and gallery owner, for Mella and Nindityo were in a position to promote their own work along with their stable of artists when international curators came to select Indonesian artists. Where Mella is concerned, this seems more opportune than intentional, as indicated when she was invited to exhibit in APT/3. The selection team was seeking female Indonesian artists and Mella said,

“I wasn’t thinking they were interested in my work, not at all actually, for I already had the idea that for all the international exhibitions they wanted a real Indonesian (female artist) because that’s what normally happens.”

Julie Ewington, curator of modern art at the Queensland Art Gallery and member of the Indonesian selection team for APT/3, asked to see images of her work so she showed her recent work from an exhibition in Japan and “… she was very enthusiastic”.

In a society that values non-confrontation and restraint, resentments bubble below the surface. Mella is accused of not being Indonesian and therefore should not represent Indonesia in international exhibitions. Mella was pleased to be presented as an Indonesian artist in APT /3, not in another section entitled, ‘Crossing Borders’, and she prefers that her work is seen as Indonesian. But her personal position, both in her work and in life, is cross- cultural. In the context of a globalised world, artists move across borders, encountering multiple cultural experiences and mixing with many artists, and it has created a form of art that has become dissociated from a single national identity and is to be judged by different criteria. This is not to deny local context but a non-Indonesian perspective conditions Mella’s perception of the Indonesian issues she addresses.

Mella also dismisses as envy the suggestion that Cemeti survived on money from the Netherlands:

“We are seen as successful gallery and they think a lot of money is coming from abroad, from my parents… which is not true I am a foreigner and they look at me as a new coloniser.”

Mella and Nindityo, though, had a head start on other organisations in raising funds for their projects from their contacts, particularly with organisations in the Netherlands. Nindityo was a graduate of the Rijksacademie, which has programs to support international projects and Mella obviously was familiar with Dutch cultural institutions and procedures.[52]Gridthiya Jaeb Gaweewong, “On Indonesian alternative spaces: a far perspective from Thailand”, in Cemeti Art House, 2003 ibid, p.106

Despite resentments remaining from the processes of independence, ex colonial states maintain many formal and informal contacts with their previous rulers: the relationship between the Netherlands and Indonesia being similar to that between the United Kingdom and the neighbouring post-colonial Malaysia. Cultural links are considered to facilitate economic and trade relations, as is often expressed in the statements of purpose by cultural organisations, such as Erasmushuis. The question arises as to whether Mella’s association with such organisations constitutes neo-colonialism.

Neo-colonialism is considered to be the economic manipulation of the emerging independent nation to the benefit of the ex-colonial power, but, according to Kwame Nkrumah, educational and cultural manipulation was more insidious and difficult to detect than the older overt colonialism.[53]Nkrumah, K., 1965, Neo-colonialism; the last stage of imperialism, London, Nelson The relationship between Cemeti, Mella and the ex-colonial power is more complex than this. Cemeti did not exploit the cultural resources of Indonesia by exporting them to the Netherlands, but Mella was born and raised in the ex colonial country and whether she intended it or not, she was accorded a respect similar to that given to colonial authority in the past. She had a knowledge/power base from her birth and education in the Netherlands that gave her influence and made her a gatekeeper. Mella’s activities facilitated her personal career and contributed to Dutch / Indonesian relations while at the same time being beneficial to contemporary Indonesian art and contributing to the international profile of Indonesian culture. A symbiotic relationship indeed.

Addendum:

In 2009 Mella and Nindityo declared a major change of direction for Cemeti Art House. Clearly their own exhibiting schedule had become extremely demanding and it was difficult for them to personally maintain the monthly exhibitions of the gallery and support art activities outside the gallery. Their website declared they would organize between two and six activities in the gallery each year which they referred to as ‘Art Practice and Society Projects’, offer residencies and hold workshops based on proposals.[54]Website: Cemeti Art House accessed 14/02/2012 As their own careers took off, particularly internationally, they were no longer attempting to support the gallery by sales from exhibitions and the gallery was becoming more of a non commercial centre for art related activities.

References

| ↑1 | Asmudjo Jono Irianto, “Cemeti Art House in the Indonesian Artworld”, in Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years Cemeti Art House : exploring vacuum, 1988-2003, Yogyakarta, Cemeti Art House, p.25 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Wicaksono, A., 2003 “Wawancara dengan Nindityo Adipurnomo dan Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti Dominan karena Sendirian”, Interview with Nindityo Adipurnomo and Mella Jaarsma, Cemeti, Dominant because it was alone, Yayasan Seni Cemeti, Aspek-Aspek Seni Visual Indonesia, Paradigma dan Pasar, Yogyakarta, Yayasan Seni Cemeti, p. 199. I have used this essay as a counter balance to personal interviews and conversations conducted with Mella and Nindityo between 2000 and 2005. It should be reported that Mella was not pleased with the Wicaksono interview. This was partly because the interviewer directed most questions to Nindityo, but also because she felt it was an expression of certain attitudes towards the gallery she considered the result of jealousy. There is a transparent awkwardness in the interview and it is clear Wicaksono was attempting to confirm a commonly held belief that Cemeti gallery held a powerful position, while Mella and Nindityo were resisting being defined, or defining themselves, as ‘hegemonic’. |

| ↑3 | Unless otherwise stated, all quotations and opinions expressed by Mella Jaarsma and Nindityo Adipurnomo are the result of conversations and interviews conducted in Yogyakarta June 2000, July 2001 and May 2002 and an interview held in Canberra, August 2003. |

| ↑4 | FX Harsono, 1997, Mella Jaarsma, Think it or not, exhibition catalogue, Yogyakarta Cemeti Gallery, p.15. Quotations are given as printed in the catalogue and can reflect a somewhat stilted translation from the original bahasa Indonesia. |

| ↑5 | Mella in conversation with FX Harsono, ibid., p.18 |

| ↑6 | Ibid., p. 22 |

| ↑7 | Interview, Mella Jaarsma, 28/06/00. The exhibition, Wearable Art, curated by Rifky Effendy and shown in Bandung, Yogyakarta and Ubud in 1999, exhibited a frog skin jilbab that was not full length. By the time the work was exhibited with three other jilbabs at APT/3, they were nearly floor length, covering everything but feet and eyes |

| ↑8 | Astri Wright, 1990 “Dancing towards Spirituality = Art”, in Nindityo Adipurnomo 1988 – 1990 Protection – Liberation – Expression, exhibition catalogue, p.3 |

| ↑9 | Astri Wright, 1990 catalogue essay, ibid., p.4 |

| ↑10 | Interview with Nindityo, Yogyakarta, 14/7/2001. The dissertation was by Clara Brakel and was titled, The Sacred Dances of the Kratons of Surakarta and Yogyakarta. See Enin Supriyanto, 1996 “The Burden of Javanese Exotica, The traditional aesthetic of Nindityo Adipurnomo”, in Art AsiaPacific, Vol. 3, No.4, p.90 |

| ↑11 | Saparinah Sadli, “Feminism in Indonesia in an International Context”, in Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, eds., Women in Indonesia, Gender, Equity and Development, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2002, p. 85. Saparinah Sadli discusses the debate that occurred in ‘The Stepping Stones Project’, 1995, part of Kajian Wanita, the Graduate Women’s Studies Project at the University of Indonesia, or UI. |

| ↑12 | Sylvia Tiwon, “Models and Maniacs, Articulating the Female in Indonesia”, in Laurie J. Sears, ed., Fantasizing the Feminine in Indonesia, Duke University press, 1996, p.54 |

| ↑13 | Mikke Susanto, “Pigura dan sejarah tersumbunyi”, The Frame and Hidden History, in Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years exploring vacuum, ibid, p.67 |

| ↑14 | Enin Supriyanto, 1996, ibid, p.92 |

| ↑15 | The rupiah was stronger then: according to Mella, in 1988 Rp90, 000 = AUD$60. In 2003 Rp90, 000 = AUD$16 |

| ↑16 | Wicaksono, A., 2003 ibid, p.192 |

| ↑17 | Ibid, p.192 |

| ↑18 | Ibid., p.195 |

| ↑19 | In May 2007 the Cemeti Art House website declared their supporters as Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development, Kelola – Yayasan untuk Seni Budaya, Artoteek den haag, Cultural & Development Indonesian Embassy Netherlands and the Ford Foundation; but in June the website was up dated and the list was removed. The new website can be found at: Cemeti Art House |

| ↑20 | www.erasmushuis.or.id see ‘Advisors’ accessed 02/09/03 |

| ↑21 | These comments were made in a group discussion, Bandung, 04/07/2001, one local curator saying that Tisna Sanjaya would be the only Bandung artist to be exhibited at Cemeti. This was somewhat refuted by the fact that the current exhibition at Cemeti at the time was a young Bandung artist, Gusbalian; but the perception remained |

| ↑22 | Cemeti Art Foundation is now the Indonesian Visual Art Archive and the website that recorded this comment no longer exists |

| ↑23 | Jim Supangkat, 1995, “Knowing and understanding the differences’, in Orientation, catalogue, Gate Foundation, p.46 |

| ↑24 | Carla Bianpoen, in her article for the Jakarta Post, 24 August, 1995, points out that although there were an equal number of artists participating from Indonesia and the Netherlands, the balance slipped when it came to the curators. Jim Supangkat was identified as the only Indonesian curator in a team of 6, the other two curators for Indonesia were identified as Esther de Charon de Saint Germain and Mella, the latter, apparently, was not considered Indonesian. |

| ↑25 | Esther de Charon de Saint Germain, Interview with Nindityo Adipurnomo, 1993, Orientation catalogue, 1995, ibid, pp 50-52 |

| ↑26 | Interview, Anusapati, Yogyakarta, 13/05/05 |

| ↑27 | Kim Knopprs, 2003, Morbus Sacer, (Holy Desease), exhibition catalogue, Netherlands, provided courtesy of Erzsebet Baerveldt and translated by Dieneke Carruthers |

| ↑28 | M. Dwi Marianto, 1996 “Cultural Orientations, Art from the Netherlands and Indonesia”, Art AsiaPacific, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp.38-39 |

| ↑29 | The first two properties were rented, but as of 2011, the IVAA address is understood to be owned by the foundation and is listed on their website as: Jalan Ireda Gang Hiperkes MG I-188 A/B, Kampung Dipowinatan, Keparakan, Yogyakarta 5515 |

| ↑30 | www.hivos.nl accessed 28/05/03 |

| ↑31 | AWAS! and Cemeti’s involvement in political art is discussed in more detail in the chapter on Reformasi |

| ↑32 | See:”An Overview on AsuRA & G-Project of Cemeti Art Foundation”, 2006. This report was provided by Aisyah Hilal, director of CAF at the time and a recipient of an Asialink /Kelola residency in Australia to study art education. Further information was provided in emails, 16/03/06 and 20/03/06 |

| ↑33 | This opinion was expressed by Asmudjo Jono Irianto, 2001, “Tradition and the Socio-political Context in Contemporary Yogyakartan Art of the 1990s”, in Outlet, Yogyakarta within the Contemporary Art Scene, Yogyakarta, Cemeti Art Foundation, p.74 |

| ↑34 | Wicaksono, A., 2003 ibid. |

| ↑35 | Interview, Tisna Sanjaya in his home, Bandung, 04/07/01 |

| ↑36 | Dwi Marianto, 1995, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, PhD thesis; unpublished, University of Wollongong, p.52 and p.163 |

| ↑37 | Interview Enin Supriyanto, 02/09/09. The term, ‘surrealism’ is more commonly used than ‘neo mysticism’ but due to debate concerning the relationship between Yogyakartan surrealism and European Surrealism, the capitalization of surrealism is avoided here. |

| ↑38 | Exhibition schedule at Cemeti Gallery 1988 – 2002 in Cemeti Art House 2003, 15 years exploring vacuum, ibid, pp. 244-247 |

| ↑39 | Galeri Lontar, in Jakarta, the only other gallery to maintain records at the time, indicated a similar low ratio of female to male artists in their exhibition list. Statistics have proved difficult to obtain and the proportion of female students in the art academies, for example, is based on the estimates of teachers, although overtures for information were made to the relevant administrations. Dwi Marianto stated that “In the Fine Arts Department of the Indonesia Art Institute of Yogyakarta (ISI)….the number of female students is less than five percent of the male.” M. Dwi Marianto, “Recognising new pillars in the Indonesian Art World”, Text and Subtext, exhibition catalogue, Earl Lu Gallery, Singapore 2000, p.139. When asked how he had obtained these figures, Dwi said that he had made a head count of his female students, interview, 28/05/02. Female participation in the art academy courses is believed to be increasing but again this is opinion lacking statistics. |

| ↑40 | Saparinah Sadli, “Feminism in Indonesia in an International Context”, Kathryn Robinson and Sharon Bessell, eds., 2002, Women in Indonesia, Gender, Equity and Development, Singapore, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 80 |

| ↑41 | See Reilly, M. and Nochlin, L., eds, 2007, Global Feminisms, new directions in contemporary art, Merrell, London and New York and The Brooklyn Museum. Astri Wright was one of the few writers previously to identify Indonesian women artists with a chapter in her book. Her focus was on the careers in the manner of recovery projects, rather than the causes. See Astri Wright, 1994, Soul, spirit, and mountain: preoccupations of contemporary Indonesian painters, Kuala Lumpur, Oxford University Press, Chapter 6 |

| ↑42 | Interview, Goenawan Mohamad, May 17th, 2002 |

| ↑43 | Bianpoen, Carla, Wardani, Farah and Dirgantoro, Wulan, 2007, Indonesian Women Artists, The curtain opens, Jakarta, Yayasan Seni Rupa Indonesia, p.27 |

| ↑44 | The frogskin jilbab became one of four pieces shown by Mella Jaarsma in the Asia-Pacific Triennial in 1999 titled, Hi Inlander (hello native), and subsequently purchased by the Queensland Art Gallery. |

| ↑45 | See Mella’s website: Mella Jaarsma accessed 9/02/2012 and the catalogue of her exhibition, The Fitting Room, Galeri Nasional, Jakarta, 27 October – 8 November, Selasar Sunaryo Art Space, Bandung, 14 November – 6 December, 2009, Selasar Sunaryo Art Space. |

| ↑46 | Various writers describe the development of such influences, including Emmerson Donald K., 1999, Indonesia beyond Suharto : polity, economy, society, transition, Armonk, N.Y., M.E. Sharpe, pp.285 – 288, and Adrian Vickers who describes the culture of the shopping malls, in Vickers, A., 2005, A history of modern Indonesia, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, pp.198-199 |

| ↑47 | Exhibition invitation titled in Dutch, Lekker Eten Zonder Betalen, Tasty Meal Without Paying, 16 participants, March 2-30, 2003, Cemeti Art House, email, 26/02/03 |

| ↑48 | Cemeti Art House, 2003, 15 years exploring vacuum, ibid, ‘Anecdotes’, p.7 |

| ↑49 | Christine Clark, “Distinctive Voices: Artist – initiated spaces and projects” in Turner, C., ed., 2005 Art and Social Change Contemporary Art in Asia and the Pacific, Canberra, ACT, Pandanus Books, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, ANU, p.557 |

| ↑50 | Exhibition invitation, Cemeti Art House, emailed 17/08/03, preamble by Mella Jaarsma, Nindityo Adipurnomo |

| ↑51 | Asmudjo Jono Irianto, 2001, Outlet, ibid, p.75 |

| ↑52 | Gridthiya Jaeb Gaweewong, “On Indonesian alternative spaces: a far perspective from Thailand”, in Cemeti Art House, 2003 ibid, p.106 |

| ↑53 | Nkrumah, K., 1965, Neo-colonialism; the last stage of imperialism, London, Nelson |

| ↑54 | Website: Cemeti Art House accessed 14/02/2012 |